Press

Memories of Hugh

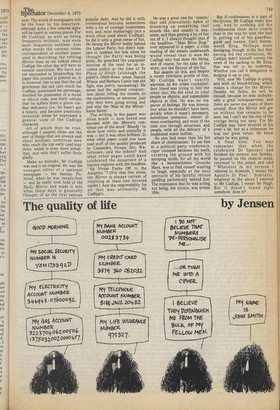

Bill Grundy

The first, and indeed the only, time I appeared on a television programme with Hugh Cudlipp, we preceded it with dinner in a penthouse somewhere in that

garish Mirror building overlooking Holborn Circus. The staff either didn't or wouldn't work overtime waiting on us — considering the company Mr Cudlipp was keeping, I strongly suspect the latter — so Mr Cudlipp served the meal himself. With a panache, as I remember. He opened some excellent claret himself. With a flourish, as 1 remember. And after the meal he offered round his biecigars. With flamboyance: as I remember. The flamboyance was much needed, for, as we lit up, he explained that they weren't actually his cigars at all'. "They're Den Ryder's really," he said. Take another one for later."

It was a revealing remark. Even more revealing was the way Mr Cudlipp said it. He reminded me strongly of the burglar depicted in a verse I learnt at my mother's knee:

Down the stairs he softly stole, His bag of chink he chunk. And many a wicked smile he smole, And many a wink he wunk.

It was an extremely wicked smile he smole as he pressed another

cigar on me. It was a rather special smile, too. ROr this was one that actually extended to his eyes, instead of just hovering around his teeth, as many of Mr Cudlipp's smiles 'do.

At the TV centre, as the floor manager told us there was half a minute to go, Mr Cudlipp stubbed out his King Ryder-sized cigar and lit up something about the size of a whiff. It was superbly timed. Whether it was conscious or not, I don't know. It could well have been an unthinking manifestation of Mr Cudlipp's.ability, at his best, to identify with your average man. Or it could have been cold, calculating Cudlipp thinking that a whiff was more fitting for the public image of the boss of the people's paper. Either way, only Mr Cudlipp could have done it.

Mr Cudlipp is retiring at the end of this month, as we all know by

now. The world of newspapers will be the loser by his departure, although quite a few relieved sighs will be heard at various places. For Mr Cudlipp, as well as being frequently brilliant, was even more frequently ruthless. Just what words the veteran crime correspondent of another paper used in describing the retiring Mirror boss as we talked about Cudlipp the other day will have to remain unwritten. We have not yet succeeded in fireproofing the paper this journal is printed on. It is, however, fair to say that the old gentleman did not care much for Cudlipp, questioned his parentage, doubted his possession of a moral or ethical code, was fairly certain that he suffers from a grave cardiac deficiency (i.e., he hasn't got a heart), and became positively lavatorial when he expressed a general view of the Cudlipp character.

All of which may be true, although I suspect those are the sort of things that are always said about brilliant, ambitious men who reach the top early (and stay there, which is even more irritating), and who don't suffer fools gladly.

Make no mistake, Mr Cudlipp was and is an original. He was the youngest editor of a national newspaper — the Sunday Pictorial, when he was twenty-four — and he really took hold of the Daily Mirror and made it into what these days is generally thought of as the first serious popufar daily. And he did it with tremendous bravura, sometimes with a lot of courage (sometimes not), and, most endearingly (not a word often used about Cudlipp), he did it with a great sense of fun. He swung the Mirror boldly behind the Labour Party, but didn't hesitate to lambast the lads when he thought the Party was being potty. He preached the unpopular doctrine of the need for an incomes policy at the time of In Place of Strife (although the paper's climb-down when Harold Wilson and Barbara Castle lost the fight was pretty nauseating). He never had the sightest compunction about telling the miners, or the steelworkers, or whoever, just why they were going wrong and just why the 'Man in the Mirror' knew better.

The writing in the paper was often brash — how bored one became with the Mirror's continual use of the word ' Bloody ' to show how virile and unstuffy it was — but it was often brilliant. In what other paper could you have read stuff of the quality produced by Cassandra, Proops, Zec, Waterhouse, and the others? And what other paper could have celebrated the departure of a famous explorer with the headline, "Sir Vivian Fuchs Off to the Antarctic "? (For that line alone, the Mirror is always certain of retaining at least one devoted reader.) And the responsibility for all that was ultimately Mr Cudlipp's.•

He was a great one for 'stunts,' that odd journalistic habit of dreaming up something that sounds like, and usually is, nonsense, and then getting a lot of fun out of it. I always thought that if the headline "Man Bites Dog" ever appeared in a paper, a close reading of the details underneath would reveal that it was Mr Cudlipp who had done the biting, and of course, for the sake of the story, not the flavour of the fur. But despite all this, and despite a recent television profile of him, Mr Cudlipp wasn't exactly wartless, as my crime correspondent friend was trying to hint the other day. He did tend to treat people as objects, and expendable objects at that. He was no respecter of feelings. He was insensitive when he shouldn't have been, prickly when it wasn't necessary, sometimes pompous, almost always overbearing, and most of the time tore through situations, and people, with all the delicacy of a maddened water buffalo.

He also had more than his fair share of charlatanism. To see him at a political party conference, cigar clamped between his teeth, covering the ground with his stooping stride, for all the world like a moustacheless Groucho Marx, was to find oneself wanting to laugh, especially at the sorry spectacle of his faithful retinue padding pathetically behind him. The impression that he was acting, not being, the tycoon, was irresistible.

But if ruthlessness is a sign of the tycoon, Mr Cudlipp really was one. And in nothing did his ruthlessness show more clearly than in the way he took the lead in getting rid of his guardian, guide and mentor, Cecil Harmsworth King. Perhaps more damaging, though, is the fact that having led the revolution, Mr Cudlipp didn't himself convey the news of the sacking to Mr King; that was left to an underling. Whether you call it delegation or dodging is up to you.

Well, now Mr Cudlipp is going, and with no blood-letting, which makes a change for the Mirror. Despite his faults, he will be missed, because he was undoubtedly a great newspaperman, and there are never too many of them around. How the Mirror will get on without him remains to be seen. but I can't see the rest of the voyage being too easy. For Mr Cudlipp may have shouted at his crew a bit, but as a helmsman he hckd one great virtue. He knew where he was going.

• A final note. You may remember that when the celebrated Dr Spooner had finished his sermon one Sunday. he paused on the chancel steps, returned to the pulpit and said "Wherever in my sermon I referred to Aristotle, I meant the Apostle St Paul." Similarly, wherever in the above I referred to Mr Cudlipp, I meant Sir Hugh. But it doesn't sound right somehow, does it?

Previous page

Previous page