INSIDE THE CASTLE

Dominic Lawson questions

the Czechoslovak President about capitalism and Germany

Prague WHEN Mrs Thatcher flies into what is now called the Czech and Slovak Federal Re- public, for her meeting on Monday with President Vaclav Havel, the following things will happen to her: her pilot will remind her that it is forbidden to take photographs over Czech air space, and that when she lands she must exchange foreign currency at the state bank at the airport.

There she will find she is forced to buy Czech crowns at an invented rate of 30 to the pound, barely half the amount she would receive on any street corner in Prague. She will notice that any small change handed to her will still bear the imprint of the hammer and sickle. She will no longer be rendering unto that particular Caesar, but I think we would all recognise this as a socialist transaction. In fact probably none of these things will be forced on Mrs Thatcher — prime ministers are special cases — but they will be on the bevy of English journalists accompanying her, unless policies have changed since last week when I made the same journey, to interview President Havel.

The political table-talk in Prague is that while the finance minister, Vaclav Klaus, an unreconstructed supporter of Milton Friedman, is aching to introduce market economics to the country, even to intro- duce private sector restaurants, President Havel is obstructing him. Havel himself seemed almost affronted when I put this — hardly controversial — point to him.

'That is of course a mistake. It is a nonsense. Some people think it because that's the way it appears in our newspap- ers, but they do not reflect the real truth. Mr Klaus and I agree that the reform must be speedy and profound, although it is not really a reform but in fact a substitution of the existing system by a different one.'

Perhaps the argument therefore is at a different level, namely, what shall be the nature of the new system? When I asked Mr Havel if he was prepared to have capitalism in Czechoslovakia, he replied, with some asperity, 'I have never said that we should build capitalism in our country. We want to build a functioning economic system, on which prospering economies and trade have been based for millennia, that is, long before capitalism arrived on the scene.'

I'm not sure what Mrs Thatcher will make of that when she attempts to per- suade the President of her ideas of a Pan-European Common Market, in which the newly liberated Eastern European countries would be full members of the capitalist club. Havel, as he put it to me, is 'a friend of various co-operative, collective forms of ownership, but at the same time I can see that purely private ownership has a legitimate right to exist parallel to them'.

Switch the meaning of that sentence on its head, and you arrive at the view of the British Prime Minister.

The last time the two leaders met was at a dinner thrown in Havel's honour at 10 Downing Street. A fellow guest said later that he had never seen two people sitting next to each other with less in common.

Havel grinned impishl■ when I recounted this remark to him, and then in his charac- teristic rumbling monotone attempted a serious response.

'Whether sitting at the dinner table next to Mrs Thatcher we are symbolising two different worlds' — here Havel broke off to stub out yet another cigarette — 'that is not up to me to judge. But it's always a useful experience for everybody — the confrontation with someone who may think in a different way.'

Is President Havel, the unwitting hero of the Right in the West, in fact a socialist? In 1968, when he was among a group dedi- cated to reviving the extinct Social Demo- cratic party, Havel said in an interview, 'I was always in favour of socialism in the sense of nationalisation of the major means of production.' When I reminded Havel of this, he retorted, 'I might have said some- thing like that, but my opinions have developed as I am learning to know the world. If I in the past accentuated the collective form of ownership more than I accentuate it today, perhaps it is because today I am some 20 years older.' So, come clean now, Vaclav, are you still a man of the Left or not?

'I have been refusing all my life to be identified as a leftist or a rightist. For many years I have been suspected by some of being a leftist, and by others of being a rightist, and at the same time both groups claimed me, and I just had to laugh.'

I was just about to remind Havel of Timothy Garton Ash's first law of politics in Eastern Europe post-1989: the man who says he is neither a leftist nor a rightist is a leftist. But then finally, after an agonising- ly long drag at a cigarette held between thumb and forefinger, he answered the question: 'Nevertheless, I should probably say one thing: God created me in such a way that my heart is on the left side of my chest, and I will not deny my affiliation with the . . let's say . . . liberal-minded international intellectual community, which is called by some left-wing.'

This conflation of God and the Left is in fact evident in the bookshelf in Havel's peculiarly modest and angular little office in the vast building overlooking Prague, known to all simply as 'the Castle'. Behind Havel and the clouds of smoke emanating from him I could make out, almost in a row, two copies of the Bible, a biography of Mother Teresa, and a plaque with the name of Olof Palme engraved on it. So, having established, at least to my own satisfaction, Havel's political credentials, I also had to ask, 'Are you a Christian?'

