The good life and how it is to be lived

Christopher Bray

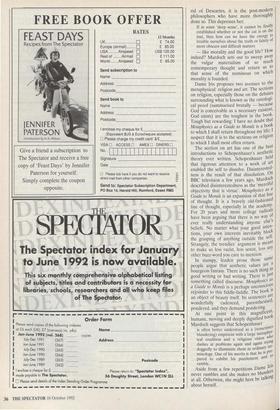

METAPHYSICS AS A GUIDE TO MORALS by Iris Murdoch Chatto, £20, pp. 520 Fans of the fictions of Dame Iris Murdoch should be warned that Meta- physics as a Guide to Morals is not her new novel. The book, which has its origins in the 1982 series of Gifford lectures she gave at Edinburgh University, is the magisterial piece of philosophy her output has forever unconsciously been promising. The press release claims it is an introduction to philosophical debate that is suitable for the general audience. I'm not sure it is as suitable as her wonderful book of Platonic dialogues, Acastos, but taking it at a leisurely pace the general reader will find much of immense and lasting worth here. Read rapidly the book takes on a surreal air. One leaps about from Kierkegaard to St Anselm, from Kant to Derrida, from Wittgenstein to Wittenberg (well, Shake- speare, anyway), all by way of the late Freddie Ayer. This is a book to be kept by the bedside and read a few pages a day. Even after two readings I cannot pretend to have taken it all in: Dame Iris's argument is a massive one, and paraphrase all but impossible.

The book's main theme, familiar from her many novels, is the good life and how it is to be lived. Murdoch wonders whether, in the post-modern world, all certainties gone, we can even agree on a single morality, let alone the existence of a greater being to watch us enact it.

Gide once said that personal responsibil- ity' increases as that of the gods decreases. One wonders what he would have made of Jean Baudrillard, the French post- modernist who last year questioned whether the Gulf War ever took place. He argued that in a world where most of our knowledge is filtered through the flickering haze of television, there is no way of ascertaining the truth. Newspapers and magazines are no more reliable. We can no longer trust language to deliver up the unvarnished truth. All we get is the varnish. The idea of the human individual is just that — an idea: we are all of us but by-products of language. We don't use language; language uses us. As Murdoch points out, while Sartre thought he had got rid of Descartes, it is the post-modern philosophers who have more thoroughly done so. This depresses her: If in some 'deep sense', it cannot be finally established whether or not the cat is on the mat, then how can we have the energy to trouble ourselves about the truth or falsity of more obscure and difficult matters — like morality and the good life? How indeed? Murdoch sets out to sweep away the vulgar materialism of so much contemporary thought and return us to that sense of the numinous on which morality is founded. Dame Iris proposes two avenues to the metaphysical: religion and art. The sections on religion, especially those on the debates surrounding what is known as the ontologi- cal proof (summarised brutally — because God is conceivable as a necessary existent, God exists) are the toughest in the book. Tough but rewarding: I have no doubt that Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals is a book to which I shall return throughout my life; I suspect that it is to the sections on religion to which I shall most often return. The section on art has one of the best introductions to Schopenhauer's aesthetic theory ever written. Schopenhauer held that rigorous attention to a work of art enabled the self to dissolve. Disinterested- ness is the result of that dissolution. On BBC television a few years ago, Murdoch described disinterestedness as the 'merciful objectivity that is virtue'. Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals is an expansion of that line of thought. It is a bravely old-fashioned line of thought, especially in the academY. For 20 years and more college radicals have been arguing that there is no way of ever really understanding anyone else s beliefs. No matter what your good inten- tions, your own interests inevitably block the grasping of anything outside the self. Strangely, the trendies' argument is meant to make us less racist, less sexist, less any other buzz-word you care to mention. In stumpy, leaden prose those same people argue that aesthetic values are a bourgeois fantasy. There is no such thing as good writing or bad writing. There is just something called discourse. Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals is a perhaps unconscious rejoinder to this fiddle-faddle. The book is an object of beauty itself. Its sentences are wonderfully cadenced, parenthesised, pondered, and they demand pondering. At one point in this magnificent, humane, moving and deeply dignified book Murdoch suggests that Schopenhauer is often better understood as a (sometimes blundering) empiricist with a large metaphys- ical erudition and a religious vision who dashes at problems again and again trYIng doggedly to illuminate them in ordinary ter- minology. One of his merits is that he IS Pre- pared to exhibit his puzzlement and to ramble. Aside from a few repetitions Dame Iris never rambles and she makes no blunders

all. Otherwise, she might here be talking about herself.

Previous page

Previous page