Exhibitions 1

John Wonnacott (Agnew's, till 6 November)

An artist for Britain

Giles Auty

At the end of last year, I cited the example of John Wonnacott to promote the radical notion that to be a modern artist need not involve the slavish following of international artistic fashions. This will be news to many in Britain's art schools who have been brought up to believe that that is precisely what being a modern artist must involve, a regrettable view encour- aged in general by their tutors.

If I used the case of Wonnacott last year for what it symbolised, I return to him now simply for what he has been doing. His major exhibition at Agnew's (43 Old Bond Street, WI) is the result of five years' very hard work. In view of this I am delighted that a new painting I have singled out already for particular praise has just been bought by America's premier museum. It is a feature of the artist's work that it appears to be 'simply' about physical appearances, an artistic orientation which has been under non-stop intellectual assault for the past hundred years. Thus Cubism, about which I wrote last week, liked to point to the absurdity of the pictorial convention of a fixed single viewpoint and that of illusory space. Yet Cubism was really an artistic revolution of a conceptual rather than an optical kind. Try crossing a busy road while employing Cubist conventions of looking and you will end up squashed even flatter than the modernist picture plane to which Cubism finally gave rise.

The truth is we do not `see' better or more penetratingly by adopting Cubist con- ventions, because they are as much a prod- uct of pictorial memory as of sight. Thus we 'know' the back of a violin is different from its front even when confronted solely by the latter. On the other hand, the human race 'knew' that the leaves of famil- iar trees were simply green — except in autumn, of course — until John Constable first pointed out through his painting that leaves regularly reflect colours from the sky. The tradition of the Slade School, which John Wonnacott attended, centred on such visual investigation: what the eye sees rather than what the mind imagines. It is to this broad and exciting course that John Wonnacott has devoted a working life of roughly 30 years' duration. During those three decades he has witnessed just about every stylistic and conceptual art form pro- posed as being of primary importance and relevance, save only the one he practises: Abstract Expressionism, Hard-Edge, Colour-Field, Pop, Op, Minimalism, Con- ceptualism, Neo-Expressionism, Neo-Dada . . . on and on and on. Indeed, it is against a background of indifference or scorn from his fashionable peers that Wonnacott has forged his remarkable and uncompromis- ing body of work. It takes monumental patience and single-mindedness to con- struct paintings as huge and complex as `Refit, Devonport', a recent commission for the Imperial War Museum, or 'Sir Adam Thompson, Day', 1985, a portrait of the erstwhile chairman of British Caledonian set against the vast space of a working hangar at Gatwick airport.

To make works of this kind requires not just perseverance and pictorial intelligence of a high order, but an unflinching belief in the continuing relevance of the great tradi- tions of European realist painting. Regret- tably, those who come through our present art school system are unlikely to be able to cling to such belief under the sustained sneers of their tutors. This is why the re- establishment of at least one art school devoted to a straightforward training in tra- ditional skills should be a matter of nation- al cultural priority. This is the role the Royal Academy Schools could and should have continued to play. If you wonder why it has not, perhaps you need look no fur- ther than its parent body, dedicated now, in its Summer Exhibitions, to encouraging international modernist fashions of the most vapid kind. Having seen Wonnacott's show you may also be puzzled as to why he was not made an RA long ago. The answer reflects credit on no one. By contrast, he is widely recognised as an artist of rare ability by those in British art who genuinely pos- sess such talent themselves: the painter Lucian Freud, for example.

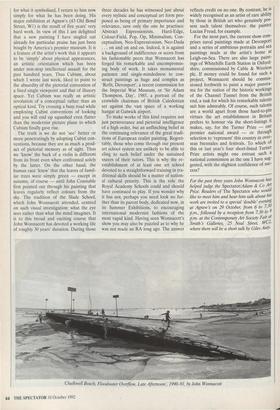

For the most part, the current show com- prises naval paintings made at Devonport and a series of ambitious portraits and sea paintings made at the artist's home at Leigh-on-Sea. There are also large paint- ings of Whitehills Earth Station in Oxford- shire, commissioned by Cable & Wireless plc. If money could be found for such a project, Wonnacott should be commis- sioned forthwith to paint a major panora- ma for the nation of the historic workings of the Channel Tunnel from the British end, a task for which his remarkable talents suit him admirably. Of course, such talents are a world apart from those hard-to-pin virtues the art establishment in Britain prefers to honour via the short-listings it makes, say, for the Turner Prize — our premier national award — or through selection to 'represent' this country in over- seas biennales and festivals. To which of this or last year's four short-listed Turner Prize artists might one entrust such a national commission as the one I have sug- gested, with the slightest confidence of suc- cess?

For the past three years John Wonnacott has helped judge the Spectator/Adam & Co Art Prize. Readers of The Spectator who would like to meet him and hear him talk about his work are invited to a special 'double' evening at Agnew's on 29 October, from 6 to 7.30 p.m., followed by a reception from 7.30 to 9 p.m. at the Contemporary Art Society Fair at Smith's Galleries, 25 Neal Street, WC2, where there will be a short talk by Giles Auty.

'Chalkwell Beach, Floodwater Overflow, Late Afternoon, 1990-91, by John Wonnacott

Previous page

Previous page