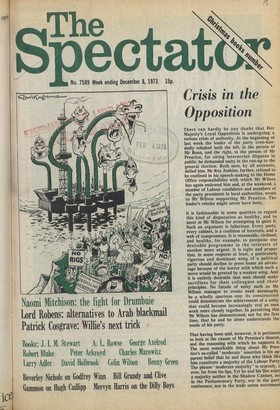

Crisis in the Opposition

There can hardly be any doubt that Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition is undergoing a serious crisis of authority. At the beginning of last week the leader of the party even-handedly rebuked both the left, in the person of Mr Benn, and the right, in the person of Mr Prentice, for airing internecine disputes in public: he demanded unity in the run-up to the general election. Both men, by all accounts, defied him. Mr Roy Jenkins, further, refused to be confined in his speech-making to the Home Office responsibilities with which Mr Wilson has again endowed him and, at the weekend, a number of Labour candidates and members of the party prominent in local authorities, wrote to Mr Wilson supporting Mr Prentice. The leader's rebuke might never have been.

It is fashionable in some quarters to regard this kind of disputation as healthy, and to sneer at Mr Wilson for attempting to quiet it. Such an argument is fallacious. Every party, every cabinet, is a coalition of interests, and a web of compromises. It is reasonable, civilised, and healthy, for example, to postpone one desirable programme in the interests of another more urgent. It is right and proper that, in some respects at least, a particularly vigorous and dominant wing of a political party should decline to press home an advantage because of the horror with which such a move would be greeted by a weaker wing. And it is entirely desirable that men should make sacrifices for their colleagues and their principles. No facade of unity such as Mr Wilson manages to create need necessarily be a wholly spurious one: its construction could demonstrate the achievement of a unity that could become increasingly real as men work more closely together. In perceiving this Mr Wilson has demonstrated, not for the first time, that he and he alone understands the needs of his party.

That having been said, however, it is pertinent to look at the causes of Mr Prentice's dissent, and the reasoning with which he supports it. The most remarkable thing about Mr Prentice's so-called 'moderate' assertion is his ap. parent belief that he and those who think likt him constitute a majority of the Labour Party The phrase 'moderate majority' is scarcely, i ever, far from his lips. Yet he and his like enjoy a majority neither in the Shadow Cabinet, no in the Parliamentary Party, nor in the part: conference, nor in the trade union movemen1 which is such an integral part of the whole Labour effort. This may be judged highly regrettable, but it is none the less a fact. Since the election defeat of 1970 the Labour Party has moved substantially to the left, and in a future Wilson government the right could at best hope to act as a moderating influence on left-wing ministers, just as, last time around, the left did the same for the then majority. This may well lose votes: it is just possible, if it is presented fairly, that it may win them. In any event, there is nothing to be gained by denying the truth. What must be sought is party unity with the acceptance of a left-wing domination. And none of the posturings of Mr Prentice and his GLC allies can change that. Better by far to face the truth, and tell the truth to the people. It is now the duty of the Labour right to buckle down to their jobs, even if they are priming their weapons for what happens after the next election.

Chilean refugees

It is a great pity that British foreign policy towards Chile, hitherto impeccable, has been disfigured by the decision of the Government and the Foreign Office to consider admitting Chilean refugees to Britain. Though far from the first, Britain was one of the countries which early recognised Admiral Pinrochet's administration in Santiago, in accordance with the time-honoured principle that those in charge and control of a country's territory should be recognised as its rulers, save when a state of war exists. There was then a great deal of mindless agitation against both the Admiral and our own Foreign Secretary, and it now appears that the Government's willingness to consider applications from refugees was brought into being by that agitation.

The great majority of those who wish now to leave Chile will be Marxists and diehard opponents of the new government. There can be no obligation on Britain's part towards them, and the remembered confusion of the Dutschke affair should warn us that such agitators Can be very difficult to get rid of, once admitted, however good a Home Secretary's case. In any event, such diehards, and even far more respectable critics of Admiral Pinrochet and his ministers, have no difficulty in finding refuge elsewhere on their own continent. Cuba, in the case of the first group, and Mexico in the case of the second, have made clear their willingness to admit Chileans. There is no reason why Britain, still faced with complications arising from the East African Asian exodus, and owing duty above all to her own passport holders, should make herself a dumping ground for the dissident citizens of a South American state.

The decline of Herr Brandt

Like President Nixon, Herr Willy Brandt, the Chancellor of West Germany, has made his most marked contribution to politics in the field of foreign policy. His determination to procure a ddtente in central Europe led to the Ostpolitik; and the European fervour with which he seeks to expunge, not the memory, but the danger of the recurrence of German aggression and the consequent war guilt, has led to recent proposals for accelerating the coagulation of the member countries of the EEC. Herr Brandt has been treated with unusual respect by his fellow statesmen, and his beating of the breast over Germany's past, has made the Governments of other countries especially unwilling to criticise him.

Yet a great deal of what he has been doing is inimical to the interests of the other European countries. The Ostpolitik is of doubtful benefit, especially as it encourages relaxation on the part of NATO, and his ideas on European unity are dangerous, certainly to the national interests of Britain and France. Now, it appears, Herr Brandt is rapidly losing the allegiance of his own people. The opposition Christian Democrats have a lead over him in the opinion polls of 12 per cent; and more and more members of his own Social Democratic Party are beginning to feel that he would make a better President than Chancellor. His unsteadiness in office was amply demonstrated during the tragic events at the Munich Olympics; his unreliability as an ally made clear when he sided with the Arabs in the current Middle Eastern dispute, having earlier promised sustenance to Israel; and his handling of the German economy bids fair to undo the priceless legacy of prosperity left by Dr Erhard. The sooner Herr Brandt is promoted the better.

Ireland on the pill

It is very much to be welcomed that the Senate of the Irish Republic has given a first reading to Senator Mary Robinson's bill to legalise contraception in the southern part of the island. As Dr Conor Cruise O'Brien pointed out in a weekend speech, the simple recent removal of Article 44 of the Republic's constitution, which had conferred a special position on the Roman Catholic Church, was nowhere near enough to assuage the doubts and fears of Ulster Protestants about the dangers of persecution in a united Ireland. It is absolutely certain that only the total removal of all discrimination against non-Catholics in the laws of the Republic will even begin to remove the barriers of distrust in the mind of the Northern Protestant.

It is easy for the Englishman or the Scot or the Welshman to suppose that Protestant fears are groundless. Has not the Republic a Protestant 'Prime Minister? Do not the representatives of the Southern Irish Anglo-Irish class reassure us regularly that nothing as nasty as discrimination could exist in their happy country? But it is not very long since the party now dominant in the Dublin coalition, Mr Cosgrave's Fine Gael, knuckled under to a fiat from the Archbishop of Dublin against the provision of free medical attention in Irish hospitals. Nor is it very long since Redemptorist priests patrolled the aisles of cinemas in Limerick ensuring that men and women sat in different parts of the buildings. And most Protestants will all too readily remember the weasel words of Cardinal Conway on con traception, to the effect that all good Protestants would be found in support of the anti contraception Papal encyclical Humanae Vitae. The Republic has a long way to go before it is an adequate home for non-Catholics: Senator Robinson has taken a useful first step towards making it so.