ARTS

Theatre 1

Brno spring

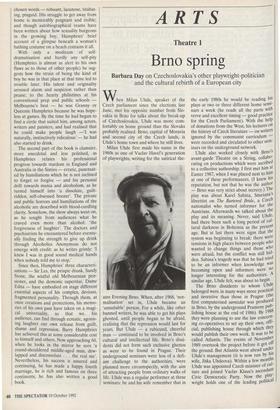

Barbara Day on Czechoslovakia's other playwright-politician and the cultural rebirth of a European city When Milan Uhde, speaker of the Czech parliament since the elections last June, met his opposite number from Slo- vakia in Brno for talks about the break-up of Czechoslovakia, Uhde was more com- fortably on home ground than the Slovaks probably realised. Brno, capital of Moravia and second city of the Czech lands, is Uhde's home town and where he still lives.

Milan Uhde first made his name in the 1960s as one of Vaclav Havel's generation of playwrights, writing for the satirical the- atre Evening Brno. When, after 1968, 'nor- malisation' set in, Uhde became an `unsuitable' person. For a while, like other banned writers, he was able to get his plays ghosted, until people began to be afraid, realising that the repression would last for years. But Uhde — a rubicund, cheerful man — continued to be involved in Brno's cultural and intellectual life. Brno's dissi- dents did not form such exclusive ghettos as were to be found in Prague. Their underground seminars were less of a defi- ant challenge to the authorities, were planned more circumspectly, with the aim of attracting people from ordinary walks of life. Uhde was a regular performer at these seminars: he and his wife remember that in

the early 1980s he would be reading his plays at two or three different home semi- nars a week (he reads all the parts with verve and excellent timing — good practice for the Czech Parliament). With the help of donations from the West, his lectures on the history of Czech literature — on writers ignored by the communist curriculum — were recorded and circulated to other sem- inars on the underground network. Uhde also worked closely with Brno's avant-garde Theatre on a String, collabo- rating on productions which were ascribed to a collective authorship. I first met him at Easter 1987, when I was placed next to him at one of these performances. (I knew his reputation, but not that he was the author — Brno was very strict about secrecy.) The play was about Karel Sabina, Smetana s librettist on The Bartered Bride, a Czech nationalist who turned informer for the Austrians. Afterwards we talked about the play and its meaning. Never, said Uhde, had there been such a long period of cul- tural darkness in Bohemia as the present age. But at last there were signs that the system was beginning to break: there were tensions in high places between people who wanted to change things and those who were afraid, but the conflict was still hid- den. Sabina's tragedy was that he had tried to be an informer when knowledge was becoming open and informers were no longer interesting for the authorities. A similar age, Uhde felt, was about to begin. The Brno dissidents to whom Uhde belonged were in many ways more practical and inventive than those in Prague (the first computerised samizdat was produced in Brno, by the underground Prameny pub' lishing house at the end of 1986). By 1988 they were planning to use the law concern- ing co-operatives to set up their own, offi- cial, publishing house through which they would publish their own work. It was to be called Atlantis. The events of November 1989 overtook the project before it got off the ground. But Atlantis went ahead under Uhde's management (it is now run by his wife, Jitka Uhdeova). Within a few months Uhde was appointed Czech minister of cul- ture and joined Vaclav Klaus's ascendant Civic Democratic Party. Now the play- wright holds one of the leading political

positions in the country.

This is not, as we know, an unprecedent- ed change of role in Czechoslovakia. More remarkable is the aplomb with which a true Bmak has commandeered an important position in Czech political life, normally dominated by born or adopted Pravaci. Uhde now seems to have the best of both worlds: power in the capital and the plea- sures of home life in Brno. For in summer Brno has the air of a southern city. Mor- avia is one of the loveliest and most fertile regions in Europe, its meadows stretching green even in the hottest days to blue hills and dark forests. Whilst shoppers in Prague pay high prices for their fruit, apri- cots fall from wayside trees in the Brno suburbs. When the Iron Curtain came down, Brno suffered two disasters: the loss of its German community (expelled before 1948, but at communist instigation) and the severance of its communication with Vien- na and the south. For the citizens of Brno and Vienna used to employ the same archi- tects to build their houses, the same musi- cians to play the same tunes zum Kaffee and Sachertorte, the same painters to paint the ceilings of their churches. Brno became a provincial city, stranded on the distant frontier of Moscow's empire.

Now it is rediscovering its cultural identi- ty. The city fathers sit in committee in the open air of a summer afternoon, figuring out policies for international co-operation. Austrians in evening dress drive up for per- formances in the Janacek Opera House Vienna is now easier for Brno citizens to reach than Prague, and a more stimulating centre than the tourist-ridden Golden City. Vienna can provide professional contacts, business partners and materials not yet available in the Czech lands.

The results of this are rapidly becoming visible. I live in a street of medium-sized residential blocks built between the wars, most of them having now been restored to their original owners. Between one tram stop and another, .a dozen new businesses have opened in the semi-basements — a sports shop, a hairdresser, a coffee shop. As I stepped from the tram a week or two ago, a new wine cellar virtually opened in front of me (unlike Bohemians, Moravians are big producers and consumers of wine). And these are not shabby, ramshackle busi- nesses: the style and often elegance of shop façades and interior decoration testify to proper investment.

In the city centre, in crowded Ceska or Masarykova, nearly every shop is being rebuilt. In Ceska there is a bookshop where

once, in separate rooms divided by cur- tains, you could ask to look at one book at

a time. Now it has opened up its original stairs and galleries, and shelves of books ready for browsing reach to the ceiling. Over the shop front is a new sign: Sarvic

84 Novotny — Established 1883'. That says a lot. Barvic & Novotny are ignoring the

unfortunate aberration of 40 years. Barvic & Novotny are selling the authors who

weren't published, authors read at secret seminars when 20 or 30 of us squeezed in one living-room. Barvic & Novotny are selling books published by Atlantis and a hundred other new publishers, Czech liter- ature hardly known for two generations — Pekar and Deml, Reynek and Cerny. On the shelves of best-sellers you can find Vaclav Havel's Summer Reflections. I'm looking forward now to reading the reflec- tions of Brno's own playwright-politician.

Barbara Day works for the Jan Hus Educa- tional Foundation in Brno.

Previous page

Previous page