Theatre

Troilus and Cressida (Stratford)

Troy boys

Christopher Edwards

The anti-heroic tenor of this Shakespeare work lends itself to our age. All traces of military idealism surrounding the Trojan War are either undercut or debunked. The Greeks are depicted as disorderly brutes and schemers. The Tro- jans — although more sympathetically portrayed — suffer from a self-destructive idealism. As for romantic love, it receives a distinctly disenchanted treatment. Ideals of love, war and beauty are examined with great intellectual rigour but Shakespeare appears to question their ultimate purpose. And, throughout, he notes the relentless march of time.

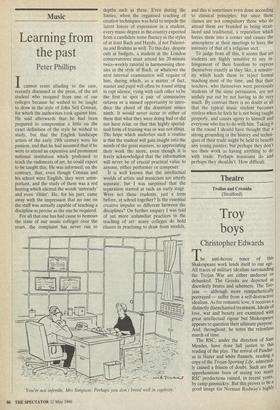

The RSC, under the direction of Sam Mendes, have done full justice to this reading of the play. The arrival of Pandar- us in blazer and white flannels, reading a copy of the Trojan Sporting Life, admitted- ly caused a frisson of doubt. Such are the apprehensions born of seeing too many RSC productions ruined, in recent years, by camp gimmickry. But this proves to be a good image for Norman Rodway's highlY watchable and repellent old bawd.

The production is designed in an eclectic style. Stiff collars, mediaeval breastplates, Greek helmets and Angle-poise lamps invest the action with a timeless air, without ever sinking to self-congratulatory cleverness. And the occasional laughs pro- voked by the props are genuinely satirical. When Agamemnon has to resort to holding up his desk card to prove his identity to a Trojan envoy, the visual gag follows per- fectly upon Ulysses's great speech on order. The war is being fought by commit- tee. Similarly the sound of the blues issuing tinnily from a transistor radio provides a suitably ironic prelude to a visit to the tent of the sulking Achilles.

In any case, self-consciousness and play- acting is rife, at least in the Greek camp. Ciaran Hinds's Achilles is portrayed as a vain, sinister creep. Dressed in black leath- er trousers, a black string vest, and wearing his hair slicked down, he postures and lowers like a moody playboy. Sylvester Morand's Agamemnon is a seedy tippler. Richard Riding's Ajax is very funny in- deed. He is hugely built, doltish and easily manipulated by Paul Jesson's subtle Ulys- ses.

The shabbiness of the Greeks is well expressed in their tatty appearance; seven years at the gates of Troy'have taken their toll on their wardrobe as well as on morale. By contrast, the Trojans dress immaculate- ly. David Troughton's Hector is a dominat- ing presence. Courteous and honourable, his simple-minded belief in fair play proves fatal. But there is seediness too underlying Trojan honour and chic. John Warnaby's epicurean Paris wheels on Sally Dexter's scarlet-robed pin-up of a Helen as if she were a steamy turn in a night-club floor show. So much for the Trojan cause.

The lovers after whom the work is named are excellently played. Ralph Fien- nes invests Troilus with a candour and dignity that are both winning and affecting. Having bedded Cressida, he grows in emotional stature up to and beyond the scene where he witnesses her switch affec- tions to a Greek captor. Amanda Root's Cressida eschews any feminist justifica- tions and is played, with conviction, as the traditional wanton.

The final word rests with Simon Russel Beale's brilliant Thersites, whose invective blasts and debases everything it touches. Dressed in a dirty mac, hunchbacked, red-nosed and with his head clamped inside a brown leather cap, he opens his scurrilous account by dropping a great gob of spit into Ajax's food. Everything else he serves up is, metaphorically, laced with the same venomous garnish. Fool and Chorus rolled into one deformed shape, this is a masterly performance of perfect comic timing and riveting penetration. This pro- duction of Troilus and Cressida is not only compelling and first-rate, it is worth suffer- ing the purgatory of a trip to Stratford the highest praise I can bestow.

Previous page

Previous page