HOW CLARKE WON (BUT ONLY SO FAR)

Michael Gove goes behind the scenes of the ex-Chancellor's leadership campaign and finds it impressive but flawed KENNETH CLARKE started the cam- paign for the Conservative leadership as the Establishment choice, Curzon in a crumpled suit. He was the candidate of Viscount Whitelaw, Douglas Hurd and Nicholas Soames. Lord Snooty backed the Bash Street Chancellor.

In contrast, William Hague ran as the voice of the grass-roots, the People's William. Asked who his heavyweight sup- porters were, his spin doctors would reply, `We have the country.' Mr Hague may yet live up to those hopes, but this weekend the starting positions are subtly reversed and Ken Clarke is the country candidate, William Hague the Court's.

The story of how Mr Clarke won the wider party but, appar- ently, lost the bigger prize is a tale of two campaigns. Mr Clarke's leadership campaign was far more tightly organised than the shadow Chancellor's demeanour might suggest. But the minds of many in the par- liamentary party had already been made up in the general election campaign.

Mr Clarke's stubbornness in refusing to rule out a single currency prevented Mr Major from giving his European policy in the election the clarity it needed. Mr Clarke's decision, after the Tories' defeat, to reveal that he would not have taken Britain into EMU anyway was not seen in Central Office as a Piece of winning candour. Although he told the Tory party conference in 1993 that 'any enemy of John Major is an enemy of mine', several of Mr Major's friends concluded that that must, out of a crowded field, make Ken Clarke his own worst enemy.

Whatever Mr Clarke expected the conse- quences of his actions to be, his campaign team drew a certain bitter comfort from the general election result. As one of them explained, 'The one good thing you could say about the defeat is that it exonerated Ken. The scale of it meant that you couldn't say we lost just because we didn't have the right policy on Europe.' The elec- tion could become a matter of character, rather than policy. That, the team thought, would play into their hands. 'All the other candidates had character flaws, the only criticism of Ken was on policy, and that was shown not to matter.'

Having decided that their theme would differentiate them sharply from the rest of the field, the Clarke supporters settled on tactics that would do the same. While other candidates courted the media, calling regu- lar press conferences, designing flashy backdrops and writing 'thoughtful' mani- festos as though there were a world out there to woo, the Clarke team, like Labour at the last election, targeted the only voters who would count. Rather than trying to carry the country, as in a general election, they concentrated on converting MPs.

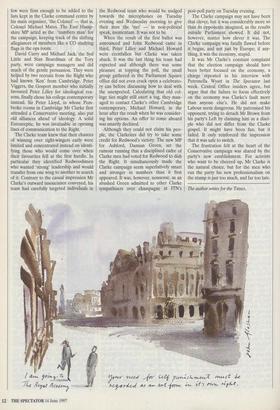

Mr Clarke was telephoned relentlessly in the opening days of the campaign by sever- al journalists, anxious for him to make his pitch in their paper. He politely declined them all, explaining insouciantly that he was 'moving house'. Like John Major's need to convalesce after his wisdom tooth operation in 1990, which neatly removed him from the scene of the crime when Mar- garet Thatcher was assassinated, the incon- venience proved very convenient. As Mr Clarke explained to an aide, 'This is an election with 164 voters — it's them I've got to talk to.' A Tory leadership election is always a series of seductions and the lesson of the seducers' cautionary tale, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, is simple — never commit to paper that which is better spoken.

Mr Clarke set to speaking, and speaking, and speaking. One of his supporters gave vent during the campaign to gentle exas- peration at the amount of time lavished on winning over unlikely waverers. A parade of potential supporters trooped into his Commons room in an accommoda- tion block overlooking Parliament Square. Mr Clarke did not troop round the country himself. All the other contenders con- ducted regional tours to meet the grass-roots. Ken sent them a video. It may have seemed like the ulti- mate insult from the couch potato candidate but it worked. The more the grass-roots saw of the oth- ers, the less enthused they became. They preferred professionalism. By declin- ing to stoop, Ken con- quered.

