Profile

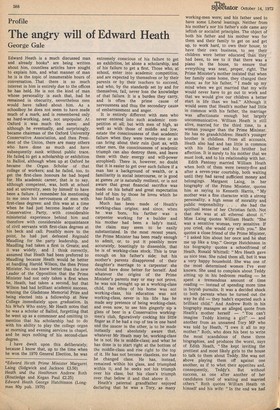

The angry will of Edward Heath

George Gale

Edward Heath is a much discussed man and already books* are being written about him, countless articles have sought to explain him, and what manner of man he is is the topic of innumerable hours of conversation. That there is so much interest in him is entirely due to the offices he has held. He is not the kind of man whose personality is such that, had he remained in obscurity, nevertheless men would have talked about him. As a schoolboy he does not seem to have made much of a mark, and is remembered only as hard-working, neat, not unpopular. At Oxford it was much the same; and although he eventually, and surprisingly, became chairman of the Oxford University Conservative Association, and then President of the Union, there are many others who have done as much and have subsequently sunk without public trace. He failed to get a scholarship or exhibition to Balliol, although when up at Oxford he became the Organ Scholar of that college of workers; and he failed, too, to get the first-class honours he had hoped for. His academic career, that is to say, although competent, was, both at school and at university, seen by himself to have been a failure. I remember his mentioning to me once his nervousness of men with first-class degrees: and this was at a time when he had just become leader of the Conservative Party, with considerable ministerial experience behind him and therefore with considerable acquaintance of civil servants with first-class degrees at his beck and call. Possibly more to the point, he had just defeated Reginald Maudling for the party leadership, and Maudling had taken a first in Greats; and it was widely, and I think correctly, assumed that Heath had been preferred to Maudling because Heath would be better at handling Harold Wilson, the then Prime Minister. No one knew better than the new Leader of the Opposition that the Prime Minister had not only taken a first when he, Heath, had taken a second, but that Wilson had had brilliant academic success, winning the Gladstone Memorial Prize and being elected into a fellowship at New College immediately upon graduation. In his Who's Who entry, Mr Heath notes that he was a scholar of Balliol, forgetting that he went up as a commoner and omitting to mention that his scholarship had to do with his ability to play the college organ at morning and evening services in chapel, and he says nothing of his second-class degree.

I have dwelt upon this deliberately; because I know that, up to the time when he won the 1970 General Election, he was extremely conscious of his failure to get an exhibition, let alone a scholarship, and of his failure to get a first. Those who, at school, enter into academic competition, and are expected by themselves or by their parents or by their teachers to succeed, and who, by the standards set by and for themselves, fail, never lose the knowledge of that failure. It is a burden they carry, and is often the prime cause of nervousness and thus the secondary cause of embarrassment and anger.

It is entirely different with men who never entered into such academic competition at all; but with men of high, 'as well as with those of middle and low, estate the consciousness of that academic failure when they were twenty-one or so can bring about their ruin (just as, with other men, the consciousness of academic triumph can also destroy them, and leave them with their energy and will-power atrophied). There is, however, no doubt that it is easier to get over such failure if a man has a background of wealth, or a familiarity in social intercourse, or is good at games ,or is naturally resilient, or is not aware that great financial sacrifice was made on his behalf and great expectation held of him by those he loves which he has failed to fulfil.

Much has been made of Heath's working-class origins; and since, when he was born, his farther was a carpenter working for a builder and his mother had been a lady's maid, the claim may seem to be easily substantiated. In the most recent years, the Prime Minister has been ready enough to admit, or, to put it possibly more accurately, boastingly to dissemble, that he is of working-class stock. This is true enough on his father's side; but his mother's parents disapproved of their daughter's marriage to a carpenter: she should have done better for herself. And whatever the origins of the Prime Minister's parents may or may not prove, he was not brought up as a working-class child, the ethos of his home was not working-class, his education was not working-class, never in his life has he made any pretence of being working-class, and even now, to see him gingerly sip a glass of beer in a Conservative workingmen's club, figuratively cocking his little finger as if he had a cup of tea in one hand and the saucer in the other, is to be made instantly and absolutely aware that, whatever Mr Heath may be, working-class he is not. He is middle-class; and what he has done is to start right at the bottom of the middle-class and rise right to the top of it. He has not become classless, nor has he changed class. He has, instead, remained within his Class, and triumphed within it; and he seeks not his triumph over his class, but his class's triumph over that below it and that above it.

