TOPICS OF THE DAY.

ROYAL MARRIAGE-SETTLEMENTS.

WHILE persons are found obnoxious to the penalties of treason for "levying war" against the Sovereign—while many families, it is to be feared, are in a state of absolute want of food—and while nearly the whole of the disaffected masses are exposed to the se- verest privations—political quidnunes, who, like the BOURBON Princess, would substitute piecrust for bread, are occupied in spe- culating upon the probable amount of the " allowance" intended for the Queen's husband. Some say it is to be 100,000/. a year, on an alleged precedent left by the last of the &mars; others say that 50,000/. is to be the sum; others, on a story going the rounds, say that the Duke of WELsesotoss has settled that 30,000/. is enough. Drawing the distinction between Prince ALBERT as the husband qt. the Queen and Prince ALBERT as a widower, we may observe, that in the latter event few would care for granting less, but there could be no reason for granting snore, than an allowance equal to that of a Duke of the Blood Royal. As the husband of the Queen, if the various bearings of the question be calmly ex- amined it would appear that 'nothing is requisite in the nature of the case, or can be prudently granted in the circumstances of the times or the temper of the people. With regard to necessity, no one will pretend that Prince AL- BERT can require an income during the Queen's life. A Civil List has been granted her, 10,000/. more than that which sufficed for the most luxurious of Kings., when the value of money was less, and the price of all commodities much greater, rendering Queen VICTORIA'S 395,000/. a year equivalent to 600,000/. in Gemara: the Fourth's time. If the grant of 50,000/. a sear for the Privy Purse of Queen ADELAIDE be relied on, it is answered that the Queen Consort is a political person recognized by the constitution ; re- quired to have great officers of her household, and to keep up a public state for public purposes ; amenable to the law, and, in a case which need not be particularized,. specially amenable with her head. But the husband of the Queen is a political nobody, without any British entity whatever; for n«turatization makes him a subject, and it requires particular Acts 0' Parlia- ment to bestow upon him either status or functions. Even were this argument wanting, the custom of the country is not without force, (for national customs have a concealed influence upon despotism itself) : it is usual for husbands to make settlements upon their wives, but not so usual, in well-assorted matches, for wives to snake settlements upon their husbands. Still less, when a man is lucky enough to captivate an heiress, does that heiress apply to other parties to provide an income for her lover. In snatches where both parties have means, it is not, indeed, un- common to have a sort of joint-stock settlement, with benefit of survivorship, and a remainder to the children : but this is an in- stance that does not apply to Prince ALBERT.

On the morality of the matter, or its probable effects upon the

future domestic happiness of the Queen, we need not enlarge. The opinion—or more properly, perhaps, the conscience—of this country is against any separate establishment for man and wife ; and the practice does not obtain amongst the very highest of our nobility, if respectable. The looseness of the marriage-tie and of sexual morality in German estimation, is notorious, and remarked by every traveller. To give to a Prince, unaccustomed to money, and in the very heyday of his blood, an allowance double or quad- ruple that of tut English Royal Duke, and more at the lowest esti- mate than was granted to the late King when a married man and heir presumptive to the throne, would be suggesting a temptation

to irregularities, whilst it furnished hint alike with the means and the opportunities for their indulgence. And if he is to live with his wife, will not this income suffice them ?

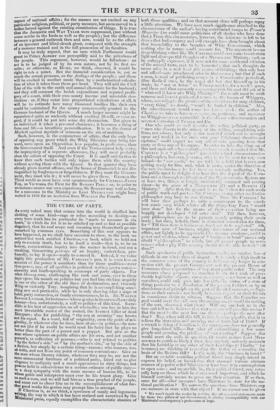

Per annum.

