Belgrade begins

Raymond Keene

After game 11 the match was due to switch to Belgrade, but before that hap- pened there was a closing celebration in Sveti Stefan, at which the normally austere Fischer lightened up to the extent of playing five-minute games against the

press.

On switching to Belgrade, the Blue Hall of the Sava Centre to be precise, the match conditions changed somewhat. Instead of a giant glass bell, a huge glass screen was erected across the stage, much larger than the one in Sveti Stefan, apparently to insulate Fischer from disturbance, while Fischer also ordered the hall to have always at least 2,000 spectators present. In Belgrade, where the population is fanatical about chess, this was not a problem.

In spite of achieving perfect conditions Fischer was unable to find his form for game 12 and went down in flames, for Spassky's third win, when he failed to find the right plan in the opening.

Spassky — Fischer: 'World Championship Match,' Game 12, Belgrade, 1992; Kings Indian Defence.

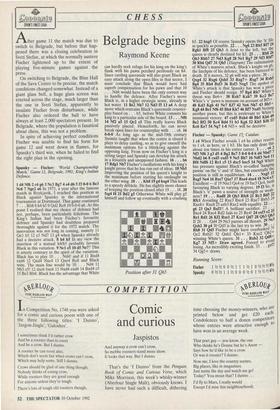

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 f3 0-0 6 Be3 Nc6 7 Nge2 a6 In 1973, a year after the famous match in Reykjavik, I reached this position as Black against Spassky in the international tournament at Dortmund. That game continued 7 . . . Rb8 8 h4 h5 9 0d2 Re8 10 0-0-0 a6. At this point I realised that my choice of defence had not, perhaps, been particularly felicitous. The King's Indian had been Fischer's favourite defence and Spassky had doubtless prepared thoroughly against it for the 1972 match. The innovation was not long in coming, namely 11 Qel b5 12 e5 Nd7 13 g4 when Spassky already had a decisive attack. 8 h4 h5 In my view the insertion of a mutual h4/h5 probably favours Black in this variation. 9 Ncl e5 10 d5 Ne7? This is utterly contrary to the spirit of the variation. Black has to play 10 . . . Nd4! and if 11 Bxd4 exd4 12 Qxd4 Nxe4 13 Qxe4 Re8 and Black wins. The main line would be 10 . . . Nd4 11 Nb3 c5! 12 dxc6 bxc6 13 Nxd4 exd4 14 Bxd4 c5 15 Be3 Rb8. Black has the advantage that White can hardly seek refuge for his king on the king's flank with his pawn perched perilously on h4. Since castling queenside will also grant Black an easy attack along the open files in that sector, I must conclude that Black would have had superb compensation for his pawn and that 10 . . . Nd4 would have been the only correct way to handle the defence. After Fischer's move Black is, in a higher strategic sense, already in hot water. 11 Be2 Nh7 12 Nd3 f5 13 a4 A deep move which restrains Black's queenside counter- play based on . . . b5, before White commits his king to a particular side of the board. 13 . . . Nf6 14 Nf2 a5 15 Qc2 c5 This really leaves Black passively placed. Henceforth, he can never break open lines for counterplay with . . . c6. 16 0-0-0 As long ago as the mid-19th century Steinitz taught that when the centre is closed it plays to delay castling, so as to give oneself the maximum options for a blitzkrieg against the opposing king. From now on Fischer's king is a sitting target and Spassky can develop his attack in a leisurely and unopposed fashion. 16 . . . b6 17 Rdgl Nh7 Fischer's oscillations with his king's knight prove that he has run out of ideas. 18 N135 Improving the position of his queen's knight to the maximum before starting his onslaught on the other wing. 18 . . . Kh8 19 g4 hxg4 This leads to a speedy debacle. He has slightly more chance of keeping the position closed after 19 . . . f4. 20 fxg4 f4 21 Bd2 g5 Otherwise White will play g5 himself and follow up eventually with a crushing Position after 31 Qh5 h5. 22 hxg5 Of course Spassky opens the 'h' file as quickly as possible. 22 . . . Ng6 23 Rh5 Rf7 24 Rghl BIB 25 Qb3 A feint to the left, but the queen is clearly destined for h3. 25 . . . Rb8 26 Qh3 Rbb7 27 Nd3 Kg8 28 Nel Rg7 29 Nf3 Rbf7 30 Rh6 Qd7 31 Qh5 (Diagram) The culmination of White's massive attack. Black's knight on g6, the linchpin of his defence, has been battered to death. If it moves, 32 g6 will win a piece. 31 . • • Qxg4 32 Rxg6 QxhS 33 Rxg7+ Rxg7 34 Rx1I5 Bg4 35 Rh4 Bxf3 36 Bxf3 Nxg5 The upshot of White's attack is that Spassky has won a piece and Fischer should resign. 37 Bg4 Rh7 White's threat was Be6+. 38 Rxh7 Kxh7 39 Kc2 Bel White's `e' pawn is immune on account of Bf5+ • 40 Kd3 Kg6 41 Nc7 Kf7 42 Ne6 Nh7 43 Bh5+ Kg8 44 Bel Nf6 45 Bh4 Kh7 46 Bf7 Nxd5 Netting another pawn, but this is irrelevant to White's imminent victory. 47 cxd5 Bxh4 48 Bh5 Kh6 49 Be2 Bf2 50 Kc4 Bd4 51 b3 Kg6 52 Kb5 Kf6 53 Kc6 Ke7 54 Ng7 1-0 Nf5+ will be decisive.

