ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Marcel Duchamp (Palazzo Grassi, Venice, till 18 July)

The enigma exposed

Giles Auty

The audience for 20th-century art can be divided conveniently between those who view Marcel Duchamp as a seminal but Positive figure, and those who see his influ- ence on subsequent art as a severe nui- sance or worse. It is to the great credit of Fiat, who own the last of the great Vene- tian palaces to be built, to the design of Giorgio Massari (1687-1766), to assist those who can visit this comprehensive exhibition to make their own considered assessments. Was Marcel Duchamp a sar- donic intellectual prankster but possessor, nevertheless, of a profound mind, or a per- manently petulant artistic child who demanded constant reassurance and the adulation of lesser beings? In short, was he a joke or a joker? I should admit here that I have seen him always simply as a non- intellectual's idea of an intellectual, and find nothing in this huge show to cause me to change my mind. But I imagine most commentators will shrink from taking on the reputation of so shadowy a figure who is venerated especially by those whose own aggressively modernist attitudes often con- ceal a profound hatred of the more estab- lished traditions of European art. Nor, as the inventor of the artistic 'ready-made', heed Duchamp be blamed necessarily if he has become the patron saint in art of the Young and talentless. Duchamp merely Opened the floodgates which have threat- ened to engulf art subsequently under a tidal wave of 'conceptual' mediocrity.

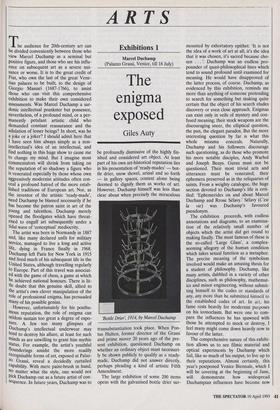

The artist was born in Normandy in 1887 and, like many declared unfit for military service, managed to live a long and active life, dying in France finally in 1968. Duchamp left Paris for New York in 1915 and lived much of his subsequent life in the United States, although travelling regularly to Europe. Part of this travel was associat- ed with the game of chess, a game at which he achieved national honours. There is lit- tle doubt that this genuine skill, allied to the artist's own clever manipulation of the role of professional enigma, has persuaded Many of his possible genius. However, unfortunately for his posthu- mous reputation, the role of enigma can seldom sustain too great a degree of expo- sure. A few too many glimpses of Duchamp's intellectual underwear may tend to destroy his allure, at least for such minds as are unwilling to grant him mythic status. For example, the artist's youthful flounderings amidst the more readily recognisable forms of art, exposed at Palaz- zo Grassi, reveal a decidedly curtailed capability. With mere paint-brush in hand, ri0 matter what the style, one would not Pick Duchamp out as a future artist of con- sequence. In future years, Duchamp was to be profoundly dismissive of the highly fin- ished and considered art object. At least part of his own art-historical reputation lies in his presentation of 'ready-mades' — bot- tle drier, snow shovel, urinal and so forth — in gallery spaces, context alone being deemed to dignify them as works of art. However, Duchamp himself was less than clear about when precisely the miraculous 'Bottle Drier', 1914, by Marcel Duchamp transubstantiation took place. When Pon- tus Hulten, former director of the Grassi and prime mover 20 years ago of the pre- sent exhibition, questioned Duchamp on whether an ordinary object must necessari- ly be shown publicly to qualify as a ready- made, Duchamp did not answer directly, perhaps pleading a kind of artistic Fifth Amendment.

The large exhibition of some 200 items opens with the galvanised bottle drier sur- mounted by exhortatory epithet: 'It is not the idea of a work of art at all, it's the idea that it was chosen, it's sacred because cho- sen . Duchamp was an endless pro- pounder of quasi-philosophical lines which tend to sound profound until examined for meaning. He would have disapproved of the latter process, of course. Duchamp, as evidenced by this exhibition, reminds me more than anything of someone pretending to search for something but making quite certain that the object of his search eludes discovery or even close approach. Enigmas can exist only in veils of mystery and con- fused meaning; their stock weapons are the discouraging sneer, the elliptical question, the pun, the elegant paradox. But the more interesting question by far is what this whole miasma conceals. Naturally, Duchamp and his followers discourage such questioning, as do those who promote his more notable disciples, Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys. Gurus must not be questioned. Their most trivial acts and utterances must be venerated; their ephemera preserved as in the reliquaries of saints. From a weighty catalogue, the huge section devoted to Duchamp's life is enti- tled: 'Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sdlavy.' Selavy (C'est la vie) was Duchamp's favoured pseudonym. The exhibition proceeds, with endless annotations and diagrams, to an examina- tion of the relatively small number of objects which the artist did get round to making finally. The most famous of these is the so-called 'Large Glass', a complex- seeming allegory of the human condition which takes sexual function as a metaphor. The precise meaning of the symbolism involved would make an amusing thesis for a student of philosophy. Duchamp, like many artists, dabbled in a variety of other disciplines, such as philosophy, mathemat- ics and minor engineering, without submit- ting himself to the codes or standards of any, any more than he submitted himself to the established codes of art. In at, his fame rests heavily for modernist puiposes on his iconoclasm. But were one to com- pare the influences he has spawned with those he attempted to mock or destroy, I feel many might come down heavily now in favour of the latter.

The comprehensive nature of this exhibi- tion allows us to see filmic material and optical experiments by Duchamp which fail, like so much of his output, to live up to their reputations. Almost certainly, this year's postponed Venice Biennale, which I will be covering at the beginning of June, will demonstrate how widespread Duchampian influences have become now in international terms, even though there is far from being a consensus on their merits. I feel the present exhibition is intended as a powerful trailer for these, yet it stands, perhaps, at a turning point in history which may yet see the primacy of the art object, rather than the mere notes for its manufac- ture, restored to its rightful place.

In the face of the father of conceptual- ism, I thank God daily that Velazquez and Rembrandt say — or, more locally, Titian and Veronese — subscribed and submitted in their day to more tangible and definable disciplines. I do not believe they were the worse for it.

Previous page

Previous page