ARTS

This is London's silly season for dance, with more events to see than there are nights in the week. Sadler's Wells Royal Ballet has been showing two programmes featuring new works by three young dan- cers turned choreographers. Graham Lus- tig's Paramour wasn't helped by the fact that it preceded a triple bill of early Ashton ballets: Valses nobles et sentimentales, Cap- rio! Suite and Façade. Ashton refers to these as his 'minutiae' but all are examples of the finest craftsmanship already im- printed with his personal style.

Paramour, though well constructed and sustained, comes across as a light cocktail of influences (Les Biches and Manon in particular) without discernible individual- ity. It is far too similar in theme to Valses nobles to benefit from being placed right next to it. Ashton's gathering of adoles- cents at a ball is a little masterpiece of obliquity, with rivalries just hinted at in glances or in the way the ballerina, Marion Tait, is wafted in supported fetes between one partner and another. Lustig's ball, a more frivolous, urbane occasion reflecting the mood and period of Poulenc's Concer- to for Two Pianos, seemed crudely drama- tic by comparison, with Tait tugged be- tween David Yow and Petter Jacobsson. Paramour is elegantly designed by Nadine Baylis, whose evocation of 1930s Paris would have had greater effect if Lustig had managed to instil in his dancers more of an understanding of Biches-style chic.

Private City by Susan Crow was inspired by the poems of A. S. J. Tessimond — one of those writers whom people have heard of but probably not read. Crow reproduces the poet's vignettes of urban types with her trio of clownish drunks, a neurotic woman and a couple whose self-absorption is eloquently expressed in an inwardly melt- ing duet. Tim Shortall's simple geometric set effectively suggests a modern city- scape, though there was something ungain- ly about his costumes tailored in see- through plastic. The score by John Surman heightens the sense of yearning implicit in the piece with its plaintive saxophone and clarinet improvisations (played by the com- poser) contrasted against a background of synthesised texture such as traffic noises. Private City begins much as Jerome Rob- bins's Glass Pieces does, with the cast set in motion as implacable clockwork pedes- trians, and the dance only really gets going halfway through. Crow is capable of choreographing with admirable fluency, but the ballet as a whole leaves you uncertain of just what she is trying to say.

Derek Deane's The Picture of Dorian Gray is a merciless exposé of dance's limitations. Nicholas Millington's ardent

Dance

The Royal Ballet (Royal Opera House) Dance Umbrella (Riverside Studios and other venues)

Ballet's bumper crop

Julie Kavanagh

solo as Basil Hallward can say, 'He's beautiful and I'm infatuated,' but hardly that Dorian's personality has suggested to him an entirely new manner in art. Nor can the rest of the ballet take on the novel's indictment of contemporary aestheticism — its whole raison d'être. So Dorian Gray becomes just a pretty catamite, whose ruthless rejection of Sybil Vane seems to be motivated more by snobbery than by a sense of betrayal at her valuing life above art.

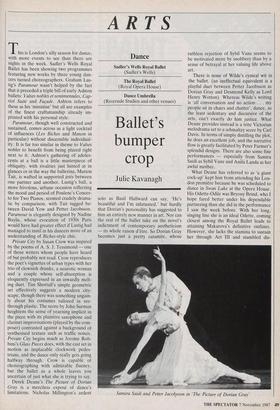

There is none of Wilde's cynical wit in the ballet. (an ineffectual equivalent is a playful duet between Petter Jacobsson as Dorian Gray and Desmond Kelly as Lord Henry Wotton). Whereas Wilde's writing is 'all conversation and no action . . . my people sit in chairs and chatter', dance, as the least sedentary and discursive of the arts, can't exactly do him justice. What Deane provides instead is a trite Victorian melodrama set to a schmaltzy score by Carl Davis. In terms of simply distilling the plot, he does an excellent job, and the narrative flow is greatly facilitated by Peter Farmer's splendid designs. There are also some fine performances — especially from Samira Saidi as Sybil Vane and Anita Landa as her awful mother.

What Deane has referred to as 'a giant cock-up' kept him from attending his Lon- don premiere because he was scheduled to dance in Swan Lake at the Opera House. His Odette-Odile was Bryony Brind, who I hope fared better under his dependable partnering than she did in the performance I saw the week before. With her long, singing line she is an ideal Odette, coming closest among the Royal Ballet leads to attaining Makarova's definitive outlines. However, she lacks the stamina to sustain her through Act III and stumbled dis-

Samira Saidi and Petter Jacobsson in 'The Picture of Dorian Gray' quietingly out of her uncompleted fouette sequence.

When I saw Maria Almeida's interpreta- tion I began to think it might be an idea to go back to the days of having two dancers share the ballerina role. Almeida's Odette is too angular and her arms flap rather than flow and ripple — she is more like the Bluebird's Enchanted Princess than a swan — but her Qdile is triumphant. Almeida is proving to be the company's much needed classical technician whose dancing has dul- cet finesse. Her debut as the Firebird was a model of clarity but lacked command. Again, her arms require greater weight of expression and she could use her beauti- ful eyes to far more bewitching effect.

The Stravinsky triple bill of The Fire- bird, Scenes de Ballet and The Rite of Spring under Bernard Haitink's inspired conducting attracted hordes of music afi- cionados whom one, recognised from opera performances and the Glyndebourne train. The exemplary standards in the pit infected the dancers, who performed with more intensity and crisper control than we've seen for some time. In her debut as the Chosen Maiden, Fiona Chadwick intro- duced a Petrushka-like poignancy to the dance that I hadn't noticed before. And reinventing the role as the first male interpreter (the Chosen One), Simon Rice, while no less affecting, seemed to give more conventional shape to the convulsive movements.

Stephen Petronio — one of Dance Umbrella's star imports from New York exploits a similarly primitivist abandon in his dancing and choreography. To the tribal beat of David Linton's commissioned scores, he and his five dancers let rip on stage with hectic runs, flung-away fetes and windmilling arms, occasionally reining themselves in to perform in slow-motion unison. With his quirky, contortionist's dislocation of the body, Petronio's dancing appears entirely original, but .in fact it's an eclectic accumulation of styles ranging from ballet to go-go and breakdancing. The programme, which began with an engrossing on-spot solo by Petronio, was immensely enjoyable, even though I felt that Simulacrum Reels and Walk-In, des- pite their different designs, could be one and the same piece.

I always equate a Dance Umbrella sea- son with an element of suffering, and the prize for this year's most sadistic partici- pant must surely go to Ashley Page. The music for The Angel of Death is in My Bed Tonight by This Heat is like an unremitting scream amplified beyond endurance (apparently by the musicians themselves who are now obviously incapable of nor- mal hearing). And like the hanging mobile of flotsam the choreography looks random and incohesive, deliberately perhaps, but taxing all the same. Page is extremely gifted at revamping classical steps with maverick distortions as well as eliciting unseen strengths from his rigidly Royal Ballet-trained cast (launching corps de ballet dancer Kathryn Dunn, for example, in the role of a svelte siren). However, there is such an overkill of material in this piece — of both dance and narrative effects — that after an hour I had seen more than enough. The point of Dance Umbrella is to license experimentation, but there is a very narrow line between that and all-out in- dulgence.

Previous page

Previous page