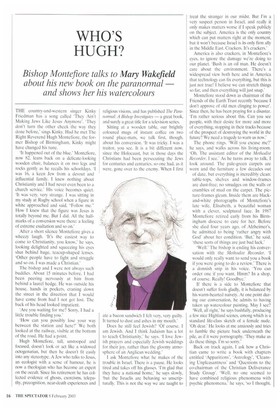

WHO'S HUGH?

Bishop Montefiore talks to Mary Wakefield

about his new book on the paranormal — and shows her his watercolours

THE country-and-western singer Kinky Friedman has a song called 'They Ain't Making Jews Like Jesus Anymore'. 'They don't turn the other cheek the way they done before,' sings Kinky. Had he met The Right Reverend Hugh Montefiore, the former Bishop of Birmingham, Kinky might have changed his tune.

'It happened out of the blue.' Montefiore, now 82, leans back on a delicate-looking wooden chair, balances it on two legs and rocks gently as he recalls his schooldays. 'I was 16, a keen Jew from a devout and influential family. I knew nothing about Christianity and I had never even been to a church service.' His voice becomes quiet. 'It was very, very strange. I was sitting in my study at Rugby school when a figure in white approached and said, "Follow me." How I knew that the figure was Jesus is totally beyond me. But I did. All the hallmarks of a conversion were there: a feeling of extreme exultation and so on.'

After a short silence Montefiore gives a wheezy laugh. 'It's the easiest way to come to Christianity, you know,' he says, looking delighted and squeezing his eyes shut behind huge, teacup-shaped lenses. 'Other people have to fight and struggle and so on. I was made a Christian.'

The bishop and I were not always such buddies. About 15 minutes before, I had been peering nervously at him from behind a laurel hedge. He was outside his house, hands in pockets, craning down the street in the direction that I would have come from had I not got lost. The back of his head looked impatient.

Are you waiting for me? Sorry, I had a little trouble finding you.'

'How can you possibly lose your way between the station and here?' We both looked at the railway, visible at the bottom of the road. He had a point.

Hugh Montefiore, tall, unstooped and focused, doesn't look or act like a widowed octogenarian, but then he doesn't fit easily into any stereotype. A Jew who talks to Jesus, an ecologist with a sense of humour, he is now a theologian who has become an expert on the occult. Since his retirement he has collected evidence of ghosts, exorcisms, telepathy, precognition, near-death experiences and religious visions, and has published The Paranormal: A Bishop Investigates — a great book, and surely a great title for a television series.

Sitting at a wooden table, our brightly coloured mugs of instant coffee on two round place-mats, we talk first, though, about his conversion. 'It was tricky. I was a traitor, you see. It is a bit different now, since the Holocaust, but in those days the Christians had been persecuting the Jews for centuries and centuries, so one had, as it were, gone over to the enemy. When I first

ate a bacon sandwich I felt very, very guilty. It turned to dust and ashes in my mouth.'

Does he still feel Jewish? 'Of course. I am Jewish. And [think Judaism has a lot to teach Christianity,' he says. 'I love Jewish prayers and especially Jewish weddings for their joy, rather than the gloomy atmosphere of an Anglican wedding.'

I ask Montefiore what he makes of the trouble in Israel. There is a pause. He looks tired and takes off his glasses. 'I'm glad that they have a national home,' he says slowly, tut the Israelis are behaving so unscripturally. This is not the way we are taught to treat the stranger in our midst. But I'm a very suspect person in Israel, and really it only makes matters worse if I speak publicly on the subject. America is the only country which can put matters right at the moment, but it won't because Israel is its only firm ally in the Middle East. Crackers, It's crackers.'

America is also crackers, in Montefiore's eyes, to ignore the damage we're doing to our planet. 'Bush is an oil man. He doesn't care about the environment. There's a widespread view both here and in America that technology can fix everything, but this is just not true! I believe we can stretch things so far, and then everything will just snap.'

Montefiore stood down as chairman of the Friends of the Earth Trust recently `because I don't approve of old men clinging to power'. Since then, he has been praying for a disaster. 'I'm rather serious about this. Can you see people, with their desire for more and more of everything, stopping in their tracks because of the prospect of destroying the world in the future? We need a tragedy to warn us now.'

