JAPANESE SPECIAL

Far East of Eton

Murray and Jenny Sayle

either of us is, strictly speaking, an expert on the newly fashionable topic of education in Japan. Your genuine pundit should, at the least, have had some or all of his or her formal education in Japan, speak the language without accent, be deeply versed in the civilisation it expresses and be at the same time fluent in another language and well acquainted with its ideas and outlook, for the essential purposes of comparison.

We adult Sayles simply don't qualify. In fact, we only know each other's education- al background by repute, and occasionally by results. One of us (pure) was educated, more or less, at Erskineville Opportunity Class, Canterbury Boys' High and the University of Sydney, the other (mere) admirably at Woodford, Essex Girls' High and l'Universite de Nantes. One of us knows the Japanese system only as a parent (which, in Japan still means a fairly high level of involvement) and, in Jenny's case, as an occasional teacher and partici- pant.

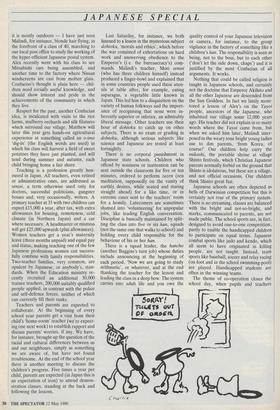

We have, however, three full-time ex- perts in the house, well qualified to fill the blanks in our knowledge. Alexander (named for the Macedonian miilitary man and the better known former editor of this magazine), 11, is a sixth-grader at our local village primary school. His sister Malindi, nine, is in third grade. Their brother Matthew, pushing four, attends the local Infants' school. Both these establishments are part of the ordinary, 'free' tax-funded Japanese state-run system, and their class- mates are the children of our neighbours, ranging from those of the richest family in the village (who own the textile mill) through those of our doctor and dentist to the families of local rice farmers and factory workers. The language of instruc- tion is, of course, Japanese. Our children were all born here in Aikawa-Cho, whose name, appropriately, means 'Love River Town'.

In recent years one or two Korean or Vietnamese children have been enrolled, but ours are the only blue-eyed, fair-haired youngsters who have ever attended our local schools, or, for that matter, the only ones their schoolfriends have ever seen in the flesh. We would like to report, straight off, that none of us has ever encountered any racism in the Japanese school system and that, on the contrary, teachers and neighbours have gone to considerable lengths to make our offspring feel wel- come. Evidence: our daughter completed three years of kindergarten without ever having heard the word gaijin (outside person, foreigner). We asked her how she was referred to: 'as Alex's little sister, of course' she replied scornfully.

We should perhaps also explain here that we speak English at home, read Winnie the Pooh and Skippy the Kangaroo to our children, and that all three of them speak rather posh English, the influence, their father believes, of their mother. We are nevertheless living in deepest rural Japan, with many aspects of life, including the educational system, very different from the ones we knew. A sample day will perhaps bring out some differences.

Our day begins, summer and winter, at 6.30 a.m. School is six days a week, Saturday a half-day, with school activities from time to time on Sundays as well. On the equivalent of high days and holidays the sing-song bonging of a Shinto gong in the shrine next door will sometimes beat our trusty Japanese alarm clocks to the call. Breakfast is at seven, Japanese-style, which these days can be anything from rice and fish to toast, bacon and eggs (all firm favourites).

At 7.40 the group of children who will walk to school together is noisily gathering at our door. Walking to school is obliga- tory, part of the process of socialisation which is, of course, the central purpose of education. The obligation is reciprocal: the Japanese state has to provide a primary school within walking distance of every rate-paying habitation. There are schools in remote places with five or six pupils.

The walking group, up to eight, is in the

JAPANESE SPECIAL

charge of the oldest child who carries a flag and is held responsible for getting the rest to school on time, in principle 8.10, at the latest 8.25 a.m. The group waits outside one's door, cheerfully insistent, and occa- sionally the leader will, with parental permission, invade a house to drag slug- gards out — but this is rare, peer group pressure normally being quite enough. For the past five years Alexander, an under- the-covers reader on scientific and literary topics and so a slow riser has frequently needed a call of Sayru-kun! (an affection- ate diminutive, along the lines of 'old chap!') to get him moving. This year he is the group leader and a lad transformed, impatient to get on the road with his sister, who is now part of his responsibility. He still, however, reads under the covers.

