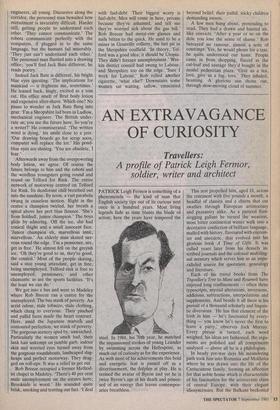

AN EXTRAVAGANCE OF CURIOSITY

Travellers: A profile of Patrick Leigh Fermor, soldier, writer and architect

PATRICK Leigh Fermor is something of a phenomendn — the kind of man that English society tips out of its curious nest once in a hundred years. Most living legends fade as time blunts the blade of action; here the years have tempered the steel. In 1984, his 70th year, he matched the impassioned strokes of young Leander by swimming across the Hellespont, as much out of curiosity as for the experience. As with most of his achievements this bold and energetic feat is passed off as a divertissement, the dolphin at play. He is termed the avatar of Byron and yet he is twice Byron's age at his death and posses- sed of an energy that leaves contempor- aries breathless. This zest propelled him, aged 18, across the continent with five pounds a month, a headful of classics and a charm that cut swathes through European artistocracy and peasantry alike. As a putteed foot- slogging gallant he turned the weariest, most bitter continental winter walk into a decorative confection of brilliant language, mulled with history, flavoured with encoun- ter and anecdote, that evolved into his glorious book A Time of Gifts. It was culled years later from his densely in- scribed journals and the colossal multiling- ual memory which serves him as an unpa- ralleled source for quotation, genealogy and literature.

Each of his travel books from The Traveller's Tree to Mani and Roumeli have enjoyed long confinements -- often three typescripts, myriad alterations, inversions, additions, subtractions, interpolations and supplements. And beside it all there is his pursuit of a thousand scholarly and linguis- tic diversions. 'He has that element of the Irish in him — he's fascinated by every- thing — you know he's never the first to leave a party,' observes Jock Murray. Every phrase is turned, each word weighed, his ideas are fashioned, the argu- ments are polished and all components analysed — above all he is a philologian.

In heady pre-war days his meandering path took him into Romania and Moldavia where he was drawn into the life of the Cantacuzene family, forming an affection for that noble house which is characteristic of his fascination for the aristocratic clans of central Europe, with their elegant idiosyncrasies. But the Balkans beckoned and the Pindus and Rhodope mountains lured him east and south so that by the age of 20 he was riding with the Greek cavalry during a rebellion, and five years later he was in Albania with a future Greek prime minister, Kanellopoulos, as a comrade-in- arms, pushing back the Italian army.

That taste of Greece and the Greeks at war sowed the seeds of his philhellenic passion — later he ran the resistance movement in German-occupied Crete, gilding his extraordinary career as a Guards officer by capturing and evacuating to Cairo the German commander, General Kreipe, in 1944. That episode earned him a DSO as well as becoming the subject of Stanley Moss's book, and later film, Ill Met by Moonlight. Other frequent chilling en- counters with the Germans in the White Mountains and the adventurous spirit amongst the SOE fraternity in Cairo cre- ated a lasting camaraderie, above all with author, traveller and colleague Xan Field- ing, who detailed their harrowing life in Hide and Seek.

The post-war years saw the fulfilment of delayed pleasure. Carousing vied with con- versation, and the nightlife of artistic cafés filled the early hours across Europe from the Athens of Katsimbalis and Seferis to the Paris of Diana Cooper and the London of Philip Toynbee, Ann Fleming and Andrew Cavendish, now Duke of Devon- shire. This appetite for society played havoc with creative production sometimes, for instance during their sojourn in Poros, as the artist John Craxton records, where the daylight hours seemed too brief for his painting and the night time too abbreviated for Paddy's writing. Paddy occasionally dived into monastic retreat, from the deep peace of which he drew his book A Time to Keep Silence.

But stronger and more lasting intoxica- tion than the ouzo at the British Institute in Athens came in the renewed acquaintance he made with Joan Eyres Monsell who became companion, wife and the steadying hand on the tiller of his fast barque. 'She has given a line to his life — the discipline he needed sometimes.' She has had to manoeuvre him away from the ceaseless crowds that cross their threshold for an hour of conversation with the man whose writing has been called 'the despair of all future autobiographers' by C. M. Wood- house.

Throughout Greece he is a celebrated figure and the draughts of retsina that have been sunk to confirm that country's wel- come to him are unnumbered. That some unseen political enemy blew up his car causing him no injury fortunately — mere- ly reinforces the impact he has had on Greeks.