The phone rings. Will you excuse me?' he says, and walks across his living-room. 'Oh. The assistant editor of the Methodist Recorder. I see.' As he turns away to talk, I look around. The pale-green carpets are worn and the furniture a few decades out of date, but everything is incredibly clean: table-tops, shelves and window-frames are dust-free; no smudges on the walls or crumbles of mud on the carpet. The picture-frames gleam. Inside them are blackand-white photographs of Montefiore's late wife. Elisabeth, a beautiful woman with a clever, sculptural face, In 1987 Montefiore retired early from his Birmingham diocese to care for her. Before she died four years ago, of Alzheimer's, he admitted to being 'rather angry with God' about her condition. 'But,' he said, 'these sorts of things are just had luck.'

`Well.' The bishop is ending his conversation with the Methodist Recorder. `I would only really want to send you a book if you were going to do a review.' There is a donnish snip in his voice. 'You can order one if you want. Hmm? In a shop, of course. Really! Goodbye.'

If there is a side to Montefiore that doesn't suffer fools gladly, it is balanced by his warm-hearted naivety. At one point during our conversation, he admits to having taken up watercolour painting. May I see? 'Well, all right,' he says bashfully, producing a few nice Highland scenes, among which is a standard life-class sketch of a female nude. 'Oh dear.' He looks at me anxiously and tries to fumble the picture back underneath the pile, as if it were pornography. 'They make us do these things. I'm so sorry.'

Back on track again, I ask how a Christian came to write a book with chapters entitled 'Apparitions', 'Astrology', 'Cleansing Unpleasantness' and 'Questions to the co-chairman of the Christian Deliverance Study Group'. 'Well, no one seemed to have combined religious phenomena with psychic phenomena,' he says, 'so I thought, why don't you do it yourself? The more I found Out, the more interested I became.'

And the more interested he became, the crosser he grew with Richard Dawkins, Oxford University's front man for neoDarwinism. In the conclusion of The Paranormal. Montefiore responds to a jibe of Dawkins's: 'No, no, Mr Dawkins! I do not know about ogres or bogeymen, because I am not sure what they are. But I am sure about psychic realities and I have given evidence of them in this book.'

rather like Dawkins personally, actually,' says Montefiore, clasping his hands and twiddling his thumbs. 'My problem with him is that he says psychics are wasting their time, but he doesn't bother to investigate the phenomena.'

If Dawkins would just ask around, according to Montefiore, he'd find that other-worldly experiences, especially of God, are more common than we imagine. 'I'm sure that about 50 per cent of people have religious experiences,' he says. 'Nearly everyone has had a psychic experience. But how they interpret it depends on their presuppositions.'

My own presuppositions are keeping up with Montefiore's until he starts to explain his psychic theory of the Bible. 'There are times in the New Testament when Jesus knows what's going on in people's minds,' he says. 'I think these are examples of telepathy. Remember the story of the Transfiguration, when Jesus came down from the mountain shining white? That's not miraculous, it's

paranormal. If you think about it, Jesus also sees into the future. Look at the time that He told Peter he would deny Him three times.'

But if Jesus is His son, surely God wouldn't begrudge Him a few super powers?

'I think that is a rather naive view,' says Montefiore. 'It was because Jesus was fully human that He had psychic gifts, not because He was the Son of God.'

But, I try again, if you attribute all the magic stuff in the Bible to man's natural psychic abilities, what evidence is there that Jesus was the Son of God? 'But, but, but,' says Montefiore, smiling. 'The descriptions of paranormal activity in the Bible are not evidence for or against God or Jesus being His son. The reason I know Jesus is the Son of God is because when I am with Him I feel that I am in the presence of God, which is more powerful than anything else.'

Trumped again. We sit for a few minutes in silence while I gum and fidget, unable to articulate all the things I don't understand. The bishop spins my Dictaphone round in circles on the table, which, when I play it back later, makes a sound like sandpaper on stone. 'Look,' he says, kindly. 'I don't pretend to understand everything about the paranormal and I think this is a very curious way of making the world, but the evidence is that these things happen.'

The Paranormal: A Bishop Investigates (Up Front Publish* £9.99) can be ordered on 0870 005 2150.

Previous page

Previous page