Fischer — Spassky: Game 15; Catalan. 1 c4 When Fischer avoids 1 e4 he either resorts to 1 c4, as here, or 1 b3. He has only done this about ten times in his entire career. 1 . • _! .e6 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 g3 d5 4 Bg2 Be7 5 0-0 0-0 6 d4 NMI„ Nbd2 b6 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Ne5 Bbl 10 Ndf3 Ne4 11 Bf4 Ndf6 12 Rcl c5 13 dxc5 bxc5 14 Ng5 White has pressure against Black's so-called 'hanging pawns' on the 'c' and 'd' files, but essentially the position is still in equilibrium. 14 . • Nxg5 15 BxgS Ne4 16 Bxe7 Qxe7 17 Bxe4 dxe4 18 Nc4 c3! Excellent — if 19 Nxe3 Qe4 or 19 fxe3 Qe4, both favouring Black to varying degrees. 19 f3 So, is Black's `e' pawn a source of strength or weak- ness? 19 . . . Rad8 20 Qb3 Rfe8 21 Rc3 Bd5 22 Rfcl Avoiding 22 Rxe3 Bxc4 23 Rxe7 Bxb3 24 Rxe8+ Rxe8 25 axb3 Rxe2 with equality. 22 . • • g6 23 Qa3 Bxf3!! A brilliant sacrifice. 23 Bxc4 24 Rxc4 Rd2 fails to 25 Re4! 24 exf3 e2 2', Rel Rdl 26 K12 Rxel 27 Kxel Qd7 28 Qb3 Qh-' If 28 . . . Qd4 29 Ne3 parries all threats. 29 Ne3 Qxh2 30 g4 30 Qd5 is the last try to win. 30 • • ' Rb8 31 Qd5 Fischer might have overlooked 31 Qc2 Rxb2! 32 Qxb2 Ohl + 33 Kxe2 Oh2+ winning White's queen. 31 . . . Rxb2 32 Qd8+ Kg7 33 Nf5+ Draw agreed. Forced to avoid losing. An incredibly exciting finish. 33 . • • gxf5 34 Qg5+ draws.

Running Score: Fischer 1 1/2 1/2 0 0th I 1 1 1/2 1 0t/ 1/2 1/2 81/2 Spassky

0 1/2 1/2 1 1 1/2 0 0 0

1/2 0 1 11 1/2 61/2

Previous page

Previous page