IRRESOLUTION ON LITHUANIA

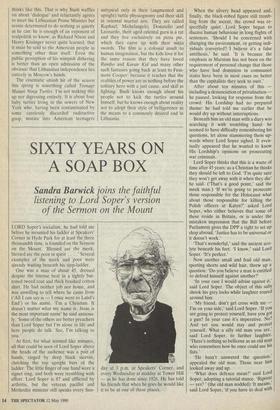

James Bowman reports that

President Bush's `wimpish' attitude is at odds with much of American opinion

Washington WHEN Mrs Prunskiene, the Lithuanian Prime Minister, came to Washington last week she received rather cold hospitality from the Bush White House. Treated as a Private visitor, she had to stop her hired car at the gate, show her Soviet passport and then walk up the drive alone. It has been suggested that Bush only agreed to see her in the first place because he was afraid of being upstaged by the receptions in her honour already arranged on Capitol Hill — at which, it turned out, she was given a rather warmer welcome. This is natural. The message she had to deliver here was much more congenial to the 535 shadow secretaries of state in the Congress than it was to those who actually have the responsibility for US foreign policy. It was that we did not have to choose between Gorbachev and Lithua- nian independence. Strong support for the latter would, in fact, help the process of perestroika in the Soviet Union. Since foreign policy to a congressman is largely an opportunity to strike moral attitudes, especially if there is any significant ethnic Population back home in the district sport- ing the relevant national colours, this was just what most congressmen wanted to hear.

The criticism that George Bush has been receiving over Lithuania is of no great immediate concern but the long-term effects may be more damaging to him. For the time being, the right wing has nowhere else to go; but the President has never been considered by Reagan Republicans as one of their own, and sniping from the right has been a recurrent feature of his presidency. The word 'wimp' — partly because it is presumed by the beefy boys of the Amer- ican heartland to apply naturally to effete, quiche-eating, Ivy League types like Bush — has been dusted off again in connection with the administration's failure to take advantage of the failed coup in Panama last October and its 'kowtowing' to the Chinese government in the wake of the Tiananmen Square massacre.

Nor is it just his foreign policy which is making the Republican true believers un- happy with their president. Many have

criticised what they see as his pandering to the environmentalists over clean air legisla- tion, his refusal to take a firm enough stand against obscene art which has been subsi- dised by the National Endowment for the Arts and his inviting homosexual leaders to the White House for the signing of new legislation against 'hate crimes'.

Now, and more prominently than in any of the earlier cases, the din of criticism of Bush's handling of Lithuanian indepen- dence is making itself heard. Patrick Buchanan, the bell-wether of the trium- phalist Right, is ding-donging away for all he's worth:

Lithuania decided the time was right to risk all; she stood up, lonely and brave; all she asked of the Great Republic was that we recognise her. Our response was to turn our back, and, with fine impartiality, call upon both victim and rapist to show 'restraint' . . . Americans are a moral people. They will not sustain a foreign policy rooted in a cold pragmatism that averts its gaze from the tragedy of a little country, to maintain cordial relations with its oppressor.

Take that, George Bush!

Yet this is not altogether what it seems: the last hurrah of the anti-communist Right, strapping on its not very rusty armour one last time to do battle with the renegade Bush and his new friends in the Kremlin. You can tell by the fact that some of the loudest anti-Bush rhetoric is coming from the Democrats. The party, since Vietnam, of a kind of curious, one-world isolationism has discovered, rather late in the day, the joys of Commie-bashing. Buchanan provides the key to understand- ing it when he writes, ominously, that 'Americans are a moral people'. Oh dear, oh dear! So they are. Sometimes one forgets these things.

For what we are really witnessing here is the same old conflict which has bedevilled American foreign policy for as long as there has been one: that between realpoli- . tik and evangelism. The Left and Right are now united in seeing the communist col- lapse as an excuse for (if not the consequ- ence of!) a crusade for American values economic freedom, democracy, national autonomy — in the territory of the former empire. Reagan might have made a good crusader for these days — though I suspect he was more of a realpolitiker than people give him credit for being — but Bush is left/right, or right/left, in the middle: a state department kind of guy who wants to advance American interests as an exercise independent of spreading the American gospel.

So at his press conference last Thursday Bush was asked: 'Why have you decided for Gorbachev rather than speaking out for American principle? (And, by the way, when did you stop beating your wife?) 'I don't think that's the choice,' he replied.

American policy wasn't to choose one or the other but to promote Soviet/Lithuanian 'dialogue' — a word which resurfaced in reply to a question about Latvia. That sounds like a fudge to American zealots like William Safire, who earlier last week published an imaginary message to 'the secessionary colonists in America' about their 'untimely and provocative declaration of independence' from the British:

Although King George III has his shortcom- ings in the economic sphere, your 'tea party'

in Boston Harbour was a sensationalist and unfair derogation of his tax policy. He is a force for stability and order at a terribly turbulent time. We happen to know that his court at St James's Palace contains more than a few 'hard linings'. The redcoat gener- als are restive. If these sinister forces gain the upper hand in the struggle for power, latent English national feelings will be ignited and the full force of the empire's irritation will be directed against your legitimate aspirations.

All of the American political mythology comes into play here: we know in our bones that plucky little nations struggling to free themselves from big empires are deserving of all support because that's the way we began. The relative practicalities of the glorious American and the prospective Lithuanian wars for independence are meant to weigh as nothing where principle is at stake.

And it is not just the right wing that thinks like this. That is why Bush waffles on about 'dialogue' and reluctantly agrees to meet the Lithuanian Prime Minister but seems determined to do nothing as quietly as he can: he is enough of an exponent of realpolitik to know, as Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger never quite learned, that it must be sold to the American people as something other than itself. Even the public perception of his wimpish dithering is better than an open admission of the obvious: that Lithuanian independence lies entirely in Moscow's hands.

The cinematic smash hit of the season this spring is something called Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. I'm not making this up nor digressing entirely. It is about four baby turtles living in the sewers of New York who, having been contaminated by some carelessly discarded radioactive goop, mutate into American teenagers untypical only in their (augmented and upright) turtle physiognomy and their skill in oriental martial arts. They are called Raphael, Michelangelo, Donatello and Leonardo, their aged oriental guru is a rat and they live exclusively on pizza pie, which they carve up with their ninja swords. The film is a colossal insult to human imagination, but the kids love it for the same reason that they have loved Rambo and Karate Kid and many other such fantasies going back at least to Feni- more Cooper: because it teaches that the realities of power are as nothing before the solitary hero with a just cause, and skill in fighting. Bush knows enough about his people not to kick the turtles around himself, but he knows enough about reality not to adopt their style of belligerence as the means to a commonly desired end in Lithuania.

Previous page

Previous page