Here we see the first inculcation of key Japanese principles: flag-carrying, meticu- lous organisation, reciprocal responsibility and the self-policing of groups. The indi- vidual right, if there is such a thing, to travel by car is extinguished in favour of the higher interest in getting a group to function smoothly towards a common and, of course, externally mandated purpose. This sounds rigid, perhaps, but the system is softened by many humane and admirable touches. Handicapped children with Down's syndrome, crippled limbs and other afflictions are kept in the system on an equal footing with the others as long as possible, which includes the compulsory walk if they are physically up to it, and the friendships thus formed visibly enrich both sides. Alexander, for instance, has a par- ticular, spontaneous friendship with just such a courageous brain-damaged boy.

Mutual help on the village level is evidenced in many ways. Our village is in the mountains and we can easily get a foot or so of snow overnight. In principle, parents are responsible for keeping a path clear for the walk to school, and the village chief (an informally-elected, unpaid, Buggins's-turn job) telephones the night before, warning that parents should be ready at 6.30 a.m., shovel in hand, if the Town Hall announces over the village loudspeaker system that school is open for the day. Total suspension of lessons is very rare. What happens if a parent fails to turn out? Solicitous neighbours would call with hot food, assuming an illness in the house- hold. Good neighbourliness, taken for granted, is a mighty motivator.

The school building and playground are spartan but adequate, of a pattern uniform throughout Japan. On Mondays and Fri- days there is a general school assembly, with some inspirational remarks by the headmaster. Some schools bow to the national and school flags on these days. Ours does not, but we would have no objection if they did. No other saluting or pledging allegiance is called for, and our neighbours don't see any point in such exercises — as another parent once told us, 'We don't really need to remind our children which country they're in.'

The periods of instruction are 45 minutes each, with intervals in the playground to blow off steam. Classes are currently lim- ited to 40 maximum, a number which has gradually fallen with Japan's birthrate in the past two prosperous decades. It will probably be 30 to 35 a decade hence. The curriculum is set by the Education Ministry in Tokyo with little room for school or teacher variation, another rigidity which has certain advantages — on a given day every schoolchild in Japan will be studying much the same thing, so that a flourishing monthly children's newspaper and maga- zine, commercially published, are able to feature articles on the science subjects of the month and stories which introduce the new Chinese characters the children have just learnt. The magazine comes with such useful giveaways as small plastic micro- scopes, test tubes and ant colonies.

The study of Japanese (the schools call it kokugo — 'national language') takes up six periods a week, the same as mathematics. Of these two pillars of the system Japanese is for us by far the more daunting. A mixture of some 10,000 basic Chinese characters, all different, many more com- pounds, two Japanese-invented syllabaries of 72 letters each and our own footling ABCs, the Japanese writing system has been defined as 'the greatest barrier to human communication ever devised by the mind of man'. Children have to master 996 characters by the end of primary school, 1,945 by matriculation, 3,000 to be consi- dered passably literate.

We ignorant foreign parents try, in our cunning adult way, tricks and witty mne- monics to remember, say, the 19 strokes with which ai, the 'love' in our own postal address, is written, and in which order this bit looks like a leaky roof, that part is dripping tears, and the whole emotion rests on bun, 'knowledge' (that's a laugh). 'Sit cross-legged, hand on heart' advises another rather condescending memory

settled for a quiet weekend in Bournemouth' we 'So

guide for foreigners. But as fast as we get one section right, another dissolves into the mist. 'No, Mummy', advises Malindi, a straight-A student, over the kitchen table, 'You just have to get them into your head!' Japanese schools employ no flash cards, language laboratories, visual aids or other high-tech would-be short-cuts. The poor little devils just have to learn them. One's admiration for one's children, another important function of education, can only grow.

Is it worth 250 hours a year for 12 years, with copious homework, just to read and write? This is a question we are often asked, and ask ourselves. The script is of course the rocky road into Japanese cul- ture and beyond to its parent, the majestic civilisation of China. It is said to improve a child's visual imagination, if he or she has some to begin with. The characters are certainly elegant, especially after the 50 additional hours a year devoted to calligra- phy with brush and ink, and once mastered they are read as effortlessly as, we hope, you are reading this. We are inclined to view them as the Asian equivalent of cricket — good exercise (for the mind) and, through mastery of an esoteric set of rules, the pass to a world-wide community. The truth they teach, however, is not, at least conventionally, so sporting: that no- thing of value is to be had without hard, sustained, step-by-step work.

