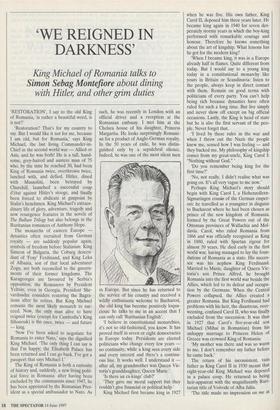

WE REIGNED IN DARKNESS'

King Michael of Romania talks to

Simon Sebag Montefiore about dining

with Hitler, and other grim duties

`RESTORATION', I say to the old King of Romania, 'is rather a beautiful word, is it not?'

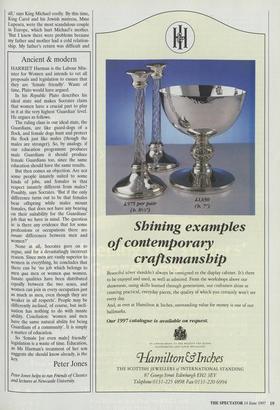

`Restoration? That's for my country to say. But I would like it not for me, because I am old, but for Romania,' says King Michael, the last living Commander-in- Chief in the second world war — Allied or Axis, and he was both! He is a tall, hand- some, grey-haired and austere man of 75 who, by the time he reached 30, had been King of Romania twice, overthrown twice, lunched with, and defied, Hitler, dined with Mussolini, been betrayed by Churchill, launched a successful coup d'etat against Hitler's stooge, and finally been forced to abdicate at gunpoint by Stalin's henchmen. King Michael's extraor- dinary life of glory, adventure, tragedy and now resurgence features in the novels of The Balkan Trilogy but also belongs in the Ruritanian romances of Anthony Hope.

The monarchs of eastern Europe dynasties often recruited from German royalty — are suddenly popular again, symbols of freedom before Stalinism: King Simeon of Bulgaria, the Coburg descen- dant of `Foxy' Ferdinand, and King Leka of Albania, son of that local adventurer Zogu, are both reconciled to the govern- ments of their former kingdoms. The Karageorges are favoured by Serbia's opposition; the Romanovs by President Yeltsin; even in Georgia, President She- vardnadze considers restoring the Bagra- tions after he retires. But King Michael remains the most likely monarch to suc- ceed. Now, the only man alive to have reigned twice (except for Cambodia's King Sihanouk) is the once, twice — and future — king.

`Now I've been asked to negotiate for Romania to enter Nato,' says the dignified King Michael. 'The only thing I can say is that I'm happy; the Elisabeth Palace has been returned and I can go back. I've got a passport that says Michael I.'

The King of Romania is both a curiosity of history and, suddenly, a new living polit- ical force in Romania: after having been excluded by the communists since 1947, he has been appointed by the Romanian Pres- ident as a special ambassador to Nato. As such, he was recently in London with an official driver and a reception at the Romanian embassy. I met him at the Chelsea house of his daughter, Princess Margarita. He looks surprisingly Romani- an for a product of Anglo-German royalty. In the 50 years of exile, he was distin- guished only by a sepulchral silence. Indeed, he was one of the most silent men in Europe. But since he has returned to the service of his country and received a wildly enthusiastic welcome to Bucharest, the old king has become positively loqua- cious: he talks to me in an accent that I can only call `Ruritanian English'.

`I believe in constitutional monarchies, it's not so old-fashioned, you know. It has proved itself in seven or eight democracies in Europe today. Presidents are elected politicians who change every few years no continuity, while a king sees every side and every interest and there's a continu- ous line. It works well. I understand it after all, my grandmother was Queen Vic- toria's granddaughter, Queen Marie.'

`Is there an ex-kings' club?'

`They gave me moral support but they couldn't give financial or political help.' King Michael first became king in 1927 when he was five. His own father, King Carol II, deposed him three years later. He became king again in 1940 for seven des- perately stormy years in which the boy-king performed with remarkable courage and honour. Therefore he knows something about the art of kingship. What lessons has he got for the modern king?

`When I became king, it was in a Europe already half in flames. Quite different from today. But I would say to a young king today in a constitutional monarchy like yours in Britain or Scandinavia: listen to the people, always keep in direct contact with them. Remain on good terms with politicians of every party. You can't help being rich because dynasties have often ruled for such a long time. But live simply and never show off except on big official occasions. Lastly, the King is head of state but he is also the first servant of the peo- ple. Never forget that.

`I lived by these rules in the war and when I threw out the Nazis the people knew me, sensed how I was feeling — and they backed me. My philosophy of kingship comes from my great-uncle, King Carol I: "Nothing without God." ' `Do you remember being king for the first time?'

`No, not really, I didn't realise what was going on. It's all very vague to me now.'

