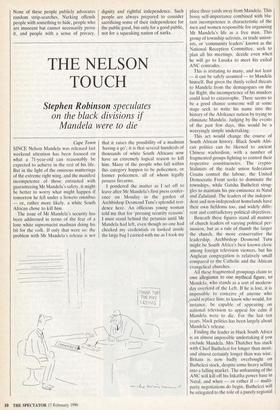

THE NELSON TOUCH

Stephen Robinson speculates

on the black divisions if Mandela were to die

Cape Town SINCE Nelson Mandela was released last weekend attention has been focused on what a 71-year-old can reasonably be expected to achieve in the rest of his life. But in the light of the ominous mutterings of the extreme right wing, and the manifest incompetence of those entrusted with guaranteeing Mr Mandela's safety, it might be better to worry what might happen if tomorrow he fell under a Soweto omnibus — or, rather more likely, a white South African chose to kill him.

The issue of Mr Mandela's security has been addressed in terms of the fear of a lone white supremacist madman doing his bit for the volk. If only that were so: the problem with Mr Mandela's release is not

that it raises the possibility of a madman 'having a go'; it is that several hundreds of thousands of white South Africans now have an extremely logical reason to kill him. Many of the people who fall within this category happen to be policemen, or former policemen, all of whom legally possess firearms.

I pondered the matter as I set off to leave after Mr Mandela's first press confer- ence on Monday in the garden of Archbishop Desmond Tutu's splendid resi- dence here. An officious young woman told me that for 'pressing security reasons' I must stand behind the petunias until Mr Mandela had left, even though no one had checked my credentials or looked inside the large bag I carried with me as I took my

place three yards away from Mandela. This bossy self-importance combined with bla- tant incompetence is characteristic of the men and women responsible for organising Mr Mandela's life as a free man. This group of township activists, or trade union- ists, or 'community leaders' known as the National Reception Committee, seek to plan all his meetings, decide even when he will go to Lusaka to meet his exiled ANC comrades.

This is irritating to many, and not least — it can be safely assumed — to Mandela himself. But given the thinly veiled threats to Mandela from the demagogues on the far Right, the incompetence of his minders could lead to catastrophe. There seems to be a good chance someone will at some stage seek to write his name into the history of the Afrikaner nation by trying to eliminate Mandela. Judging by the events of the past few days, this would be a worryingly simple undertaking.

This act would change the course of South African history. Black South Afri- can politics can be likened to ancient Chinese warlordism, with a number of fragmented groups fighting to control their respective constituencies. The crypto- Stalinists of the trade union federation Cosatu control the labour, the United Democratic Front seeks to dominate the townships, while Gatsha Buthelezi strug- gles to maintain his pre-eminence in Natal and Zululand. The leaders of the indepen- dent and non-independent homelands have their own fiefdoms too, and widely diffe- rent and contradictory political objectives.

Beneath these figures stand all manner of church leaders of varying political per- suasion, but as a rule of thumb the larger the church, the more conservative the leadership. Archbishop Desmond Tutu might be South Africa's best known cleric among foreign television viewers, but his Anglican congregation is relatively small compared to the Catholic and the African evangelical churches.

All these fragmented groupings claim to owe allegiance to one mythical figure, to. Mandela, who stands as a sort of modern- day overlord of the Left. If he is lost, it is impossible to conceive iof anyone who

• could replace him; to know who would, for instance, be capable of appearing on national television to appeal for calm if Mandela were to die. For the last ten ,years. black politics has been largely about Mandela's release.

Finding the leader in black South Africa is an almost impossible undertaking if you exclude Mandela. Mrs Thatcher has stuck with Chief Buthelezi for longer than most, and almost certainly longer than was wise. Britain is now badly overbought on Buthelezi stock, despite some heavy selling into a falling market. The unbanning of the ANC will kill off his Inkatha power base in Natal, and when — or rather if — multi- party negotiations do begin. Buthelezi will be relegated to the role of a purely regional

leader representing rural Zulus, bolstered only by his personal associations with Mandela.

On the day of his release, Mandela said he was not a prophet, but a humble servant of the people, and a loyal, disciplined member of the ANC. The problem with his laudable modesty is that he is far larger and more important than the organisation to which he pledges humble obedience. Man- dela sits at the top, but there is little organisational structure between his pedes- tal and the people.

To see Mandela in action is a joy for anyone who has to cover anti-apartheid rallies or press conferences. He is not simply graceful, but he actually answers questions, addresses issues. He is a true politician in the sense that he knows what concerns ordinary people. His address after his Soweto homecoming was a mas- terstroke. He told the children to go back to school, denounced the behaviour of thugs who masquerade as activists, and deplored Soweto's 'appalling crime rate. These are matters which most directly affect the everyday lives of the 120,000 people crammed into the soccer stadium. No one else within broad anti-apartheid opposition could have dared to stray from ritual condemnations Of the regime and police brutality at such an important event.

Mandela has said he has acted as a mediator between the ANC and the gov- ernment, and suggested he would continue to do so if the ANC approved. But his really important role still probably lies in mediating between the warlords on his own side of the fence. He is the only person who has any chance of succeeding in pulling the black opposition together to negotiate with the most astute. Nationalist leader South Africa has ever produced. This is what makes Mandela's welfare of more than passing interest to hundreds of thousands of conservative whites.

Stephen Robinson is the Daily Tele- graph's Johannesburg Correspondent.

Previous page

Previous page