NEW LABOUR: WHO LOATHES WHO

Mr Brown and Mr Mandelson of course. But quite a few of the others too. It's nothing political,

Michael Gove explains, just personal NEW LABOUR may have abjured class conflict and abandoned the politics of envy but, as generations of socialist reformers have found, you cannot repeal human nature. Held in check until the election by the prospect of victory, but ready to emerge when the Daimlers are distributed, are sulphurous class prejudices and tradi- tional workplace jealousies. The primary victims of these resentments will not, how- ever, be hereditary peers or the chairmen of privatised utilities, but other members of the Labour Party.

The Conservatives, self-pro- claimed party of the nation, may be relied upon, from Belfast to Brussels, to get their betrayal in first, but Labour, the party of community, can rival Saddam Hussein's family in its capacity for fratricide.

This simple chardonnay-sipping/bitter- quaffing division is useful shorthand, but it masks the really interesting divisions. The old Left is a declining force, it is the dispo- sition of alliances, friendships and resent- ments within the broad Blairite tent that count, rather than any dreary head-count of the Left's Campaign Groupies. The con- tests that matter will be fought within the dominant grouping with personal feeling the casus belli and policy a weapon, not a motivation.

Nowhere will that be more obvious than in reactions to Gordon Brown. The shadow Chancellor, a university rector, Parliamentary candidate and published author while Blair was just an Ugly Rumour, possesses the most impressive mind in the party. As the example of Denis Healey proves, however, intellect is no substitute for charm in politics.

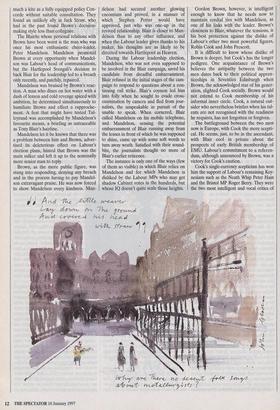

One Blairite sympathetic to Brown believes, 'It isn't just that Gordon doesn't suffer fools gladly, he doesn't suffer anyone gladly.' Brown's brusqueness mattered little while he was heir-apparent to John Smith, but when Smith died he found he was Antony, not Octavian.

Mr Blair's overtaking of Brown to assume the leadership inevitably affected a friendship once fraternal, still close, but now tinged with the bitterness of the passed-over. There are similarities with the relationship between Tony Crosland and Roy Jenkins a generation before. Crosland, like Brown, was the intellectual pathfinder of Labour revisionists, his brilliance occlud- ed by aloofness. Jenkins, like Blair, was considered the junior partner until events propelled him into more senior Cabinet office and saw him become the leader of the party's rising right-wingers. Although they continued to share an analysis, they no longer enjoyed the same intimacy.

Blair still relies on Brown, more than anyone in the shadow Cabinet, to provide modernising momentum. Brown still relies on Blair to protect him from internal crit- ics, but there were signs, earlier in this Par- liament, that — as an insurance policy Brown was protecting his own power base.

Brown's hand was detected behind the success of Tom Clarke, the Monklands West MP, in the 1995 shadow Cabinet elec- tions. Blair's hope of seeing fresh blood in the shadow Cabinet was frustrated by the election of Clarke, a colourless machine politician.

Many MPs thought Clarke incapable of victory on the basis of his own talents. One parliamentary colleague believes he was `over-promoted as a councillor' and, from his Bobby Charlton coiffure to his genuine interest in the disabled, he is hardly Mr Blair's vision of New Labour. Blair supporters who saw Brown and Clarke in cabal before the poll and heard of Brown's lieutenants canvassing for Clarke were incensed by his success. The Fife MP Henry McCleish, once one of Brown's staunchest supporters, tackled the shadow Chancellor head on in the Commons. McCleish, a for- mer professional footballer, got the better of the exchange and left Brown in no doubt that there was only room for one moral leader of Labour and it wasn't his fellow-countryman.

Support for Clarke was not the least of Brown's sins in the eyes of baby Blairites. His championing of the former campaigns director Joy Johnson in her battles with Peter Mandelson and the support his mar- shal, the Newcastle Whip Nick Brown, gave to Margaret Beckett during the leadership elections are both cited as evidence of his indulgence towards admirers who are not as loyal to the leadership as they should be.

Several senior Blairites have their own reasons for a certain coolness towards Brown. Mo Mowlam, the shadow Northern Ireland Secretary, once his underling in the trade and industry team, became disillu- sioned and suspicious of his commitment to Kinnock before 1992. Chris Smith and David Blunkett were bruised by the man- ner in which Brown chose to reveal his plans to reform child benefit, flying not so much a kite as a fully equipped policy Con- corde without suitable consultation. They found an unlikely ally in Jack Straw, who had in the past found Brown's decision- making style less than collegiate.

