Architecture

The Art of the Process (RIBA, until 16 April) Sacred Space in the Modern Age (Accademia Italiana, until 25 April) The Real Ideal Home (Architecture Foundation, until 16 May)

Design for living

Alan Powers

London is well provided with architec- tural exhibitions at present. At the RIBA (66, Portland Place, W1) an ambitious assembly called The Art of the Process is a valedictory to the presidency of Richard MacCormac who, two years ago, announced a mission to make architecture more accessible to the public while healing stylistic divisions within the profession.

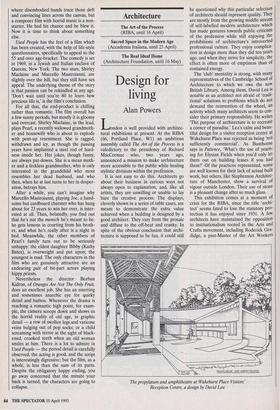

It is not easy to do this. Architects go about their business in curious ways not always open to explanation, and, like all artists, they are unwilling or unable to lay bare the creative process. The displays, cleverly shown in a series of table cases, are meant to demonstrate the extra value achieved when a building is designed by a good architect. They vary from the prosaic and diffuse to the off-beat and cranky. In spite of the obvious conclusion that archi- tecture is supposed to be fun, it could still be questioned why this particular selection of architects should represent quality. They are mostly from the growing middle stream of self-labelled modern architecture which has made gestures towards public criticism of the profession while still enjoying the prohibitions of architecture's introverted professional culture. They enjoy complica- tion in design more than they did ten years ago, and when they strive for simplicity, the effect is often more of emptiness than of contained energy. The 'club' mentality is strong, with many representatives of the Cambridge School of Architecture to which we owe the new British Library. Among them, David Lea is notable as an architect not afraid of 'tradi- tional' solutions to problems which do not demand the reinvention of the wheel, an activity which many architects seem to con- sider their primary responsibility. He writes 'The purpose of architecture is to recreate a corner of paradise.' Lea's calm and beau- tiful design for a visitor reception centre at Wakehurst Place was rejected as being 'not sufficiently commercial'. As Bunthorne says in Patience, 'What's the use of yearn- ing for Elysian Fields when you'd only let them out on building leases if you had them?' Of the practices represented, some are well known for their lack of actual built work, but others, like Stephenson Architec- ture of Manchester, show a survival of vigour outside London. Their use of stone is a pleasant change after so much glass. This exhibition comes at a moment of crisis for the RIBA, since the title 'archi- tect' seems fated to lose the statutory pro- tection it has enjoyed since 1931. A few architects have maintained the opposition to institutionalism rooted in the Arts and Crafts movement, including Roderick Gra- didge, a past-Master of the Art Workers The propylceum and amphitheatre at Wakehurst Place Visitors' Reception Centre, a design by David Lea Guild whose ingenious, imaginative, but unpretentious, new additions to St Edmund's College, Cambridge, would have made a welcome contrast to the monocul- ture of Portland Place.

Touching the question of paradise, but viewing it globally, the exhibition Sacred Space in the Modem Age at the Accademia Italiana (24 Rutland Gate SW7) provokes further thoughts on form and content in architecture. Church building (the exhibi- tion also includes mosques and syna- gogues) challenges the assumptions of rapid change endemic in modern architec- ture. Conviction is necessary, and compro- mise is cruelly exposed. 'I have tested the inane patterns without prejudice, for it is easy to miss Him at the turn of a civilisa- tion,' wrote David Jones in 1966. The selec- tion, taken from an exhibition at the Venice Biennale, includes some beautiful work, although displayed without much information. This building type lends itself to the reworking of traditional solutions, if only because these are valued and loved through use, like the words of the liturgy. It was a pity not to include one of Britain's finest church architects, Francis Roberts of Preston, another example of provincial independence and quality.

A third exhibition shares some of the concerns of the others. At the Architecture Foundation (30 Bury Street, SW1) are dis- played entries for a competition The Real Ideal Home, organised jointly by the Foun- dation, Shelter and the Housing Corpora- tion. In one way, this project for a 'foyer' or small socially oriented hotel for the young homeless in Birmingham shows more clear- ly the way architects work and think than the carefully selected information on show at Portland Place. It shows what can go wrong, particularly when schemes are unbalanced by the domination of a single 'big idea'. The assessors' comments assume a rather simplistic connection between plan form and induced behaviour among the building users. Will the amateur psychology and sociology of architects be taken on trust for ever, even as the tower blocks crumble to the ground?

The winning design, by Ian Simpson of Manchester, is in the high-tech mould of Sir Norman Foster, who was one of the judges. It will, if built to plan, be an impressive and visible gesture towards the solution of a . social problem traditionally addressed by religious groups as much as the state. There is a kind of awed reverence in the foyer idea that seeks to elevate it to a sacred plane, but less sentimental organi- sations like the Salvation Army always understood that saving souls is not a draw- ing-room diversion. Buildings get kicked in the process, and need to stand up without maintenance for years. Will this sleek simu- lacrum of a corporate headquarters prove adequate to the professional needs of its users, or merely flatter the professional pride of architects?

Previous page

Previous page