THE CITY OF HONOURABLE MARTYRS

Radek Sikorski returns to his

old haunts in Afghanistan, a nation still recovering from the horror of war

Herat THE LAST time I went to Herat, the jour- ney took six weeks, on foot and on horse- back. Getting there involved dodging a Soviet helicopter ambush, crossing in and out of communist-held territory, and wear- ing Afghan clothes to escape detection. This time, I arrived on a United Nations shuttle, with nothing more onerous than UN bureaucracy to obstruct me. 'Welcome to the city of honourable martyrs,' pro- claimed a sign on Herat airport's control tower. I wanted to take stock of what the war had done to the Florence of Central Asia.

The Afghan war began in Herat in March 1979 with a Muslim uprising against the Soviet-backed communist regime. The rebellion ended in a massacre: Soviet heli- copters strafed the crowds praying in mosques. The resistance which began in Herat spread to other provinces, however, precipitating the Soviet invasion. Thanks to their fierce reputation, Herat's mujaheddin fighters were special targets of Soviet bom- bardment during the Afghan war — and they became famous for their valour under fire. The bravest of these was Ismael Khan, the leader of the 1979 garrison mutiny, and my guide for part of my journey to Herat in 1986.

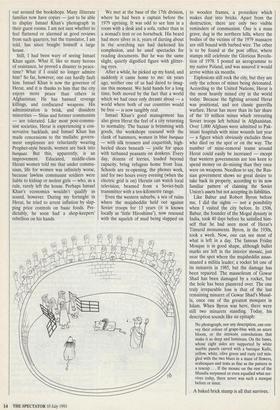

On my first walk through the city as I was passing the money-changers squatting in the dirt behind piles of bank-notes, I was brought up sharply by the sight of a photo- graph on the cover of a book in a window display: it was Ismael Khan, bearded, in a chequered scarf, galloping up from behind a hill at the head of a band of youthful fol- lowers. I had taken the picture in 1987, and the book was my book, in translation: had I forgotten to sign a contract for the Persian- language rights?

In fact, the book has sold well, thanks to an unusual promotional scheme. When Ismael Khan's mujaheddin entered Herat in triumph last year, mullahs at the Friday mosque ordered the faithful to buy copies. Thousands followed the call of divine obli- gation, and I am told that scuffles broke out around the bookshops. Many illiterate families now have copies — just to be able to display Ismael Khan's photograph in their guest rooms. I am not sure whether to feel flattered or alarmed at good reviews from such quarters, but the translator, I am told, has since bought himself a large house.

Still, I had been wary of seeing Ismael Khan again. What if, like so many heroes of resistance, he proved a disaster in peace- time? What if I could no longer admire him? So far, however, one can hardly fault him. Ismael Khan is now the governor of Herat, and it is thanks to him that the city enjoys more peace than others in Afghanistan. He has banned revenge killings, and confiscated weapons. His administration is brisk, and dissident minorities — Shias and former communists — are tolerated. Like most post-commu- nist societies, Herat is experiencing a con- servative backlash, and Ismael Khan has made concessions to the mullahs: govern- ment employees are reluctantly wearing Prophet-style beards, women are back into burquas. But this, apparently, is an improvement. Educated, middle-class Herati women told me that under commu- nism, life for women was infinitely worse, because lawless communist soldiers were liable to kidnap or molest girls — who, as a rule, rarely left the house. Perhaps Ismael Khan's economics wouldn't qualify as sound, however. During my fortnight in Herat, he tried to arrest inflation by slap- ping price controls on basic foods. Pre- dictably, he soon had a shop-keepers' rebellion on his hands.

We met at the base of the 17th division, where he had been a captain before the 1979 uprising. It was odd to see him in a room with a desk and a sofa, rather than in a nomad's tent or on horseback. His beard had more silver in it, years of darting about in the scorching sun had darkened his complexion, and he used spectacles for reading documents. But he was the same slight, quietly dignified figure with glitter- ing eyes.

After a while, he picked up my hand, and suddenly it came home to me: six years ago, neither one of us had dared to imag- ine this moment. We held hands for a long time, both moved by the fact that a world which we had once only dreamt about — a world where both of our countries would be free — is now tangibly real.

Ismael Khan's good management has also given Herat the feel of a city returning to normality. The bazaar is brimming with goods, the workshops resound with the clank of hammers, women in blue burquas — with silk trousers and coquettish, high- heeled shoes beneath — jostle for space with turbaned peasants on donkeys. Every day, dozens of lorries, loaded beyond capacity, bring refugees home from Iran. Schools are re-opening, the phones work, and for two hours every evening (when the electric grid is on) Heratis can watch local television, beamed from a Soviet-built transmitter with a ten-kilometre range.

Even the western suburbs, a sea of ruins where the mujaheddin held out against Soviet troops for 13 years (it is known locally as 'little Hiroshima'), now resound with the squelch of mud being slapped on to wooden frames, a procedure which makes dust into bricks. Apart from the destruction, there are only two visible reminders of communism. One is a mass grave, dug in the northern hills, where the bodies of the victims of the 1979 massacre are still bound with barbed wire. The other is to be found at the post office, where stamps still celebrate the Glorious Revolu- tion of 1978. I posted an aerogramme to my native Poland, and was assured it would arrive within six months.

Explosions still rock the city, but they are only the echoes of mines being detonated. According to the United Nations, Herat is the most heavily mined city in the world today. Because the fighting around Herat was positional, and not classic guerrilla warfare, Herat has more than its fair share of the 10 million mines which retreating Soviet troops left behind in Afghanistan. Over 1,000 Afghans were admitted to Pak- istani hospitals with mine wounds last year — a figure which obviously excludes those who died on the spot or on the way. The number of mine-removal teams around Herat could easily be increased — except that western governments are less keen to spend money on de-mining than they once were on weapons. Needless to say, the Rus- sian government shows no great desire to take back its property, according to its now familiar pattern of claiming the Soviet Union's assets but not accepting its liabilities.

Like Babur and Robert Byron before me, I did the sights — not a possibility when I visited the city before. In 1506, Babur, the founder of the Mogul dynasty in India, took 40 days before he satisfied him- self that he had seen most of Herat's Timurid monuments. Byron, in the 1930s, took a week. Now, one can see most of what is left in a day. The famous Friday Mosque is in good shape, although bullet marks are left in the interior mosaic, just near the spot where the mujaheddin assas- sinated a militia leader; a rocket hit one of its minarets in 1985, but the damage has been repaired. The mausoleum of Gowar Shad has been damaged by a rocket, but the hole has been plastered over. The one truly irreparable loss is that of the last remaining minaret of Gowar Shad's Musal- la, once one of the greatest mosques in Islam. When Byron was here, there were still two minarets standing. Today, his description sounds like an epitaph:

No photograph, nor any description, can con- vey their colour of grape-blue with an azure bloom, or the intricate convolutions that make it so deep and luminous. On the bases, whose eight sides are supported by white marble panels carved with a baroque Kufic, yellow, white, olive green and rusty red min- gled with the two blues in a maze of flowers, arabesques and texts as fine as the pattern in a teacup .. . If the mosaic on the rest of the Musalla surpassed or even equalled what sur- vives today, there never was such a mosque before or since.

A baked brick stump is all that survives.

Previous page

Previous page