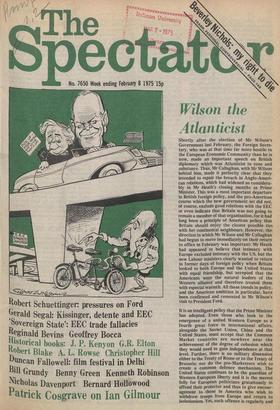

Wilson the Atlan,ticist

Shortly after the election of Mr Wilson's Government last February, the Foreign Secretary, who was at that time far more hostile to the European Economic Community than he is now, made an important speech on British diplomacy which was Atlanticist in tone and substance. Thus, Mr Callaghan, with Mr Wilson behind him, made it perfectly clear that they intended to repair the breach in Anglo-American relations, which had widened so considerably in Mr Heath's closing months as Prime Minister. This was a most important departure in British foreign policy, and the pro-American course which the new government set did not, of course, exclude good relations with the EEC or even indicate that Britain was not going to remain a member of that organisation, for it had long been a principle of American policy that Britain should enjoy the closest possible ties with her continental neighbours. However, the direction in which Mr Wilson and Mr Callaghan had begun to move immediately on their return to office in February was important: Mr Heath had appeared to believe that intimacy with Europe excluded intimacy with the US, but the new Labour ministers clearly wanted to return to former days of foreign policy when Britain looked to both Europe and the United States with equal friendship, but accepted that the Americans were the natural leaders of the Western alliance and therefore treated them with especial warmth. All these trends in policy, and the American ambition in particular, have been confirmed and cemented in Mr Wilson's visit to President Ford.

It is an intelligent policy that the Prime Minister has adopted. Even those who look to the emergence of a united Western Europe as a fourth great force in international affairs, alongside the Soviet Union, China and the United States, must accept that the Common Market countries are nowhere near the achievement of the degree of cohesion which they would need to gain independence at that level. Further, there is no military dimension either to the Treaty of Rome or to the Treaty of Brussels; nor do the pro-Marketeers wish to create a common defence mechanism. The United States continues to be the guardian of Western European liberty and it is the merest folly for European politicians gratuitously to offend their protector and thus to give encouragement to those in America who wish to withdraw troops from Europe and return to isolationism. Yet, such offence is regularly and stupidly given both by the Common Market countries collectively and by some of them individually, especially France. Mr Wilson and Mr Callaghan have correctly seen — as Mr Heath did not — that every unnecessary quarrel with the United States weakens the security of Western Europe and the credibility and strength of the Western alliance.

What is absolutely true in matters of defence is almost as true in trade and economic matters. Before Mr Wilson and Mr Callaghan went to Washington, Mr Healey was there, as spokesman for the EEC finance ministers. He is not the most agreeable or co-operative of men, and his personality undoubtedly had an unfortunate effect on the American politicians with whom he had to deal: Mr Wilson, it appears, had some difficulty in repairing the harm the Chancellor had done. But Mr Healey — who was not even allowed to see President Ford — was himself burdened with the task of presenting the Americans with exceptionally selfish and unacceptable demands in the international monetary field made by the European countries collectively. These demands, which the patient Americans went a little way to meet, were essentially designed to protect the EEC and its weird economic structure without regard to the effect their performance might have on the United States herself or on the EEC's other trading partners. It is now clear that Mr Wilson does not wish to go along with either the selfishness or the thoughtlessness of Britain's EEC partners; and that he is sensibly aware of the beneficial effect on international trade which the President's economic measures may have if Congress accepts them and the American people respond to them. It was thus of considerable value that Mr Wilson and Mr Ford met, that they established a relationship of mutual confidence and good fellowship and that they found themselves thinking alike in economic and trade matters. It is always a difficult and dangerous matter to alter a long-established and well-tried foreign policy, though diplomatic revolutions are sometimes necessary. Mr Heath was, we believe, wrong to try to destroy the Atlantic axis on which British foreign policy has been based since 1940, and Mr Wilson has been right in attempting to repair it.

Oil swaps

During a week in which the Prime Minister was defending to the President of the United States the decision to tz.ke a referendum on the Common Market issue, it was revealed that Dr Jamshid Amouzegar, the chief Iranian delegate to the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries, was suggesting that Iran was willing to lend oil to Britain to be repaid by a similar quantity of oil — plus, presumably, interest also in kind — from North Sea supplies when they become available. Saudi Arabia and Venezuela have since intimated that they, too, are interested in transacting similar business with this country.

Typically, there has been no response from Britain — Mr Varley's Department of Energy intimated that they had not hea& of the offers — though preliminary indications from the Foreign Office and the Treasury speak of our response as being 'lukewarm' which, making allowances for diplomatic language, may be presumed to mean a definite 'No'. Yet an oil-for-oil barter deal — using what in financial circles would be described as 'slow notes' — would reduce pressure on sterling, dollar or gold reserves and be to this country's immense trade advantage. It would give us the fuel and oil feed-stocks at an effectively lower price than the rest of the world which is not in a position to barter future production. Significantly, the EEC would be put at a disadvantage. A barter transaction would take pressure off our exporting industries, too reliant already on specialised business being generated by the Middle East. Further, there are good grounds for believing that the international price of oil is already falling and will fall further. By repaying what we borrow now with North Sea production at a time when the price is lower would clearly be to our profit, though it has to be admitted that the Middle East countries, which have been wary of the dollar, might consider the value of oil, by itself, inadequate as a `numeraire', ironic as this may seem.

The reason for the British Government's rejection of the proposal, if they have given it any thought at all, is doubtless that such deals are Schachtian in concept, tying us in with certain countries to the disadvantage of other oil producers like Nigeria who are unable to afford to delay receipts. But probably more telling is our present commitment to Brussels: the terms of our trade with Europe and with the rest of the world would swing to our advantage if the price of oil were taken out of immediate costs, especially if we were allowed the business of oil arbitrage. Such arguments against concluding oil swaps hardly stand scrutiny. We have been assured by both the Prime Minister and Mr Heath that the oil in the North Sea indeed belongs to this country (though they have admitted that under the T:eaty of Rome we are not permitted to restrict supplies of the oil reaching the rest of the Community at the same price at which it is sold to our home industry). Thus there seems no case against our concluding these arrangements now, while we are in the EEC, and certainly not after June when we are once more, by the grace of the British people, able to make the kind of independent decisions which, incidentally, would have been taken without compunction by the French if they had been fortunate enough to be in our present situation.