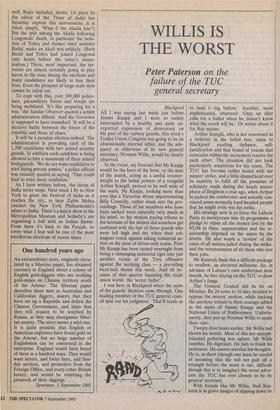

RAJIV OPTS FOR HAVOC

Dhiren Bhagat predicts

violence during the Punjab elections this month

Bombay IN CASE you've already forgotten Nellie an article in last month's Gentleman, Bom- bay's imitation Esquire, will remind you of the massacre. It is an account of a recent visit to the scene of the worst carnage that took place during the Assam elections in February 1983. At the head of the article appears a photograph of a young girl standing in a field, looking sullen and slightly bewildered. At her feet rest weath- erbeaten skulls. The caption reads: 'Nel- lie's mass graves still exist.'

The caste Hindu agitators in Assam didn't want elections to be held without a revision of the electoral rolls which they (rightly) pointed out were stuffed with the names of Bangladeshis who had illegally migrated to India. Mrs Gandhi went ahead and finally announced the elections early in January. The agitators' anti-election post- ers showed the massive Assam rhino charg- ing, its ridiculously small eyes set with manic determination, its single wild horn intent. The threat was clear enough: vegetarian that he is, the rhino charges intending only to defend, but his charge can easily prove fatal.

What happened went way beyond de- fence. The agitators called for a state-wide boycott of the elections. Nellie, a cluster of villages largely populated by Muslims, wasn't prepared to obey. The villagers voted for the 'hand', the Congress symbol. Two days later, on 18 February, they were surrounded by a crowd armed with spears, swords, guns and axes. The massacre lasted all day. According to the govern- ment, 1,383 villagers were killed, but government figures are notoriously low: others say 3,000, the article in Gentleman puts the figure at 5,000.

Of course Nellie hasn't forgotten so quickly, but it appears most of India has. (A joke doing the rounds in the central hall of Parliament picks on this national prop- ensity: 'Knock, knock.' Who's there? 'In- dira.' Indira who? 'Have you forgotten so soon?') Appearing as it did, in the month the peace accord in Assam was signed and bygones began to look more and more like bygone, the article was well timed. For it is not at all clear that the lessons of Nellie have been learnt.

Just after Nellie it became fashionable to condemn the government for going ahead with the Assam elections, but at the time the elections were announced most of the national press supported the government's stand. . . The Union Government can- not and should not drop the elections in Assam. . . New Delhi must press ahead with the poll even if it has to be under the shadow of the army's bayonets,' pro- nounced the Times of India on 5 February. On 11 February, after 51 deaths, the Times changed its mind. The radical Indian Ex- press was less brash but equally firm: 'Now that an election is under way it would be imprudent to call it off(3 February). The Express changed its mind on 15 February, when the death toll stood at 272.

On 19 January the Delhi Hindustan Times was clear about what had to be done: 'The Prime Minister and the Chief Election Commissioner have rightly turned down the Opposition's pleas to postpone the Assam "elections".' Eleven days later the paper changed its mind. Neither the Calcutta Statesman nor the Madras Hindu bothered to do an editorial switch. And the Calcutta Telegraph, which mostly took a confused line, expressed the liberal intel- lectual's position clearly on 25 January: `What is now at stake is the integrity of the country and the constitutional system. The cost of going back from the the elections at this stage would be much higher than holding the elections.'

There were no more than three com- mentators in the national press who thought the elections should be called off. I was one of them. I had just spent a few weeks in Assam and wrote in the Sunday Observer (23 January) of the folly of holding the elections. The constitution would not permit President's rule in Assam for much longer and as many had pointed out, there was no time left to amend the constitution. I had therefore written that even if the government had to violate the constitution by calling off the elections it should do so in view of the imminent danger. The assistant editor who handled my copy struck that paragraph out. When I came in to read the proofs I spotted this and protested. 'I'm sorry,' she said, 'this is a responsible paper: we cannot tell the government to violate the constitution.' I tried arguing but it was of no use, she was a `sensible' lady, a long-time critic of the government with a serious interest in civil liberties.

