Ringling's big top Baroque

Susan Moore on one of the great unsung art collections in America Ca d'Zan? Even the most seasoned traveller looks puzzled. For this Venetian Gothic edifice — its name means 'House of John' in Venetian dialect — rises up not from the Grand Canal or some obscure island campo but from the waterfront of Sarasota Bay on the west coast of Florida. The John who built it in 1924 was perhaps the most famous of all circus kings, John Ringling, but his most extraordinary and enduring legacy is the far grander Raiianate villa-cum-palace that he raised in its grounds. This is the unlikely home to one of the great unsung art collections of America.

There is more than a whiff of the surreal about Ringling's pink palazzo. Roofline, courtyard and lush terraces are punctuated by casts of Antique and Renaissance sculpture, swaying palms and banyan trees. Outside is a sub-tropical seaside paradise; inside, arguably the greatest collection of Italian Baroque painting out of Italy — and much else besides. The Ringlings acquired their considerable treasures in just six years, a great deal of it bought during thei i annual trips to Europe to audition new circus acts. The incongruities are delicious: one moment lion tamers, the next Lot and his Daughters; the bearded lady meets Samson and Delilah. As it turns out, the whole Ringling experience is hardly less fantastical.

The question that itches to be answered is why a circus-man, albeit a phenomenally successful one (in his heyday Ringling's estimated worth was $200 million), the son of an immigrant German harness-maker, was compelled to do what no Frick. Morgan or other American plutocrat had done and go off in serious pursuit of deeply unfashionable masterpieces of Italian Baroque art.

It is too simplistic just to stand in jaw-dropping amazement at the door of the museum's immense first two galleries and see the showman's taste for spectacle — and imagine his delight in the glorious theatricality and luscious paint of the monumental tapestry cartoons by Rubens. Even so, there are few museum experiences to rival it. As the elderly gentleman who walked in beside me put it, `Aw, where's the church?'

Unlike comparable institutions, The John a design for his museum in 1925, he had not bought a single museum-quality work of art. Mr John, as he was known, was the front man of the five Ringling Brothers, the businessman who also masterminded the logistics of moving and feeding a travelling troupe of 1,200 when the tigers alone required 22 lbs of meat a day. He remained devoted to the circus — he and Mable rarely missed a season on the road — but as movie houses began to mushroom in every small town he shrewdly diversified into railroads, oil and real estate.

In 1921 he joined the Florida land-boom, acquiring valuable property on the Sarasota waterfront and keys to develop a fashionable metro-resort like Palm Beach on Florida's Atlantic coast, predicting a $100 million return on his 510 million investment. The jewel in the crown was to be a Ritz-Carlton Hotel, lavishly ornamented with architectural antiques and sculpture dispatched by the ton from Europe. These fountains, statues and doorcases were to find another use when the market slump halted the hotel venture. In 1925 the manager of the New York Ritz-Carlton had introduced the Ringlings to the German art dealer Julius Baler and Ringling's vague notion of building a showcase museum and art school as a cultural asset for his developing resort turned into a reality. Buying began in earnest for the museum that the childless Ringlings now saw as their memorial.

In spring 1926 John Ringling purchased three complete Gilded Age rooms designed by Richard Morris Hunt for the Astor mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York. A month later he acquired from the Duke of Westminster — against the advice of his dealer — Rubens's great 'Triumph of the Eucharist' tapestry cartoons that had hung at Grosvenor House in London. Commissioned by the Infanta Isabella, governor of the Spanish Netherlands, around 1625, these designs are a tour-de-force of Counter Reformation propaganda. While the 11 tapestries were presented to the Convent of the Poor Clares in Madrid, Isabella kept the cartoons. Philip IV later sent them to Spain where they remained until Napoleonic troops liberated some of them. Four were subsequently acquired by the Iron Duke in 1818. These canvases (another was acquired by the museum in 1980) set the tone and established a benchmark of quality for the whole collection.

Ringling was fortunate to be buying at a time when the aristocracy — on both sides of the Atlantic — was obliged to sell. From the legendary Ho[ford sales at Christie's in London in 1927-28, for instance, Ringling hoovered up no less than 33 pictures — among them the full-length portrait of Philip IV by Velasquez, now the museum's most valuable trophy. In 1928, he bought the Gavet Collection of more than 300 Late Mediaeval and Early Renaissance works of art — sculpture, maiolica and metalwork — from the Vanderbilts' house on Rhode Island. Museums were deaccessioning too. That year he also bought some 2,300 pieces from the world-class Cesnola Collection of predominantly Cypriot antiquities sold at auction by the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Between 1925 and 1931 he amassed some 600 Old Masters.

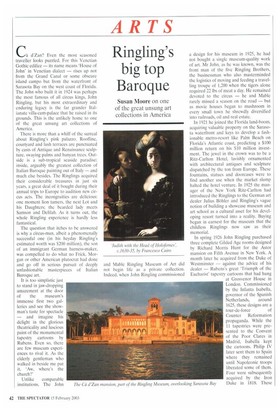

Ringling was opportunistic but he was also discriminating. A comprehensive library of art books and auction catalogues, along with annotations and correspondence, suggest that he looked carefully at prospective purchases. Given the advances in scholarship, it is only to be expected that numerous attributions have not stood the test of time. What is striking about the Ringling's galleries, however, is that there are minor masterpieces even among the demoted canvases. Dominating the Renaissance galleries, for instance, is the extraordinary scowling patriarch standing with his family in an imposing Venetian portrait now thought not to be by Veronese but by his pupil Giovanni Antonio Fasolo. The arresting, candid gaze of the Caravaggesque 'Judith with the Head of Holofernes' by the Milanese Francesco Cairo is another gem.

In a rare public statement about his museum. Ringling said that he wished to develop a collection as nearly universal as opportunities and purse would allow. As it turned out, its particular strength is north European and Italian Baroque painting. While Duveen — who, incidentally sold Ringling the largest known Gainsborough portrait, of Lieutenant General Philip Honywood — was a big promoter of the likes of Rembrandt and HaIs, the Italian Baroque had few admirers. Ringling bought both — he paid his highest price of 8100,000 for Hals's spirited portrait of Pieter Jacobsz Olycan (the Rubens cycle cost him the same). No doubt it appealed to him that the Italian artists were cheap by comparison, and big and showy. Nonetheless, well out of the mainstream of essentially puritan American taste, these pictures reflect a bold and independent spirit.

The Ringling has always been something of a well-kept secret — even its recent inspired refurbishment and reinstallation excited little attention outside the local press. Like our own V&A it suffers an identity crisis — everyone presumes it is a museum of the circus. Thanks to the flamboyant Chick Austin, the museum's first director, the Ringling now has that too — as well as an 18th-century theatre shipped in from Asolo. The appeal of this ever evolving, fantastical place is that it bears the stamp of its founder's personality without being set in aspic. The Ringling Museum may not be The Greatest Show on Earth, but it is one of them

Previous page

Previous page