ARTS

Exhibitions

Cezanne (Grand Palais, Paris till 7 January, Tate Gallery from 8 February till 28 April Philadelphia Museum of Art from 25 May till 18 August)

Cry of Cezannah!

Cezannah!

Martin Gayford sings the praises of Matisse's Good God Cezanne, Matisse used to say, was a sort of god of painting. High praise, and from an authoritative source. This eulogy, moreover, could have been — and indeed, is — echoed by many others. Henry Moore remembered seeing a collection of Cezannes in Paris in 1922, 'For me this was like seeing Chartres Cathedral' Thus the art of the 20th century really was in many ways inaugurated with a loud cry of `Cezan- nah! Cezannahr — as sceptics used to par- ody the message of the critic Roger Fry. This alone would make the retrospective exhibition which has just opened at the Grand Palais, Paris — and which moves next spring to the Tate — an event of the first importance in the world of art.

It is more than that. Following the art of Cezanne as it unfolds decade by decade is an immensely powerful and enjoyable experience. There have, of course, been plenty of other Cezanne exhibitions, mainly thematic ones of late. But this is the first major retrospective since 1936 which simply follows the development of Cezanne's art: from entirely conventional academic nudes in the 1860s to the last paintings left unfinished at his death in 1906.

There are exhibitions of which a review, in the normal sense, is preposterous. They are too massive, too rich, too laden with great masterpieces for it to be seemly or possible for the critic to pen more than an earnest exhortation: go to it, and go as often as you can. One such was the Poussin show at the Royal Academy last spring. This is another.

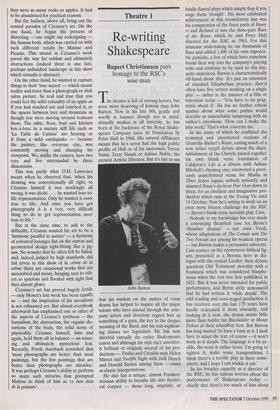

There is an enormous amount to look at in blockbusters of this kind, a wealth that Nature Morte au Punier c. 1888-90, by Cezanne can seem overwhelming. But there are also things that only blockbusters can show. In this case, for example, the juxtaposition of naked 'Bathers' of various periods; a whole wall of paintings of the Montague Sainte- Victoire from the 1880s, the view changing as if seen from a train window, and more from the 1900s. There is a symphonic sense of the development and variation of the major themes: still lifes, landscapes, portraits.

It is an unfailingly enthralling sequence, all the more so because, in one sense, it is highly repetitious. One sees Cezanne's treatment of apples, or the mountain, or the face of his wife, unfold before one's eyes. At the end of the last room are three of the final paintings of bathers, including the familiar one from the National Gallery, and — upstaging it entirely — a huge one from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Looking at this, one understands the force of Moore's remark about Chartres. The whole design is put together with the architectural inevitability of a Gothic portal (just as the planes, and arcs and general blocky solidity of still lifes and landscapes can remind one of the Romanesque buildings of Provence).

In this last 'Grandes Baigneuses' there are arching trees on either side, and monu- mental groups of female nudes arranged beneath and between — strange ungainly, massive creatures, from whom are descend- ed the women of Picasso, Matisse and the vast maternal figures of Moore. Cezanne himself had been toying with them for decades, several of the very same figures turn up in paintings of bathers from 20 years before, exhibited close to the beginning of the show (of which, unsurprisingly, one was owned by Picasso, one by Matisse, one by Moore). These inventions of Cezanne's have fed many other succeeding artists — looking at the 'Cum Baigneuses' of 1885, for instance, one is immediately reminded of Balthus, one of the greatest living figurative painters.

But where did Marine get the ideas for these weird creatures — these distorted, mangled women, as R.B. Kitaj put it, with 'no ankles and webbed feet'? One might speculate on their psychological roots in the mind of a painter who had a neurotic horror of physical contact, and had painted in his youth violent and "erotic fantasies of fevered voluptuousness. Then there was the difficulty of finding suitable models in 19th-century Aix-en-Provence. His famous project of 'redoing Poussin over again, according to nature' meant posing a group of nudes like a classical Poussin in the open air, and sitting down to paint them as if they were so many rocks or apples. It had to be abandoned for practical reasons.

But the bathers, above all, bring out the central paradox of Cezanne's art. On the one hand, he began the process of distorting — one might say redesigning — the human body, which was carried on with such different results by Matisse and Picasso. This strand in Cezanne's work paved the way for cubism and ultimately abstractions (indeed there is one late, perhaps unfinished landscape in this show which virtually is abstract).

On the other hand, he wanted to capture things in their 'true aspect' — which meant realler and truer than a photograph or slick salon picture. So real and true that you could feel the solid rotundity of an apple as if you had reached out and touched it, or the spaces between tree and mountain as though you were moving around between them. The table, floor, fruit and kitchen bric-a-brac in a mature still life such as 'La Table de Cuisine' are heaving as if from a mild earthquake — because the painter, like everyone else, was constantly moving and changing his viewpoint. We, unlike the camera, have two eyes and live surrounded by three dimensions.

This was partly what D.H. Lawrence meant when he observed that, 'when his drawing was conventionally all right, to Cezanne himself it was mockingly all wrong, it was cliché . . . he wanted true-to- life representation. Only he wanted it more true to life. And once you have got photography it is a very, very difficult thing to do to get representation more true to life.'

But at the same time, to add to the difficulty, Cezanne wanted his art to be a 'harmony parallel to nature' — a harmony of coloured lozenges flat on the canvas and geometrical design tight-fitting like a jig- saw. No wonder that he often felt he failed, and, indeed, judged by high standards, did fail (even in this show of la creme de la creme there are occasional works that are unresolved and messy, hanging next to oth- ers so spacious and flooded with light that they almost glow).

Cezanne's art has proved hugely fertile — only Monet's late work has been equally so — and the inspiration of his inventions is not exhausted yet. But almost everybody afterwards has emphasised one or other of the aspects of Cezanne's synthesis — the formalism, the abstraction, the organic dis- tortions of the body, the solid sense of physicality. Cezanne himself, time and again, held them all in balance — an amaz- ing and ultimately mysterious feat. Recently, Frank Auerbach remarked that 'most photographs are better than most paintings, but the few paintings that are better than photographs are miracles.' It was perhaps Cezanne's ability to perform so many such miracles that prompted Matisse to think of him as `ce bon dieu de la peinture'.

Previous page

Previous page