Now that the Punjab elections are upon us, people in the streets are debating whether or not Rajiv should go ahead with the electoral exercise, especially after the assassination of the moderate leader Sant Longowal. A few days ago I ran into the same assistant editor in the Sunday Obser- ver office. As our conversation turned to the Punjab elections I reminded her of the cut she had made. 'How long ago that seems now,' she said ruefully, 'in those days we cared about things like "constitu- tionality and "democratic provesses". So much has happened since then.' She laughed an uncertain laugh. 'Now we're just concerned about security, that people shouldn't die.'

A lot has happened. True, there was a predictable fuss in the press when Rajiv said — at this first press conference two months ago — that he wouldn't hesitate to impose another emergency should the situation merit one, but it's more remark- able how many people today want another national emergency. In June, to mark the tenth anniversary of the imposition of Mrs Gandhi's emergency, the magazine Imprint commissioned a survey in the four big cities, Delhi, Calcutta, Bombay, Madras. Sixty-seven per cent of the sample thought the 1975-7 emergency had been a good thing for the country and 65 per cent said they would support another emergency. (Delhi, which has borne the brunt of the recent terrorism, has 84 per cent of its respondents saying they would support another emergency and only eight per cent saying they would oppose it.) It's hardly surprising then that a lot of people have come out against the Punjab poll. After the peace accord was signed on 24 July even Sant Longowal sent a message to the Prime Minister saying he would prefer the poll to be delayed till February.' But Rajiv went ahead and announced the elections. Longowal was busy putting together a united party when he was killed on 20 August. In response Rajiv delayed the poll, but only by three days, to 25 September.

There are two good reasons for going ahead with the poll. One, Rajiv does not want to let the terrorists dictate to him. Two, the commissions of enquiry that the accord set up are time bound. And once their recommendations are implemented the bickering will begin again and the goodwill of the accord will run out.

But there are better reasons for postpon- ing the poll and for declaring a state of emergency in the Punjab. Sant Longowal had wanted a few more months so that he could cement Hindu-Sikh relations. Now that he is no more it is even likelier that an election — with all its rancour — will worsen the relationship between the two communities. Two, there was a good chance that the Akalis under Longowal would have won enough seats to form a government, a result all who wish the state well, Rajiv included, desire. (A piece by the editor of the Times of India last Saturday express this nervousness: it is titled, simply, 'What if the Akalis lose?) But the split among the Akalis following Longowals' death, in particular the isola- tion of Tohra and former chief minister Badal, make an Akali win unlikely. (Both Badal and Tohra had joined Longowal only hours before the latter's assass- ination.) Three, most important, the ter- rorists are almost certainly going to play havoc in the state during the elections and many candidates are likely to lose their lives. Even the prospect of large-scale riots cannot be ruled out.

To cope with this, over 100,000 police- men, paramilitary forces and troops are being mobilised. 'It's like preparing for a war,' the Sunday Observer quoted a senior administration official. And the Governor is supposed to have remarked: 'It will be a decisive battle between the forces of the republic and those of chaos.'

It will be a peculiar election indeed. The administration is providing each of the 1,200 candidates with two armed security guards. In addition each candidate is being allowed to hire a maximum of three armed bodyguards. 'We do not want candidates to start hiring private armies,' a police official was recently quoted as saying. 'That could lead to even more confusion.'

As I have written before, the circus of India never stops. Next week I fly to New York to greet the Festival of India as it reaches the city, to hear Zubin Mehta conduct the New York Philharmonic's salute to India. There's a major show at the Metropolitan Museum and Sotheby's are organising a ball with an Indian theme. From there it's back to the Punjab, to cover what I fear will be one of the most murderous elections of recent times.

Previous page

Previous page