It was the impression of growing support in the constituencies for Mr Clarke that led Stephen Dorrell to endorse the shadow Chancellor. Mr Dor- rell had chosen to stand because he believed no other candidate could unite the Conservative party in the country. His con- cern about a Clarke candidacy was the reaction among activists. When Mr Clarke won them, he also vanquished Mr Dorrell's doubts.

Mr Dorrell's was, however, the only sur- prising endorsement Mr Clarke secured from the parliamentary party's depleted ranks. Many members were charmed by the shadow Chancellor's pitch as he puffed away in his exile eyrie opposite the Trea- sury he once graced. As they left, however, few were firm enough to be added to the lists kept in the Clarke command centre by his main organiser, 'the Colonel' — that is, Colonel Michael Mates. The East Hamp- shire MP acted as the 'numbers man' for the campaign, keeping track of the shifting allegiances of members like a CO studying flags in the ops room.

David Curry and Michael Jack, the Syd Little and Stan Boardman of the Tory party, were campaign managers and did much of the gentle persuasion. They were helped by two recruits from the Right who had known 'Ken' from Cambridge. Peter Viggers, the Gosport member who initially favoured Peter Lilley for ideological rea- sons, finally chose his college contemporary instead. Sir Peter Lloyd, in whose Pem- broke rooms in Cambridge Mr Clarke first attended a Conservative meeting, also put old alliances ahead of ideology. A solid Eurosceptic, he was invaluable in opening lines of communication to the Right.

The Clarke team knew that their chances of winning over right-wingers early were limited and concentrated instead on identi- fying those who would come over when their favourites fell at the first hurdle. In particular they identified Redwoodsmen who wanted 'strong' leadership and would transfer from one wing to another in search of it. Contrary to the casual impression Mr Clarke's outward insouciance conveyed, his team had carefully targeted individuals in the Redwood team who would be nudged towards the microphones on Tuesday evening and Wednesday morning to give their man the `mo' — in non-political speak, momentum. It was not to be.

When the result of the first ballot was announced and John Redwood came in third, Peter Lilley and Michael Howard were crestfallen but Clarke was taken aback. It was the last thing his team had expected and although there was some pleasure at topping the poll, the small group gathered in the Parliament Square office did not even crack open a celebrato- ry can before discussing how to deal with the unexpected. Calculating that old col- lege ties might still exert a tug, they man- aged to contact Clarke's other Cambridge contemporary, Michael Howard, in the hour after the result when he was consider- ing his options. An offer to come aboard was smartly declined.

Although they could not claim his peo- ple, the Clarkeites did try to take some credit for Redwood's victory. The new MP for Ashford, Damian Green, set the rumour running that a disciplined cadre of Clarke men had voted for Redwood to dish the Right. It simultaneously made the Clarke campaign seem superlatively smart and stronger in numbers than it first appeared. It was, however, nonsense, as an abashed Green admitted to other Clarke sympathisers over champagne at ITN's post-poll party on Tuesday evening.

The Clarke campaign may not have been that clever, but it was considerably more so than its opponents imagined, as the results outside Parliament showed. It did not, however, matter how clever it was. The Clarke campaign was fatally flawed before it began, and not just by Europe; if any- thing, it was the economy, stupid.

It was Mr Clarke's constant complaint that the election campaign should have been better focused on the economy, a charge repeated in his interview with Petronella Wyatt in The Spectator last week. Central Office insiders agree, but argue that the failure to focus effectively on the economy was Clarke's fault more than anyone else's. He did not make Labour seem dangerous. He patronised his opponent, trying to detach Mr Brown from his party's Left by claiming him as a disci- ple who did not differ from the Clarke gospel. It might have been fun, but it failed. It only reinforced the impression that it was safe to switch.

The frustration felt at the heart of the Conservative campaign was shared by the party's new establishment. For activists who want to be cheered up, Mr Clarke is the natural choice, but for the men who run the party his new professionalism on the stump is just too much, and far too late.

The author writes for the Times.

Previous page

Previous page