'I would not call myself a particularly good Christian, or even a practising Catho- lic, but at the same time I admit openly that my overall view of the world and its mysteries has been affected by my Christ- ian upbringing and environment.'

It is tempting to see an element of the Christian doctrine in the reluctance of the new administration to launch into prosecu- tion and sentencing of those who brutalised and oppressed the likes of . . . Vaclav Havel, during the period of communist rule. Whether or not there is an element of forgiveness in this, it is a matter of intense debate among those who once suffered as dissidents; one of them, now a member of parliament, told me, 'The Velvet Revolu- tion has been velvet mostly for the beasts and freaks who used to run this country.' I repeated interrogatively exactly these words to Havel.

'First, we didn't invent the term Velvet Revolution. It was invented by Western journalists, and then it began to be used here as well. In my opinion it is not a very fortunate expression. As to your question, the situation is a complicated one. The revolutionary process is still going on while at the same time we are building the legal state. That means, as a matter of principle, that we want to avoid all acts of revenge, and to open the way for justice. The implementation of that justice is, I agree, not often as perfect as it should be. But if, on the other hand, we let the revolution take justice into its own hands we would join the fate of tevolutions devouring their own children, responding to violence with violence.'

At this point the man sitting next to President Havel on the presidential sofa, sipping the presidential bitter lemon, nod- ded vigorously in agreement. This was none other than Prince von Schwarzen- berg, Havel's Chancellor. And the Prince ought to know about such things. After all, he is a direct descendent of the Prince von Schwarzenberg who for his Habsburg mas- ters put down the 1848 Revolution in Austria with such unsentimental efficiency.

Despite his name, von Schwarzenberg is in fact a Czech citizen, so I was able without embarrassment to ask Havel about . . . the Germans. Any visitor to Prague will seem to hear German spoken almost as much as the language of the natives, and bright new Mercedes and BMWs litter the streets of the city, dwarfing the Skodas which are all the locals can aspire to. As President, Havel himself is driven in a cavalcade of BMWs, at least one of them a gift from the German President, Richard von Weizsacker. I recalled to Havel the remark he made in his inaugural speech as President, in January: 'Our state should never again be an appendage or a poor relation of anyone else.' Does that include Germany?

'I personally don't share the fear that Czechoslovakia could become a satellite and appendix of the uniting huge and rich Germany. We do not have to be afraid of a democratic neighbour. We can always reach an agreement with a democracy.

There does exist in this part of the world a kind of historical genetically coded fear concerning the Germans, but it seems to me that this tradition should be patiently opposed. We should fight the subconscious fear, rooted in our tradition, of Germans as such.'

I don't suppose anyone in the room could altogether forget that we were sitting in what might have been the private office of Heydrich, when that Nazi was the 'protector' of Bohemia.

But why, I asked Havel, should the genetic trait only be a characteristic of those uneasy about German power? Why could there not be some undesirable gene- tic characteristics in the Germans them- selves, as listed by Mrs Thatcher's adviser, Mr Charles Powell?

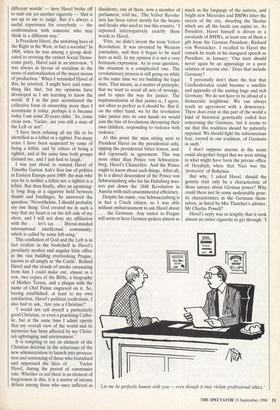

Havel's reply was so lengthy that it took almost an entire cigarette to get through: 'I 'Let me be perfectly honest with you — even though it may violate professional ethics.' should perhaps correct myself, and say that I use the word genetic in inverted commas. Of course it is not the result of genetics but of social and historical tradition. It is an expression of archetypes transferred from one generation to another. For example we can observe now the fears expressed by Poland about its western border, which seems to us excessive and unneces- sary. . . . I can't at the same time rule out the possibility that in some fraction of the German population there exists some sort of expansionist archetype, but it does not seem to me to be the policy of the new Germany or the will of the German public. I consider it a marginal phenomenon.' So, no need to worry about undue German influence on the Czech economy. But I couldn't help noticing the inscription on the lighter with which Havel was fiddling throughout our interview. It was the logo of BMW. 'What's that then?' I asked Havel. He gave a wry little grin, and scuttled across his office to his desk, threw the lighter into a drawer, rummaged around for a few seconds, found what he was looking for, shuffled back, sat down, and banged another lighter down on the table between us. This one had the unmis- takable twelve-starred emblem of the European Community. Then we all laughed, not too nervously.

Previous page

Previous page