Exhibitions

Theatre of Reason/Theatre of Desire: Art of Alexandre Benois and Leon Bakst (Villa Favorita, Lugano, Switzerland, till 1 November)

Exotic turns

Robin Simon

The scent of cypresses is heavy in the air. It is already hot at 11 in the morning. The light bounces off the waters of the lake, the MV Paradiso splashes past: the local water-borne bus service doing the rounds. The steep cone of Monte San Sal- vatore is still sharply outlined. It is perfect for a stroll to that most perfectly situated of all art galleries, the Villa Favorita, home of the Thyssen-Bomemisza Foundation in Lugano, and so I am on my way to the opening of the latest exhibition.

Such events are a recent innovation, for, until the vast bulk of the fabled Thyssen collection was relocated in the Vilaher- mosa in Madrid in 1992, this was the prin- cipal home of the permanent display. The Favorita has therefore been reinvented: the main gallery has been redesigned, and the selection of masterpieces from the perma- nent collections it now contains (including a definitive life-size Lucian Freud portrait of the Baron) is complemented by chang- ing temporary exhibitions.

At first, the Favorita was looked after by the Baron's rather wonderful daughter Francesca, she of a famous no-knickers photograph, and now more decorously the Archduchess von Habsburg, who still takes a close interest in the place (she is expect- ed this afternoon). It now has its own director/curator, Maria de Peverelli, who has organised the new exhibition, which is devoted to the work of that famous Ballets Russes duo, Leon Bakst and Alexandre Benois.

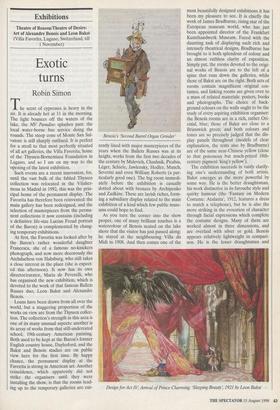

Loans have been drawn from all over the world, but a staggering proportion of the works on view are from the Thyssen collec- tion. The collection's strength in this area is one of its many unusual aspects: another is its array of works from that still-underrated school, 19th-century American painting. Both used to be kept at the Baron's former English country house, Daylesford, and the Bakst and Benois studies are on public view here for the first time. By happy chance, the permanent display at the Favorita is strong in American art. Another coincidence, which apparently did not strike the organisers until they were installing the show, is that the rooms lead- ing up to the temporary galleries are cur- Benois's 'Second Barrel Organ Grinder' rently lined with major masterpieces of the years when the Ballets Russes was at its height, works from the first two decades of the century by Malevich, Chashnik, Picabia, Leger, Schiele, Jawlensky, Hodler, Munch, Severini and even William Roberts (a par- ticularly good one). The big room immedi- ately before the exhibition is casually dotted about with bronzes by Archipenko and Zadkine. These are lavish riches, form- ing a subsidiary display related to the main exhibition of a kind which few public muse- ums could hope to find.

As you turn the corner into the show proper, one of many brilliant touches is a watercolour of Benois seated on the lake shore that the visitor has just passed along: he stayed at the neighbouring Villa du Midi in 1908. And then comes one of the most beautifully designed exhibitions it has been my pleasure to see. It is chiefly the work of James Bradbume, rising star of the European museum world, who has just been appointed director of the Frankfurt Kunsthandwerk Museum. Faced with the daunting task of displaying such rich and intensely theatrical designs, Bradbume has brought to it both splendour of colour and an almost ruthless clarity of exposition. Simply put, the rooms devoted to the origi- nal works of Benois are to the left of a spine that runs down the galleries, while those of Bakst are on the right. Both sets of rooms contain magnificent original cos- tumes, and linking rooms are given over to a mass of related materials: posters, books and photographs. The choice of back- ground colours on the walls ought to be the study of every aspiring exhibition organiser: the Benois rooms are in a rich, rather Ori- ental, blue; those of Bakst are close to a Brunswick green; and both colours and tones are so precisely judged that the dis- play panels throughout (models of clear explanation, the texts also by Bradbume) are of the same near-Chinese yellow (close to that poisonous but much-prized 18th- century pigment ling's yellow').

The exhibition succeeds in vastly clarify- ing one's understanding of both artists. Bakst emerges as the more powerful by some way. He is the better draughtsman, his work distinctive in its farouche style and quirky humour (the 'Fantasy on Modern Costume: Atalanta', 1912, features a dress to match a telephone), but he is also the more striking in the evocation of character through facial expressions which complete the costume designs. Many of them are worked almost in three dimensions, and are overlaid with silver or gold. Benois appears relatively lightweight in compari- son. He is the lesser draughtsman and Design for Act IV, Arrival of Prince Charming 'Sleeping Beauty, 1921 by Leon Bakst always nearer in his figures to caricature than characterisation. Yet there is a sensu- ous richness to some of his work and some remarkable flights of fancy, especially in the latter part of his much longer career: he remained prolific throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and the exhibition includes many examples of his theatre designs for Paris, New York and Milan.

Benois died at the age of 90 in 1960, and had improved with age. By 1924 Bakst was dead at 58, but left an incomparable legacy of designs that almost define for posterity the Ballets Russes at its most exotic. Even his name is suitably exotic, although we know how many balletic noms de dance hide humble origins: it is only a little deflating to discover that Bakst was a sur- name adapted from the more mundane Baxter.

Previous page

Previous page