Perhaps King Michael's story should begin with King Carol I, a Hohenzollern- Sigmaringen cousin of the German emper- ors: he travelled as a youngster in disguise to Bucharest where he had been chosen as prince of the new kingdom of Romania, formed by the Great Powers out of the Ottoman provinces of Wallachia and Mol- davia. Carol, who ruled Romania from 1866 and was officially recognised as King in 1880, ruled with Spartan rigour for almost 50 years. He died early in the first world war, having managed to lay the foun- dations of Romania as a state. His succes- sor was his nephew King Ferdinand. Married to Marie, daughter of Queen Vic- toria's son Prince Alfred, he brought Romania into the first world war beside the Allies, which led to its defeat and occupa- tion by the Germans. When the Central Powers collapsed, the Allies created a greater Romania. But King Ferdinand had problems with his heir, the disastrous, over- weening, confused Carol II, who was finally excluded from -the succession. It was thus in 1927 that Carol's five-year-old son Michael (Mihai in Romanian) from his unhappy marriage to Princess Helen of Greece was crowned King of Romania: `My mother was there and was so warm to me. I don't remember my father before he came back.'

The return of his inconsistent, vain father as King Carol II in 1930 meant that eight-year-old King Michael was deposed in a palace coup. He returned to being heir-apparent with the magnificently Ruri- tarian title of Voivode of Alba Julia.

`The title made no impression on me at all,' says King Michael coolly. By this time, King Carol and his Jewish mistress, Mme Lupescu, were the most scandalous couple in Europe, which hurt Michael's mother. `But I knew there were problems because my father and mother had a cold relation- ship. My father's return was difficult and unhappy for my mother.'

`Did you realise the dangerous way King Carol was conducting politics?'

`Slowly it grew on me that I was living in a most unsavoury environment at home. I wasn't frightened. My father liked his posi- tion and didn't want to lose it. We never talked heart to heart. Maybe it was the influence of this . . . person around him.'

Even 70 years later, King Michael can- not bear to utter the name of that infa- mous scarlet woman, Lupescu.

`But I had to meet her. I didn't hate her. She was simply a very vulgar person. I had lots of friends and flirtations but not lots of girlfriends. I was watched carefully, con- stantly. Bucharest was decadent. My early life was luxurious. I enjoyed cars, collected a few.'

In his ten years' reign, the blundering but dictatorial King Carol unsuccessfully tried to steer Romania to peace, between the circling forces of Stalin's ravenous Russia and Hitler's voracious Germany, while simultaneously trying to suppress Roma- nia's own fascists, the Iron Guard, with characteristically ineffective ruthlessness.

`Romania was between Hitler and Stalin, the hammer and anvil, as we say in Roma- nia. It is that way today, which is why we want to protect our new democracy by joining Nato. . . . '

After Germany and Russia divided Europe in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Stalin forced King Carol to cede his province Bessarabia. As the country itself fell more and more under the sway of Hitler, who needed its oil, the broken King Carol abdicated in 1940. The Voivode of Alba Julia, now a teenager, was king again: `I was taken by surprise. When the crisis came, it came in the midst of the night. . . . We all knew the fascist Iron Guard was horrible, so I expected something. At eight in the morning, I was ordered by General Antonescu to dress and take the oath. In the beginning, we didn't know what sort of man Antonescu was.'

General, later Marshal, Antonescu was the new dictator (`the Conductator' he called himself in the tradition of 'der Fiihref and Duce'), who made Roma- nia a close ally of Hitler, granted him use of Romanian oilfields and lent him Roma- nian armies to fight against Russia 150,000 Romanians died at Stalingrad alone.

`Antonescu and I had very strange rela- tions. Antonescu loved his country but went about it the wrong way. He treated me as a child, excluded me. I hated having a dictator. By the end of 1942, I was con- vinced something had to be done.'

`Did you visit the Russian front?'

`Antonescu made me. I reviewed our troops in Crimea.'

`You met Hitler?'

`Yes, I lunched with him twice. The first time was in 1938 with my father at the Berchtesgaden in Bavaria and then as king myself in Berlin in 1941. I was on my way with my mother to see the king of Italy in Florence when Antonescu said if I was seeing the king of Italy and Mussolini, I had to see Hitler first.'

`What was it like for a young king to lunch with the Riltrer?'

`Hitler was stiff and unfriendly and you couldn't get near him as a person, even lunching next to him. He'd suddenly get onto a subject. His eyes went glassy and he started declaiming. I tried to speak, but you couldn't interrupt. Goering was much friendlier. But we didn't like them at all. Their style, their behaviour went against our grain. But some of their officers knew how to behave: there were still a few aristo- cratic officers around Hitler then. They were more correct. While Hitler spoke, I just stuttered. An ADC came in to whisper some victory in his ear but Hitler didn't stop lecturing. The last thing I remember him saying was, "I guarantee America will never enter the war against us." I didn't believe him. There was something not right with him.'