In company he is a firework, colourful, flamboyant and dazzling. A dinner party in his presence is hardly complete if his companions are not regaled with recita- tions of Homeric Greek, the Eton Boating Song in Hebrew or the folk songs of Cretan bandits, and these are the merest tincture of his melodic and folkloric range. The artist Ghika records him singing wildly in New York, Lawrence Durrell describes him entrancing Cypriot peasants with his tunes, Peter Quennell reports Paddy leap- ing from rock to rock chanting wild Greek songs and Rudolf Fischer admits to cor- recting the odd word in the lyrics of Paddy's remembered Hungarian gypsy songs. Then there are Romanian couplets, Sarakatsan odes, French calypsos, Grego- rian chants and opera, all expressed with the genial ebullience of a buffo operatic star whose voice is wrought with laughter, and whose face is cast with smiles.

One of Paddy's companions during arduous mountain treks, Renee Fedden, describes how 'he turned every evening during our expeditions into a cocktail party. We would all be exhausted, weary from the day's journey and as soon as we were in the tent the evening would be transformed into a celebration.' On a trip to the Andes, Paddy describes his role as that of tending the primus stove but from that he evolves into jester and storyteller as well as an acute diarist. His enthusiasms sometimes lead to the most enjoyable explosions in the starchiest of places. Once aboard the Niarchos yacht at dinner, a premier cru, a great classic vintage claret, pre-phylloxera, was being poured out by white-coated waiters with infinite caution for the sacred nectar. Paddy having sensed its nose, eyed its colour and allowed the precious wine to caress his palate cried out: `Let's have beakers of this wine!' as the stunned fellow diners took on the features usually seen in an H. E. Bateman carica- ture.

An occasion he now savours with wry reflection was when he was invited to stay with Somerset Maugham after winning the Heinemann Foundation Prize for Litera- ture. He arrived loaded with luggage, expecting a pleasant stay. Feeling surpri- singly unequal to the task of managing dinner on the first evening he fortified himself with a couple of drinks before meeting the Master. As the meal progres- sed more wine flowed and inhibition gave way until Paddy told a malapropos story about the College of Heralds, the enact- ment of which required the imitation of a stutter. Maugham's Achilles heel had been touched. Towards midnight he profferred Paddy a cup of coffee; stirring it lightly, he bent towards him and said: 'I'll wish you good night, Mr Leigh Fermor, and good- bye — since you'll be gone by the time I get up in the morning.' Thus dismissed, Paddy hauled off his weighty baggage to a nearby hotel.

Paddy enjoys a global knowledge of architectural styles and the personal design and construction of his home in the Pelo- ponnese reflects much of his character. On a rocky promontory amidst patrician cyp- ress trees and dark olives, above the sea and set in a delightful terraced garden stands a substantial house. Roman villa, Pelion manor house, Pasha's summer resi- dence — the house defies classification. 'It highlights so much of Paddy — the refine- ment, the timbered detail, the shady arcades, the geometric pebbled mosaic it merges with the landscape,' John Crax- ton says. To Ghika, its essence is Hellenis- tic, with fractured local masonry inserted into stone walls giving the place an air of history and completing an architectural delight.

Here, and earlier on Hydra, constella- tions of literary figures have gathered to imbibe the spirit and catch the warmth of the intellectual fire which emanates from his inquiring mind.

The Duke of Devonshire notes the comfort of the villa and reports with pleasure how each meal is eaten at a different part of the house or garden. This migration is geared to defeat the blinding heat of the Messenian sun and allows for the maximum consolation of seasonal breezes and shade. From his writer's sanc- tum, a pavilion separate from the main house, he composes his long letters. Here he creates an almost annual greeting to his correspondents in the form of a special oeuvre — translations of German poetry or the latest travelogue of his ventures into Peru, the Pindus or Himalayan peaks. Here too he has mulled over the language of the Quecha Indians and the bizarre speech of the Malani in their remote Indo-Himalayan outpost.

Paddy's strength — the extravagance of his curiosity — leads to a density of style, saturated with references and rich lan- guage; as one acquaintance says, he does `overcharge his rifts with ore — but such ore!' Another friend describes Paddy at Chatsworth devising joke titles for those library doors masquerading as book- shelves. Peter Quennell singles Paddy out as a most intrepid horseman. 'He once asked to be put up on a hunter and insisted on trying every jump at the Towcester races. His hostess Kisty Hesketh watched him through fieldglasses crashing through the jumps and falling off, remounting and continuing the whole way round. The whole course had to be rebuilt.'

That determination is balanced by great loyalty to his friends and generosity to all. In turn he is much loved and in Greece he has been made a Visiting Member of the Athens Academy. One of his proposers to that body describes Paddy as a great civilising influence.

A taste of his qualities is to be had in his most recent book, which has just reached the publishers. Between the Woods and the Water, recording the second part of his

walk across Europe, getting as far as the Iron Gates, will be published by John Murray in early 1986. For those addicted to his style this delay may seem long, but the work will be worth waiting for. The third part of his journey, bringing him to Istan- bul itself, is still being pieced together, without any dimming of memory or dulling of immediacy, though he is taking the trouble to return to Bulgaria over 50 years after his first visit.

Previous page

Previous page