After this mental Everest, mathematics are, relatively speaking, child's play. Prog- ress is fast with six hours a week and both algebra and geometry begin in the fifth grade. Great stress is placed on pencil-and- paper numeracy. Calculators are barred, although the centuries-old counting-frame (soroban) is introduced to help visualise big numbers — and, with a budget in the trillions of yen, Japanese numbers get very big. One result is a saucy Japanese inven- tion, the electronic calculator with built-in soroban to check the machine's results.

Science (three hours a week) is taught imaginatively with experiments in electric- ity, magnetism, compressed gases and so on. Home-making gets two hours a week, and, the classes being mixed, Alexander has sewn a rucksack and an apron and cooked omelettes, hotcakes and potato chips well up to his sister's standard. Art (two hours) is the usual drawing, painting and model-building. The music-room (two hours) is the best-equipped in the school, with a Yamaha organ for each student and portraits of 30 composers, all Europeans. The theories of Shin'ichi Suzuki on early musical training are followed, and our older children have both played the piano in public to the restrained enthusiasm of Japanese audiences.

Social studies (three hours a week) get equal attention. This is a popular subject as

JAPANESE SPECIAL

it is mostly outdoors — I have just seen Malindi, for instance, blonde hair flying, in the forefront of a class of 40, marching to our local post office to study the working of the hyper-efficient Japanese postal system. Alex recently went with his class to see Mitsubishi cars being assembled, and another time to the factory where Nissan windscreens are cast from molten glass. Confucius's thought is plain here — chil- dren need socially useful knowledge, and should show interest and pride in the achievements of the community in which they live.

Respect for the past, another Confucian idea, is inculcated with visits to the rice farms, mulberry orchards and silk filatures which surround our village. Matthew will later this year gets hands-on agricultural experience at something called an o-imo `dig-in' (the English words are used) in which his class will harvest a field of sweet potatoes they have just planted, and will tend during summer and autumn, each child bringing home a fair share.

Teaching is a profession greatly hon- oured in Japan. All teachers, even retired or administrative ones, are addressed as sensei, a term otherwise used only for doctors, successful politicians, gangster bosses and, very occasionally, writers. A primary teacher at 35 with two children can expect £15,000 a year, after tax, with extra allowances for housing, remoteness, cold climate (in Northern Japan) and a car where necessary. A headmaster or mistress will get £25,000 upwards (plus allowances). Women teachers get a year's maternity leave (three months unpaid) and equal pay and status, making teaching one of the few Japanese professions women can success- fully combine with family responsibilities. Two-teacher families, very common, are opulent by Japanese, or anybody's, stan- dards. When the Education ministry re- cently recruited an additional 30,000 trainee teachers, 200,000 suitably qualified people applied, in contrast with the police and self-defence forces, neither of which can currently fill their ranks.

Teachers and parents are expected to collaborate. At the beginning of every school year parents get a visit from their child's 'home-room' teacher (we're expect- ing one next week) to establish rapport and discuss parents' worries, if any. We have, for instance, brought up the question of the racial and cultural differences between us and our neighbours, simply as something we are aware of, but have not found troublesome. At the end of the school year there is another meeting to discuss the children's progress. Five times a year per child, parents are expected (in Japan this is an expectation of iron) to attend demon- stration classes, standing at the back and following the lessons. Last Saturday, for instance, we both listened to a lesson in the mysterious subject dohtoku, 'morals and ethics', which before the war consisted of exhortations on hard work and unswerving obedience to the Emperor's (i.e. the bureaucracy's) com- mands. Malindi's teacher, Mori sensei (who has three children himself) instead produced a finger-bowl and explained that in some countries people used these uten- sils at table after, for example, eating asparagus, a vegetable little known in Japan. This led him to a disquisition on the variety of human folkways and the import- ance of recognising that none were in- herently superior or inferior, an admirably liberal message. Other teachers use their hour of dohtoku to catch up on other subjects. There is no exam or grading in dohtoku, although serious subjects like science and Japanese are tested at least fortnightly.

There is no corporal punishment in Japanese state schools. Children who offend by noisiness or inattention can be sent outside the classroom for five or ten minutes, ordered to perform zazen (zen meditation, supposedly on the vanity of earthly desires, while seated and staring straight ahead) for a like time, or in extreme cases sent to the teachers' room for a homily. Latecomers are sometimes shamed into 'volunteering' for unpopular jobs, like leading English conversation. Discipline is basically maintained by split- ting the class into five or six han, squads (not the same one that walks to school) and holding every child responsible for the behaviour of his or her han.