Did you prefer Mussolini?'

`Mussolini was voluble, gesticulating, friendly: a contrast with Hitler like day and night.'

After 1942, the young king entered the cloak-and-dagger world of spies and shad- ows: `We intensified our secret efforts with the Allies in Cairo and Turkey. Bucharest crawled with spies. Loyal patriots helped us. I let Antonescu know that I was not happy but he said, "Keep quiet, you're still a child." The Germans had good planning and engineering but their way of thinking was utterly foreign to us. The only thing we had in common was that we were anti- Stalin.'

Meanwhile, the Holocaust was mas- sacring the Jews of Europe: `I was in contact with the Chief Rabbi, who came to see my mother. We prevent- ed much of what they wanted to do and that is why my mother is a Righteous Gen- tile, honoured in Israel.'

The King secretly became leader of the opposition to Marshal Antonescu: `I planned the coup in conjunction with the opposition parties including Commu- nists and Socialists. It was exciting to make the plans to stop the slaughter — the cul- mination of secret work from 1942 to 44. On 23 August 1944, I summoned Antones- cu and he arrived . . . late as usual. I said he must make an armistice at once. He flatly refused to do so without Hitler's permission so I nodded at the head of my Military Household and I told Antonescu, "If you don't want to do it, let somebody else." Antonescu became furious: "I'm not leaving the country in the hands of a child." So I spoke the agreed sign: "There is nothing else for me to do." At which three NCOs and a captain burst in and led him up to the King's safe where my father used to keep his stamp collection. I locked him in there. Then we formed a new gov- ernment.'

Romania changed sides and joined the Allies, but it was too late. Churchill was about to sign over 90 per cent of influence in Romania to Stalin at Yalta: Stalin's envoy, the reptilian Vyshinsky, the infa- mously vicious prosecutor-general in Stal- in's showtrials in the Thirties, arrived soon afterwards. Vyshinsky taunted King Michael with Churchill's decision: 'I am Yalta,' he liked to say ominously.

`I was rather taken aback that Churchill had done this at Yalta — the reaction was that it was a betrayal. Possibly Stalin tricked him.'

The communists were closing in, infil- trating the government, building up their own secret police, isolating the democratic politicians and the young King. There was little hope of escaping Stalin's descending Iron Curtain. 'Vyshinsky was a real brute — never really angry but pretending to be as a façade, slamming the doors.'

In 1947, King Michael went to attend the marriage of his cousin Princess Eliza- beth of England to Prince Philip. The com- munists presumed he would never return.

`But I had to, it was my duty. In fact, at the wedding Churchill told me so — he advised, "Return!" But the wedding was very nice. You do things like that better in England than anywhere else in the world.'

`Was it difficult watching Elizabeth II reign so long while you were in exile?'

`Yes, it's been a struggle morally and financially,' says King Michael, an old monarch who still manages to achieve the dignity of royalty in his threadbare suit. His father King Carol, who died in the Fifties, had escaped with the dynastic riches, most of which he squandered. King Michael escaped with nothing.

When the final coup against him came, the young King was newly engaged.

`They said they wished to see me about "a family matter". So I thought it was about my fianc6e. They came to see me, the pre- mier and the Communist leader Dej. They produced a bit of paper. It was the abdica- tion — that's what they meant by "a family matter". The grammar was not good. They could hardly even write; so I would not sign. But they said, "Your guards have been arrested; the telephone is cut; and there is artillery pointed at this very office." I looked out of the window. Everything they said was true: there was a howitzer pointed at me. I tried to delay, suggesting we ask the people. "No time to ask the people," they said. "There'll be disturbances and we'll shoot the whole lot and it would be your fault." I was disgusted at how low these people were. And I signed.'

`Did you enjoy being king?'

`It was not a normal time. It was a daily battle in a time of war. It was a terrible burden. There was no pleasure in being king in those circumstances. But my coup of 23 August gave me great satisfaction. And today we love our country too much not to do what we can.'

`You wish to reign again after all those troubles?'

`I would not want to be king for me but for what I could do for my countrymen helping to let democracy take hold. A con- stitutional monarchy might be a fine way to keep Romania free and democratic. Nato would give us security to be part of Europe.'

`Was it hard in exile?'

`Being a king brought up in a certain job, it was a terrible handicap, in the dark, feel- ing your way.'

`Do you still have nightmares about the day you lost your kingdom?' `We reigned in a time of darkness over Europe, not like today when all seems light. But, you see, you're never free of the past.'

Simon Sebag Montefiore writes for the Sunday Times. His novel, My Affair with Stalin will be published in September by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Previous page

Previous page