Heath's paternal grandfather enjoyed declaring that he was a Tory, as many working-men were; and his father used to have some Liberal leanings. Neither from his mother's nor his father's side came any leftish or socialist principles. The object of both his father and his mother was for them and their family to get on and get up, to work hard, to own their house, to have their own business, to see their children were better educated than they had been, to see to it that there was a piano in the house, to ensure that everything was neat, proper, right. The Prime Minister's mother insisted that when her family came home, they changed their shoes; as for his father, "I made up my mind when we got married that my wife would never have to go out to work and that we would give our children a better start in life than we had." Although it would seem that Heath's mother had little in common with his father, the marriage was affectionate enough but largely uncommunicative. William Heath is still alive, married for the third time, to a woman younger than the Prime Minister. He has no grandchildren: Heath's younger brother is childless. From all accounts, Heath also had and has little in common with his father and his brother but affection. It is surely to his mother that we must look, and to his relationship with her.

Edith Pantony married William Heath when both of them were twenty-five and after a seven-year courtship, both waiting until they had saved sufficient money and belongings. Margaret Laing, in her biography of the Prime Minister, quotes him as saying to Kenneth Harris, "My mother was a fine character with a strong personality, a high sense of morality and public responsibility . . . she had the spiritual sense of her Christian faith. Not that she was at all ethereal about it." Miss Laing quotes William Heath: "She was a sensitive woman, very sensitive. If you cried, she would cry with you." She quotes a close friend of the Prime Minister, "I asked him about her once and he shut me up like a trap." George Hutchinson in his biography quotes a schoolfriend of Heath, Ronald Whittell: "Mrs Heath gave us nice teas. She ruled them all, but it was a very happy household. She was one of the most determined women I've ever known. She used to complain about Teddy sitting up in his bedroom reading — he spent a tremendous amount of time reading — instead of spending more time in boyish pursuits. It was a decided shock to both parents when he turned out the way he did — they hadn't expected such a brilliant child." And Andrew Roth in his biography manages an alleged quote from Heath's mother herself — "You can't imagine Teddy kissing a girl" — and another from an unnamed Tory MP who was told by Heath, "I owe it all to my mother." Roth, who does his best to write the most scandalous of these three biographies, and produces the worst, says of Edith Heath, "She kept inviting the prettiest and most likely girls to the house to talk to them about Teddy. She was not above playing them off against one another, as if to whet their appetites and consequently, Teddy's. But without success, as one after another of her candidates tired of waiting and married others." Roth quotes William Heath on himself and his wife: "In the end we had nothing to talk about except the children."

It is an unsatisfactory picture which we get from such quotations, and Edith Heath, nde Pantony, remains shadowy. Mr Bird, Teddy's teacher at Chatham House school, says of Mrs Heath: "She was constantly stopping when we met in the street to know how her Teddy was getting on. She was a charming woman, but always looked very tired. I thought she was probably overworked. They used to take in summer visitors at home." When Heath was asked at Oxford why he did not smoke he replied, "I am not going to waste my mother's money." William Heath's wedding boast, that he would not allow his wife to go out to work, did not prevent him from allowing his wife to work throughout each summer season taking in lodgers in a squashed house; and it is reasonable to suppose that Teddy Heath, uncertainly at first, but with growing confidence, carving out a career for himself at Oxford, must have been aware that the piano in his rooms, his books, the white tie and tails demanded by his union ambitions, depended upon his mother's taking in summer visitors in their semidetached three-bedroomed villa called ' Helmdon ' in King Edward Avenue, Broadstairs.

Margaret Laing quotes an Oxford friend: "If we were going out swimming he wouldn't strip off in front of me — but he wouldn't obviously not, either. He's fairly ' pi ' — I think that may be his mother's influence. She was very pure." Miss Laing continues: He did not appear to be very much at ease with the women undergraduates, sharing the general tendency of the young men of the time, other than those from sophisticated circles, to hold them in rather low, if nervous esteem. "He's always been rather tight with women," comments an acquaintance of very different demeanour. "Some people think it might be a reaction against his father." (It is true that his father's naturally flirtatious manner still earns him a degree of envy from octogenarian contemporaries.) Some of his friends cannot remember seeing him with a girl. Madron Seligman clearly remembers going up to London with him and two girls to hear the Ninth Symphony; they stopped at Henley to picnic on the way. The very clarity of the recollections suggests that this was something of an event. His friendship with Kay (Raven) in Broadstairs continued (and of course the vacations, most of which he spent at home) lasted for about half the year. When he was told about the love lives of other young men he was shocked if they indulged in fornication — both his religious and home upbringing had left him in no dougt that this was wrong. But it was quite impossible to go through four years at Oxford leading a sheltered life, untouched by the exploits, the fears and desires, the arguments and sometimes the inaities of his contemporaries.