PRIVY PERSE, e. pocket-money) £00,000 SALAnu:s OF TI1E HOUSEHOLD, (i.e. nlaries of the Great Officers of State and their subordinates, with the pay of the servants of varion,, kinds) , 131,200 EXPENSES OF THE HOUSEHOLD, (i. e. tradesmen's bills for eating, drinking, and equipage—in other words, the cost of the chambers, the kitchen, the cellar, and the stable) 172,500 ROYAL BOUNTY, ALMS, AND SeEetat, SERVICE, (a sum to spend no diserainn) 23,200 UNAPPROPRIATED MONIES, (ditto) 8,040

£395,000

here is surely sufficient for any station, especially when a husband creates no additional establishment, and causes in fact no additional expense. If a sepnrate income should not, as its probable ceurse, lead to irregularities and dissipation, it will in- duce the recipient to snake a purse for his German relatives—as has been done before with English taxes, and will give rise to a parcel of offices for the " No-Patronage Government," which may also serve as a means for future backstairs intrigue. If the Whigs bring forward a "liberal" provision for Prince ALBERT, a disposi- tion to truckle for Court favour will not be their only reason : they will reckon upon receiving back a share of it in places for clients. In the event of removal front responsible office, it will also enable them to occupy a position in the enemy's cabinet, checking or baffling him at every turn, but which no Minister can constitu- tionally remove, because the intriguers will have no constitutional function. If the Whigs are allowed to manage this, it will be the neatest thing they have done yet, and better adapted to "keep

out the Tories," or any other party, than their majority—if thel have one.

It has been put about so widely as to obtain pretty general ere. dence, that a separate allowance of 100,000/. a year was grant

to Prince GEORGE of Denmark, husband of Queen ANNE. The case of Prince GEORGE is not at all to the purpose. In 1689,

an address to the Crown to snake a provision for the " Prins

and Princess Anne of Denmark " was agreed to by the Gess

mons, after two days' debate ; a patent the Princess held frou the Crown (before the Revolutioti) being annulled. On her at

cession, in 1702, Queen ANNE sent a message to Parliament,

porting—" That her Majesty, considering that there was but a very small provision made for the Prince her husband, Wile should

survive her, and that she was restrained from increasing the sue

by the late act of Parliament for settling her revenue, thought it necessary to recommend a further provision for the Prince to tha consideration." Upon this a grant of 100,0001. a year was made to the Prince in case lie survived the Queen ; which, froin his greater age, and an infliction of asthmatic disease, was not es.

'meted; nor did it happen, Prince GEORGE dying before his wife. The precedent, therefiwe, is directly in favour of our argument that nothing is requisite during the life of the Quasi. But if a precedent existed it would be of little value; for there is no res precedent where there is no real analogy. So fiur as the first grant of 50,000/. a year, and the subsequent contingent provision of 100,000/. to the Prince, were obtained by the two great fitetions bidding against each other !Or Court favour at the ublic cost, there may be some resemblance ; but here it ends. Whatever we may thiuk now, ANsin in popular idea had served the nation contributing to the Revolution ; so had her husband. As one of the speakers said in the debate, " she forsook her father for the Protestant religious." The state of Denmark, though not of the first European class, was more important then than now, end pee sesseds what it still possesses, an IliStOliC Mlle- A Soli of its royai. house had a natural claim for a liberal allowance, if an allowance had been inside at all. Denmark too could render us service in time of need : " Shall we not confirm time patent," said Sir Wnirss Gowen,

"110W we have i 0,C00 Danes sent over to fight for us?" But we should look in vain tbr this kind of assistance ftom Prince