There is a squad leader, the hancho (another Buggins's turn job) whose duties include announcing at thd beginning of each period, 'Now we are going to study arithmetic', or whatever, and at the end thanking the teacher for the lesson and leading the class in a deep bow. The system carries into adult life and you owe the quality control of your Japanese television or camera, for instance, to the group vigilance in the factory of something like a children's han. The responsibility is seen as being, not to the boss, but to each other (`don't let the side down, chaps') and it is justified by the most Confucian of all arguments. It works.

Nothing that could be called religion is taught in Japanese schools, and certainly not the doctrine that Emperor Akihito and all the other Japanese are descended from the Sun Goddess. In fact we lately moni- tored a lesson of Alex's on the Yayoi people, ancestors of the Japanese, who inhabited our village some 12,000 years ago. His teacher did not explain in so many words where the Yayoi came from, but when we asked him later, Malindi inter- posed in the weary tone bright young ladies use to dim parents, 'from Korea, of course!' Our children help carry the mikoshi, the portable shrine at village Shinto festivals, which Christian Japanese parents normally forbid on the ground that Shinto is idolatrous, but these are a village, and not official occasions. Our children think Shinto great fun.

Japanese schools are often depicted as hells of Darwinian competition but this is certainly not true of the primary system. There is no streaming, classes are balanced with the bright and not-so-bright, and marks, communicated to parents, are not made public. The school sports are, in fact, designed to avoid one-to-one competition, partly to enable the handicapped children to participate on equal terms. Japanese combat sports like judo and kendo, which all seem to have originated in killing people, are not taught. Instead, team sports like baseball, soccer and relay racing (on foot and in the school swimming-pool) are played. Handicapped students are often in the winning teams.

The theme of co-operation closes the school day, when pupils and teachers

JAPANESE SPECIAL

combine to clean the school, sweeping the classrooms and corridors, dusting the blackboards and scrubbing out the toilets. These jobs are done in strict rotation, teachers working with their pupils and, on appropriate days, parents summoned to weed and rake the playground. Schools in Japan, China, Korea and Vietnam employ no school cleaners, one of the great divides of the educational world which tells us much that is favourable about the attitude towards education of the countries of the Confucian tradition.

Where, then, do stories about the Japanese 'examination hell', the mental breakdowns and child suicides come from? As the American educator John Dewey teaches us, education is not a preparation for life, but part of life itself. The mutual help, the reasonableness, the concern for the unlucky and less gifted is very much part of Japanese life, although it is a part that foreigners seldom see (although, if we approach with an open mind, we are welcome to share its benefits and obliga- tions). One result of patience with the less endowed has been to give Japan, overall, the best educated and most diligent labour force in the world, the basis of all Japanese successes.

The Confucian design has another side. The master taught that education should be as widespread as possible in order to find those, irrespective of class, most fitted to serve the state. Japan's productive, co-operative groups are directed by a bureaucratic hierarchy selected by ex- aminations, perhaps the ablest and certain- ly the most arrogant of their breed to be found anywhere. Japanese industry, com- nierce, the military are all run by the same kind of snooty hierarchs. Up to the age of about 15, the end of the ninth year of compulsory education, the Japanese gov- ernment schools are excellent. We would without hesitation recommend them to any parent, to those of less gifted children who will get at least as much respect and attention as the others, and to those with bright and imaginative children as well, because they are guaranteed a grounding in the hard subjects that just have to be learnt. Tough as the syllabus is, some 95 per cent of Japanese children complete it, an unmatched national asset.

But, at that age (end of junior and beginning of senior high school in Japanese terms) the funnel starts to narrow, the pressure goes on. Schools compete with schools, classmates with classmates for the htruted number of slots-for-life in the bureaucracy and business. Private, fee- Paying schools proliferate at this point to serve the rich, while the notorious juku (after-hours cram schools) force-feed the children of ambitious parents with, as they promise, the secrets of passing exams. This is the area of scandal, of bribed examiners, stolen papers and suicidal children. Not surprisingly, individuality and creativity wither in this jungle. The Japanese univer- sities, run on rigid hierarchical lines, don't do much to revive them, much to the alarm of concerned Japanese.

Our own children, for reasons of nationality and custom, have little prospect of ever being Japanese bureaucrats (although, in a fast changing world, you never know) and so we intend to send them to no juku, offer no bribes and hold them out of the Oriental rat-race as best we can. But, up to now, we have nothing but good to report of a system which has many, not always well-informed, critics. But then, none of us went to Japanese schools.

Previous page

Previous page