He who blasts last

Peter Ackroyd

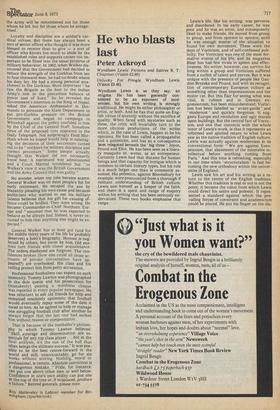

Wyndham Lewis: Fictions and Satires R. T. Chapman (Vision 62.80) Unlucky For Pringle Wyndham Lewis (Vision 63.40)

Wyndham Lewis is as they say, an enigma. He has been generally considered to be an exponent of modernism, but his own writing is strongly traditional. He might be either philosopher or artist, or both. And he has that quite un-English virtue of quantity without the sacrifice of quality. When faced with mysteries such as these, the critic will invariably turn to the more obvious productions of the writer which, in the case of Lewis, happen to be his opinions. He has been called a propagandist and a polemicist, and has as a consequence been relegated beneath the ' big three ': Joyce. Pound and Eliot. He has been seen as a literary mosquito or, worse, as an entrepeneur. Certainly Lewis had that distaste for human beings and that capacity for intrigue which is common to certain literary types, but his role is a much larger one than is commonly assumed. His polemics, against Bloomsbury for example, were pronounced from a thorough if militant understanding of British culture. Lewis saw himself as a keeper of the faith, and there is a spirit and range of enquiry within his writing that has been seriously undervalued. These two books emphasise that range. Lewis's life, like his writing, was perverse and disordered. In his early career, he was poor and he was an artist, and consequently liked to make friends. He moved from group to group, and from opinion to opinion, until he was enough master of the situation to found his own movement. These .were the days of Vorticism, and of self-confessed pub licity. For Vorticism was one of the most for

mative events of his life, and its magazine Blast has had few rivals in spleen and effec

tiveness. No writer, however, can survive for long within a group and Vorticism suffered from a surfeit of talent and nerves. But it was unique with the presence of people like Gaudier-Brezska and Pound, and with its recognition of contemporary European culture as something other than impressionism and the motor car. But this flair for seeing what was vital, in cubism and in German expressionism, has been misunderstood; Vorticism has been labelled as 'avant-garde' and ' modernist ' and quickly forgotten. It suggests Europe and revolution and ugly murals upon buildings. But the central fact of Vorticism, and one that connects with the whole tenor of Lewis's work, is that it represents an informed and spirited return to what Lewis saw as the native tradition of English culture. Lewis was actually against modernism in its conventional form: "We are against Europeanism, that abasement of the miserable intellectual before anything coming from Paris." And this tone is refreshing, especially in our time when ' structuralism ' is fast becoming the new orthodoxy within the universities of England.

Lewis saw his art and his writing as a return to the centre of the English tradition. Whether this tradition is real or not is not the point; it became the value from which Lewis could direct his satire and polemic. It represented a standard against which the prevailing forces of constraint and academicism could be placed. He put his finger on the dis

ease within English culture, and constructed a cure. It was a major effort and one that found him few friends. Although it was ultimately unsuccessful, it changed the face of English culture. And in these times, when an American provincialism and cult academicism are our sole resources, the nerve and spirit of Lewis deserves to be honoured.

But Lewis is by no means an entirely satisfactory writer. There is something too heated and assertive about his writing, and it often suffers from an excess of point. He knows what he is saying, but not whom he is saying it to. There are certain writers who can connect the movement of their literature with philosophical or political statement, but the balance in Lewis's work is unsteady. It is like that of a bright young man who will sometimes moralise without having a morality.

Something of this emerges from Robert Chapman's critical study. The book traces very carefully the progress of Lewis toward more and more dogmatic and sententious statement, and toward the idea of himself as Swift or Juvenal lashing the follies of the age.

Chapman shows that this entails a loss of subtlety in Lewis's later work, a retreat into a kind of hardness and fantasy that is incongruous with the poetic vigour and detail of his earlier writing.

But Chapman generally refrains from making critical judgments about the quality and development of Lewis's writing — it is not quite the thing nowadays to judge — and traces instead the 'ideas' or symbols which occur in the writing. The book is both critical history and commentary, and it covers that fashionable , notion of ' dialectic' which Chapman discovers in Lewis's work, a dialectic between mind and body, between ideas and human existence. There is nothing particularly surprising about this — the divorce between idea and reality is clearly the foundation of any satiric work — but the themes of Lewis are discussed by Chapman with tact and expertise. The case for Wyndham Lewis as a satirist could not be better made, although I suspect that there is more to be said.

Chapman also conveys well the atmosphere of those times, which now seem so distant. It is extraordinary, at this late date, to read of the excitement and interest which artistic manifestoes and exhibitions aroused. Even the daily press — even, I might add, the Daily Express — took an intelligent if slightly haughty interest in the ideas of 'the artist' and the welfare of his art. There was a kind of cultural health in London, a sense of intrigue and novelty that has now been dissipated in our more populist time. But if Chapman evokes the spirit of London, he also brings home the courage of the middle-aged Lewis in standing apart from it, and the denigration which he had to endure because of his stand. After his attachment to Vorticism, Lewis seemed to step apart from the literary and cultural world. His refusal to entertain a fashionable socialism in the thirties made him a target for liberals and intellectuals alike. He became a solitary man, for hell has no spite like a liberal intellectual scorned. He was detested for his principles, and the cultural establishment never forgave him. The satire came from a real wound.

I suggest there may be more to Lewis than this paranoid, satirical persona. And it is this further element which emerges in the collection of Lewis's published and unpublished short stories, Unlucky For Pringle. They range from 1914 to the 1950s, and they present a miniature history of Lewis's art. The short story form is a difficult one to master, especially for a propagandist and satirist. But this is its advantage for seeing Lewis entire. For it evokes the more imaginative areas of his writing, and excises that moralising and, tendentiousness of which he is capable. Although Lewis did not see life whole, he saw it

clearly and steadily; Unlucky For Pringle is a surprisingly fine book.

Lewis had an eye for the dotty and the deranged from the beginning of his writing, and it is simply his analysis of their moral condition which changes. The progrss of his writing never did run smooth, and his position as both moralist and imaginative writer becomes more and more difficult to sustain. In the stories of the 1950s which are reprinted in this volume, the prose has become a heavier thing. Lewis comes to dwell more and more upon mental and moral deformity, on what is unlucky or odd. The humour vanishes. In 'Doppleganger,' the story of the cuckolding of an ageing poet, the descriptions of mood and conversation are still sharp but the action and narrative are tendentious and simplistic. Lewis's imagination has become vulgar, as if a bright young man has been undeceived by ' life ' and yet has nowhere else to go. In the later work of Lewis, it is the moral which is the thing. And this " lonely old volcano," who once had so much to say in a divided culture, was left to cultivate his own opinions.

Previous page

Previous page