ALIIERT'S fondly. A Bedchamber-woman will hardly assert that either dignity or safety is added to the Imperial Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, both the Indies, and sundry regions in America, Africa, end Australasia, by an alliance with the lucky family of Saxe Coburg. But if courtly or political precedents existed, and were closer, their weight would be little, for the whole system of' life is cheesed. The people then were fewer, and scattered ; there was no facility of' locomotion—they could neither communicate with each other nor reach the Metropolis without a tedious pilgrimage ; the half- ' enlightened and disaffected swarms of the great manufficturing hives were not called into being ; the National Debt was trifling; jOUP11101:11/ NVtIS in its cradle, and public opinion very feeble. What a court fiction could do with safety then, many not be ventured now. The influences of' public opinion, too, were not so adverse as in our time to stately etiquette, to the tom mat pageantries it involves, and to separate maim& nnuces fbr though feudalism was extinct, its , notions remained ; and one of' the fbremost of them required a sacrifice of individual wishes to the necessities of the individuara position. The lord, high or low, claimed an absolute power in the disposal of the hand of his orphan vassal ; tiot in the first instance from mere tyranny, but beeau.e Iii s Ian d was granted on the tenure of military service, and it was neccsHiry that his dependent should not marry a per:-..on unable to serve, or perhaps an enemy. A "%SNOW, if nominally free, was compelled to choose a 'husband who could protect her ; for otherwise her lands would be ravaged, her place besieged, and her person become the prey of the first neighbour strong enough to attack her. The powers of the feudal lord de. scended to parents, who then, and till within these hundred years or less, overbore the wishes of their children as a matter of course. In this condition of societ3 may be found sonic explanation of as moral corruption, to which a rigid but polished etiquette and formality gave an outward show whilst it facilitated an interior licence. The Continental princes are still frequently exposed to this sacrifice of feeling to political necessity ; which may, if' not excusably, explain the reputed libertinism of foreign manners. And when these constraints are put upon the will, separate house- holds and their consequences may be mama' enough. The Sove- reign of' this country is indeed restrained by law, as the generality of her Protestant subjects are restrained by opinion or prudence, from marrying a Roman Catholic, But the most courtly Whig will scarcely pretend that Queen VICTORIA has, for the public weal, aeo constrained her wishes in marrying Prince ALBERT, and the public ought to be called upon to maintain hint in separate state. Nor do the condition and temper of the times warrant it. The public income is considerably below the expenditure, with small signs of increase. The prediction we made on the first proposal of time lavish Whig Civil List is in course of fulfilment : one great "grievance," which Welsh Chartism revolted against, was the cost of' the Court, and of officers (some incorrectly) assumed to belong to the Court. Is it wise, is it safe, to add to this exasperation, for a man whom the masses will not regard with favour as a foreigner, and whom demagogues can holdup to them as a German adventurer and fortune- hunter ? Never since the outbreak of the serfs in the middle ages, producing the wars of the Jacquerie in France and the insurrection under WAT TYLER in England, has there been a snore troubled

aspect of national affairs; for the masses are not excited on any particular religious, political, m or party measure, but see moved to a sullen hatred against the existing constitution of things. It is true that the Jacquerie and WAT YLER were suppressed, (not without sonic scathe to the lords as well as the people); but the difference between a general outbreak then and now, would be as the efforts of an ignorant and blind-drunk giant, compared with the strength of a monster trained and in the full possession of its fiteulties.

It may be truly argued, that no sum which Parliament would grant to Prince ALBERT can perceptibly add to the privations of the people. This argument, however, would be fallacious : an act is to be judged of by its own nature, not by its first re- sults; or otherwise, as lluain, we think, observes, it would be right to rob a miser. But the financial consideration is, not so much the actual pressure, as the feelings of the people ; and these will be escited in another mode than by a mathematical calcula- tion of what it takes from them per head. They will add the Civil List of the wife to the outfit and annual allowance for the husband; and they will contrast the lavish expenditure and reputed profli- gacy of a court, with their own scanty income and miserable des- titution or, if they enter into proportional calculations at all, it will be to estimate how many thousand fatuities like their own could be maintained for the money unnecessarily granted to the German husband of the Queen. A much larger amount might be squandered quite as uselessly without exciting or even re- gard, if it could be put into sonic thy abstraction. But given to an individual it takes a personal character; it becomes it thing of form and life—a breathing personification. It is as the drama of Macbeth against myriads of sermons on the sin of ambition. Such, however, is the conjuncture of laths, that the only hope of opposing any grant which the Whig Ministers may bring tbr- ward, rests 'moo an Opposition less popular, in professions, than the Government itself: And even if the Tories cannot help seeing the impropriety of a separate allowance, they will most prebably shun the odium of opposing the Court. It is small satistliction to know that such- tactics- will only injure them...with the country without serving them with the Omen. In that quarter they have already given mortal offence, and the house of Brunswick is not dis- tinguished by forgiveness or fbrgetfulness. If they want the Govern-

ment, they must win it ; it will never be given them. GEORGE the Third would as soon have sent spontaneously for Cuaiii.r.s JAMES

Fox, as VICTORIA the First far Sir RoBERT PEEL : or, to point to an instance nearer our own experience, Sir Ronear may wait as long foie a summons to the :Ministry as Lord Mia.ner RN le might have waited in 1835 for an incitation from WILLIAA1 the Fourth.

Previous page

Previous page