The Blairite whose personal relations with Brown have been worst is the man who was once his most enthusiastic cheer-leader, Peter Mandelson. Mandelson promoted Brown at every opportunity when Mandel- son was Labour's head of communications, but the Hartlepool Svengali's decision to back Blair for the leadership led to a breach only recently, and patchily, repaired.

Mandelson was bruised by Brown's reac- tion. A man who dines on hot water with a dash of lemon and cold revenge spiced with ambition, he determined simultaneously to humiliate Brown and effect a rapproche- ment. A feat that might have tested Tal- leyrand was accomplished by Mandelson's favourite means, a briefing as untraceable as Tony Blair's hairline.

Mandelson let it be known that there was a problem between him and Brown, adver- tised its deleterious effect on Labour's election plans, hinted that Brown was the main sulker and left it up to the nominally more senior man to reply.

Brown, as the more public figure, was stung into responding, denying any breach and in the process having to pay Mandel- son extravagant praise. He was now forced to show Mandelson every kindness. Man- delson had secured another glowing encomium and proved, in a manner of which Stephen Potter would have approved, just who was one-up in the revived relationship. Blair is closer to Man- delson than to any other influence, and when the Labour leader gives thanks to his maker, his thoughts are as likely to be directed towards Hartlepool as Heaven.

During the Labour leadership election, Mandelson, who was not even supposed to be involved in the Blair campaign, saved his candidate from dreadful embarrassment. Blair refused in the initial stages of the cam- paign to respond to questions about a con- tinuing rail strike. Blair's coyness led him into folly when he sought to evade cross- examination by camera and fled from jour- nalists, the unspeakable in pursuit of the unable to speak. When cornered, Blair called Mandelson on his mobile telephone, and Mandelson, sensing the potential embarrassment of Blair running away from the lenses in front of which he was supposed to shine, came up with some soft words to turn away wrath. Satisfied with their sound- bite, the journalists thought no more of Blair's earlier reticence.

The instance is only one of the ways (few of them so visible) in which Blair relies on Mandelson and for which Mandelson is disliked by the Labour MPs who may get shadow Cabinet votes in the hundreds, but whose IQ doesn't quite scale those heights. Gordon Brown, however, is intelligent enough to know that he needs now to maintain cordial ties with Mandelson, as one of his links with the leader. Brown's closeness to Blair, whatever the tensions, is his best protection against the dislike of Labour's other two most powerful figures, Robin Cook and John Prescott.

It is difficult to know whose dislike of Brown is deeper, but Cook's has the longer pedigree. One acquaintance of Brown's believes the antipathy between the two men dates back to their political appren- ticeships in Seventies Edinburgh when Brown, the acknowledged star of his gener- ation, slighted Cook socially. Brown would not extend to Cook membership of his informal inner circle. Cook, a natural out- sider who nevertheless bristles when his tal- ents are not recognised with the readiness he requires, has not forgotten or forgiven.

The battleground between the two men now is Europe, with Cook the more scepti- cal. He seems, just, to be in the ascendant, with Blair cool in private about the prospects of early British membership of EMU. Labour's commitment to a referen- dum, although announced by Brown, was a victory for Cook's caution.

Cook's single-currency scepticism has won him the support of Labour's remaining Key- nesians such as the Neath Whip Peter Hain and the Bristol MP Roger Berry. They were the two most intelligent and vocal critics of Brown's attachment to the ERM early in this Parliament. They used the authority of the Tribune Group to snipe at his willingness to manage the currency with the directors of central banks rather than the unemployed of Glasgow Central in mind. Brown's support- ers believe Cook took an altogether unseem- ly pleasure in the shadow Chancellor's discomfiture.

Cook is not the only shadow Cabinet member to employ the Cold War tactic of fighting proxy wars. John Prescott has encouraged his satellites to take on Brown's in constituency battles. Swindon North was the dirtiest fight. Brown's candi- date, the television executive Michael Wills, beat Prescott's man, the Rover shop steward Jim D'Avila, in the initial ballot, only to have D'Avila accuse him of ballot- stuffing. The fastidious and cerebral Wills, who could no more rig a constituency bal- lot than the Cutty Sark, was wholly inno- cent but only won through after appeals to the party's National Executive.

Brown, however, lost the most recent battle in Doncaster where his nominee, ironically a candidate from Prescott's own RMT union, was beaten by the deputy leader's former assistant, Rosie Winterton.

