ARTS

Exhibitions 1

London's Pride: the History of the Capital's Gardens (Museum of London, till 12 August)

The glory of the gardens

Mary Keen

Going to look at gardens indoors is a paradox which is losing its power to sur- prise. I can't think why, because an exhibi- tion which tried to synthesise the inside outside would seem very odd. We have had birdsong at the V & A, wheelbarrows at Sotheby's, Miss Jekyll's boots at the gates of Lambeth Palace and tangerine trees at Christie's. Now in the heart of that con- crete tomb, where you feel you may never again see the light of day, synthetic garden- ing has arrived. No birds sing at the Barbican, where the Museum of London is staging its London's Pride exhibition of the history of the capital's gardens, but there is a smell of pot-pourri in the air. Silk flowers abound and when you get to around 1830, the background music changes from music- al box Vivaldi played over and over again to the sort of band that you might hear in the park. Standing on the threshold of the Victorian age you can hear both early and late music simultaneously. Around the section on Bedford Park there was running water overhead, but this may have been the Barbican plumbing, rather than more sound effects.

The organisers have taken the gift- wrapped, Lark Rise to Candlefordl Diary of an Edwardian Country Lady route. You know this because there is no proper catalogue, only a glossy book (Anaya, £25), to accompany the exhibition. This is a desperate omission. There are brilliant things to see but no catalogue. Can you believe it? The book contains essays by such scholars as Lord Harris of Tweed,

Todd Longstaffe Gowan and Dr Brent Elliot, but this is no substitute for a commentary on what is on show. The illustrations are rarely what you see in the exhibition and what plates there are are captioned at the back of the book. If the exhibits had been as disappointing as the Country Lady ambience I would not dwell on this lack. But as there are all sorts of things which have not been seen before and which may not be seen again without a huge effort from the spectator, it would (N.B. N.B. Museum of London) have been nice to take a catalogue home for future reference and past reminder.

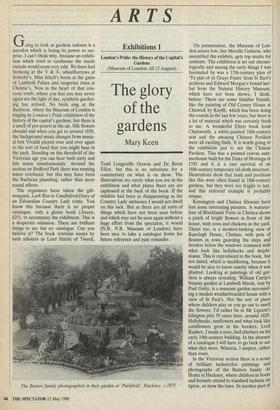

The Butters family photographed in their garden at `Parkfield', Hackney, c1875 On presentation, the Museum of Lon- don scores low, but Mireille Galinou, who assembled the exhibits, gets top marks for contents. The exhibition is set out chrono- logically and among the early things I was fascinated by was a 17th-century plan of `Ye plat of ye Graye Friars' from St Bart's archives and Edward Morgan's bound her- bal from the Natural History Museum, which have not been shown, I think, before. There are some familiar friends, like the painting of Old Corney House at Chiswick by Knyfft, which has been doing the rounds in the last few years, but there is a lot of material which was certainly fresh to me. A wonderful Ehret book from Chatsworth, a white-painted 18th-century seat and the amazing Chinese Pavilion were all exciting finds. It is worth going to the exhibition just to see the Chinese Pavilion. This was a painted canvas sum- merhouse built for the Duke of Montagu in 1745 and it is a rare survival of an 18th-century temporary oil-cloth structure. Illustrations show that tents and pavilions like this were often found in 18th-century gardens, but they were too fragile to last, and this restored example is probably unique.

Kensington and Chelsea libraries have lent some interesting pictures. A waterco- lour of Blacklands Farm in Chelsea shows a patch of bright flowers in front of the house, with cows and chickens in the yard. Theirs too, is a modern-looking view of Ranelagh House, Chelsea, with pots of flowers in rows guarding the steps and borders below the windows crammed with what look like hollyhocks and delphi- niums. This is reproduced in the book, but not dated, which is maddening, because it would be nice to know exactly when it was planted. Looking at paintings of old gar- dens is always revealing. William Curtis's botanic garden at Lambeth Marsh, lent by Paul Getty, is a museum garden surround- ing a modest weatherboarded house with a view of St Paul's. Not the sort of place where children play or you go out to smell the flowers; I'd rather be in Mr Lipcott's Islington plot 50 years later, around 1820. Hollyhocks, sunflowers and what look like cornflowers grew in his borders. Lord Radnor, I made a note, had climbers on his early 19th-century building. In the absence of a catalogue I will have to go back to see what they were. Wisteria, I suspect, rather than roses.

In the Victorian section there is a series of brilliant technicolor paintings and photographs of the Butters family At Home in Hackney, where children in boots and bonnets attend to standard fuchsias on tiptoe, or mow the lawn. In another part of the garden, little beds like jam tarts are dotted all over the grass and there is a spindly weeping willow. I wish I could remember more of these pictures. Of course they are not illustrated in the book and as they are privately owned, I doubt we will see them again.

There is a good 20th-century section. A David Jones view of suburban gardens lent by Portsmouth and a funny garden in Wimbledon with a tennis-ball fountain caught my eye. So did the allotments in St James's Square painted by Adrian Allin- son, with a theatre sign showing Blithe Spirit.

In the Garden Court is perhaps the most interesting part of the show. Here you really are out of doors and this has been designed as a living history of London nurseries from the Middle Ages to the Present day. A paved path takes you past a series of chronological beds containing nurserymen's wares, so that you can see what was available to gardeners at any given time. Virginia Nightingale was re- sponsible for assembling the plants, under the guidance of John Harvey, who is famous for his scholarly research into nurserymen's catalogues. She has so far failed to find Fairchild's Mule, a cross between a sweet william and a carnation, but she has collected a brilliant haul of old varieties and this part of the exhibition, which is permanent, should get better and better. But in accordance with museum Policy there is again no catalogue of this very academic exercise. There is a glossy booklet on London's nurserymen written by John Harvey, but there are no lists of the plants assembled. They are on a computer and in the ground, but please, London Museum, if we can't have a proper catalogue of the exhibition, and if you want to be taken seriously as a museum, can we have a record of this sequence of plants? A typed list will do.

Previous page

Previous page