One wonders about parts of the long summer vacations spent at home, when his mother was busy taking in her summer lodgers. One wonders, too, about his fourth year at Oxford, the young Heath then doing nothing much it seemed about getting a job, but going on a debating tour of the United States, and then waiting to be called up. In the summer of 1939 he went with Madron Seligman to Germany and Poland; but he was not called up until the end of July, 1940. The war must have been a relief: the postponement of a very necessary decision —What to do? He had already had more than a taste of politics, fighting for the Master of Balliol, Lindsay, against Quinton Hogg in the Oxford byelection, visiting Spain and being confirmed in his anti-fascism, attending a Nuremberg rally: but, What to do? or, How to get there? By now Heath was twenty-four. Oxford had not much opened, or changed his mind; but it must have closed him up. His mother's sacrifices would eventually have to be rewarded, her purity acknowledged, her ambition for him fulfilled, and her love requited. He went through his war; and his war, again, was a further education and a further preparation. Afterwards, demobilised, again, What to do? How to get there? How to justify and how to repay? The war, no more than Oxford, had neither loosened him nor opened him up. He had a year in the Civil Service; and over a year at the Church Times; but politics was the answer to his questions and only through politics could the angry will be satisfied.

It is easy enough to understand Heath's success once he had been adopted and had then been returned as member for Bexley: he had the application, but above all he possessed the most powerful ambition of his contemporaries — with the possible exceptions of Enoch Powell and of lain Macleod. To understand the Prime Minister it is necessary to understand the nature of his ambition and its angry, ruthless quality; and it is necessary also to understand how it is that he has done without a sexual life and also without, after the death of his mother when he was thirty-four, any deep and lasting love. I do not think such understanding is possible without grasping that his ambition and his solitariness have to do with his mother: his ambition must be satisfied to repay her; his solitariness flows from her irreplaceability. I suspect that his anger comes from the knowledge that she was a servant and that also she worked — slaved? — for him. I suspect, too, that he could only advance himself by denying, in his style of living, those, and she in particular, who made the advance possible and for whom it was made. That his ambition — rather, his will — is angry, I do not doubt; nor do I doubt that his solitariness is fortified by a barrier made of the tissues of scars left by innumerable social scratches, bruises, abrasions, cuts and deeper wounds suffered during his early life.

It is difficult to use the word 'nice 'in a way which is not somewhat pejorative or superior; but it nevertheless needs to be said that Ted Heath is a nice man. He is strong and he is tough but he is also kind and thoughtful, and I believe him to be as good and as honest a man as it is possible for an angry and ambitious politician to be. I also believe him to be as civilised and cultured as it is possible for a solitary and uncommunicative man to be, who has lived, and been, alone throughout his adult life. I both admire and like him, and although I think it is a great misfortune that the cause which has been the principal practical beneficiary of his angry will has been the cause of Britain in Europe, I have to acknowledge that, if he succeeds in his European policy, it will be easily the most formidable historical achievement of any British prime minister since Clement Attlee constructed the Welfare State and organised the independence of India between 1945 and 1947. It is unnecessary to approve of the Attlee achievement to recognise its magnitude and its potency. But Attlee's was a corporate achievement: it was not an expression of his will, although doubtless he desired what was done. The Heathian achievement, if it be consummated, will be the consequence and expression of his will, far more than that of his Cabinet or of his Party. And Attlee in his time enjoyed the support of the country, whereas Heath's European policy runs counter to it.

At times I have suspected that such is the scale of his ambition, the anger of his will, that to be Prime Minister is not enough; to be the Prime Minister who takes Britain into Europe will not be enough; but that to be the undisputed leader of a Europe who is consequently able to treat as primus inter pares with the President of the United States and the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Chairman in China will alone be enough for the son of the servant from Broadstairs. Whether this be so or not, whether he succeeds in his policies at home and abroad or is destroyed by them or by other circumstance, there is a nobility about the angry will of Ted Heath, just as there is a nobility in the solitary man who, alone in his rooms, turns on the hi-fl as loud as possible so that he is steeped in and almost drowned by the sublimating symphony, while drinking whisky steadily but with control.

Previous page

Previous page