Winterton's triumph is also a victory for the sisterhood, adding to the impressive Amazon phalanx expected in the next Labour intake. But, in true Marxist terms, considerations of gender are still subordi- nate to those of class within New Labour.

In vulgar terms, there is a proletarian and provincial faction, the 'Nora Batties', and a more metropolitan and middle-class caucus, the 'Patsies and Edinas'. Nora Batties include Janet Anderson, the shadow women's minister; Helen Liddell, a Scottish frontbencher, and ballot-box-and-honking novelist; the Ulster-born Kate Hoey and Mo Mowlam. The Absolutely Fabulous tendency in Labour has Harriet Harman at its head and includes the shadow health minister Tessa Jowell and Patricia Hewitt, the former Kinnock aide and management consultant who is fighting Leicester West. All of the above are indistinguishably Blairite in ideol- ogy but separated by a cultural chasm.

Labour's leading Patsies, Harriet Harman and Tessa Jowell, live in South London's decaffeinated zone where, according to one back-bench cynic, they think social security worries are what Mary Killen deals with. In contrast, Ms Mowlam and Kate Hoey move in circles where the only Chelsea fashions which count are Ruud Gullit's plans for the back four.

The deepest tension between New Labour women is, like the battle between Bianca and Tiffany, a feud between two recently arrived East-Enders. The Dagen- ham MP, the former union official Judith Church, entertains a cordial dislike of the Barking member, Margaret Hodge, former leader of Islington council and wife of the wealthy solicitor, Henry Hodge. One asso- ciate of the earthy Ms Church puts the mutual antipathy down to the allegedly uppity manner of Mrs Hodge, 'like Raine Spencer without the common touch' according to another. Mrs Hodge, however, is dear to her leader, not just as an Isling- ton crony but as the Mata Had who turned Alan Howarth traitor to the Tories.

The supremacy of character and the death of ideology as the defining division between Labour's factions mark, more certainly than the rewriting of Clause Four or the reform of union links, the death of Bennery. The Chesterfield Leveller fought a long battle to make policies, not personalities, the matter of Labour's arguments. Now the party of progress is closer, in its clustering around patrons and power-mongers, to the Whigs under Fox than Labour under Foot.

That lesson has been learnt by the bat- tery of 'local heroes', an army of old coun- cillors turned New Labour candidates identified by the Public Policy Unit, a lob- bying firm with impeccable Labour links. Typical in background but outstanding in terms of talent is Graham Stringer, an old Bennite, who as leader of Manchester Council for 12 years learnt the importance of adaptability, but now recognises that preferment in the Commons is in the hands of the court not the country. His attach- ment to Blair won him the nomination for Manchester Blackley and should see him rise quickly in government.

Another lesser-known figure likely to enjoy patronage is the Coventry millionaire Geoffrey Robinson. Having put his house in Italy and his house journal, the New Statesman, at the leader's disposal, much as an 18th-century politician might have deployed hospitality and hired pens to win favour, he should secure an economic job. He is a director of Jaguar and Blairites hope he might play a role similar to Harold Lever's in the Wilson government, provid- ing business ballast.

But one of the clearest signs of Whiggery rests in the Labour leader's own choice of courtiers. In the 18th century the Whigs were the party of the rising merchant class, the Tories the landed interest. Blair's assid- uous wooing of businessmen has brought him cash, and credibility.

Where Kinnock, intellectually and socially less secure, basked in the reflected fame of luvvie limelight, Blair prefers to associate with the world of Fortune. Rather than sur- round himself with Mortimers, Folletts, Pin- ters and other salon socialists as Kinnock did, Blair has chosen to cultivate commerce. He has shown himself more at ease with people such as his economic adviser, the City economist Derek Scott, the late Matthew Harding, the recently ennobled businessman Swraj Paul and the broadcasting millionaire Barry Cox, as well as entertainment entrepreneur Michael Levy — those who are FT pink rather than stage rouge.

It may be reassuring for footloose capital that New Labour is now a coalition defined by interests rather than a crusade driven by ideas, a party that business can do business with. But, contrary to fashionable opinion, it is ideology that gives parties the disci- pline to govern. It is ideology's absence, not its dominance, that has seen the Tory Party that won a landslide in 1987 reduced to a series of bickering baronies in 1997.

Abandoning ideology has not made Labour less factional, it has simply caused factions to coalesce around individuals rather than platforms. Power may be a use- ful sedative for dissenters, but when trou- bles come and the banner of revolt is raised Blair may come to regret ditching a more potent opiate — Labour's old religion.

The author writes for the Times.

Previous page

Previous page