ARTS

Exhibitions

Dreams of a Summer Night L'Amour fou (Hayward Gallery till 5 October) The Human Touch (Fischer Fine Art till 8 August)

A dream come true

Giles Auty

In a world in which dealers regularly earn more by picking up a telephone than do artists by picking up their brushes some 300 clays a year, values become as elusive as soap in a bath. What does international artistic stature owe simply to exposure, or high cost to little more than scarcity value? On 6 July, in a Sunday Times Magazine feature on de Kooning, John McEwen, my respected predecessor at this weekly, made an interesting claim: 'Price of the work is the gauge of artistic stature and de Koon- ing has been the most bankable living artist since November 1, 1984 when Christie's auctioned a small oil painting by him. "Two Women" fetched £1,596,774, a new world record sum for a work by a living artist.'

I do not share John's faith in the significance of the marketplace; experience suggests that the market forces which determine prices for the works of living artists seldom have much to do with absolute worth. Among these forces, national pride may have little less bearing than artistic ability; usually works of art are valued more highly, in terms of criticism and money, in their countries of origin. Even in a major cultural crossroads such as London, opportunities to see the art of other nations may still depend, in part, on the power, influence and cultural aggres- siveness of the countries concerned. Visitors to one of the two current Hay- ward Gallery shows, Dreams of a Summer Night, may guess rightly that ThOrarinn B. Thorlaksson was born not merely north of Watford but north of most other inhabited regions also. As Iceland's lone representa- tive in a large-scale exhibition of turn-of- the-century painting from Scandinavia, his name and work will have been unfamiliar so far to more or less everyone in Britain.

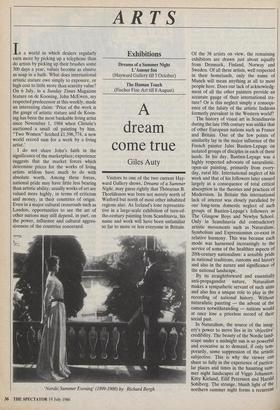

`Nordic Summer Evening' (1899-1900) by Richard Bergh Of the 38 artists on view, the remaining exhibitors are drawn just about equally from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Of all these artists, well respected in their homelands, only the name of Munch will mean anything at all to most people here. Does our lack of acknowledg- ment of all the other painters provide an accurate gauge of their international sta- ture? Or is this neglect simply a consequ- ence of the falsity of the artistic fashions formerly prevalent in the Western world?

The history of visual art in Scandinavia during the late 19th century was unlike that of other European nations such as France and 13ritain. One of the few points of similarity lay in the major influence of the French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage on isolated groups of disciples in each of these lands. In his day, Bastien-Lepage was a highly respected advocate of naturalistic, open-air painting, primarily from every- day, rural life. International neglect of his work and that of his followers later ensued largely as a consequence of total critical absorption in the theories and practices of Modernism. In Britain this international lack of interest was closely paralleled by our long-term domestic neglect of such groups of Bastien-Lepage's followers as The Glasgow Boys and Newlyn School. Only in Scandinavia did contradictory artistic movements such as Naturalism, Symbolism and Expressionism co-exist in relative harmony. This was because each mode was harnessed increasingly to the service of some of the healthier aspects of 20th-century nationalism: a sensible pride in national traditions, customs and history and also in the nature and significance of the national landscape. By its straightforward and essentially anti-propagandist nature, Naturalism makes a sympathetic servant of such aims and also has a unique role to play in the recording of national history. Without naturalistic painting — the advent of the camera notwithstanding — nations would at once lose a priceless record of their social past.

In Naturalism, the source of the imag- ery's power to move lies in its 'objective' credibility. The beauty of the Nordic land- scape under a midnight sun is so powerful and evocative as to demand, if only tem- porarily, some suppression of the artistic subjective. This is why the viewer can share so fully in the experience of particu- lar places and times in the haunting sum- mer night landscapes of Viggo Johansen, Kitty Kieland, Eilif Peterssen and Harald Sohlberg. The strange, bluish light of the northern summer night forms a recurrent

link not only between Naturalistic but also certain of the more Expressionistic and Romantic artists. It is this light which sets the rare, tranquil mood of Munch's 'Inger on the Beach' Eugene Jansson's `Riddaf- Arden in Stockholm' and Richard Bergh's `Nordic Summer Evening', one of the great masterpieces of its era.

This wonderful exhibition provides further proof of my frequently stated con- tention that supposedly international col- lections of modern art, in Britain and elsewhere, have been far too narrow in their scope. It is extraordinary that the work of artists of the stature of Harriet Backer, Pekka Halonen or Vilhelm Ham- tnershoi, or those already mentioned, has never previously — with the exception of Munch -- been seen here. The paintings of Unfits Andersen Ring and Prince Eugen, the youngest son of the Swedish King Oscar II, were also a revelation.

Shows such as this make the best use of public and private resource; Volvo have made an extremely generous contribution to the costs of this exhibition. The finest possible follow-ups would be exhibitions of American and Italian 19th-century art which could prove similar eye-openers for the modern-art historians of Britain. No doubt General Motors and Fiat would be delighted to follow Volvo's example. Not content with putting on one excel- lent exhibition, the Hayward's manage- ment have excelled themselves on this occasion by showing also L'Amour fou, a Collection of Surrealist photographs. Photography strikes me as often being a more suitable vehicle than painting for Surrealist imagery. A good deal of Surreal- ist painting is contrived and irritating; indeed, the premise that the workings of the subconscious mind are more interesting than those of the conscious seems a pretty odd one, in the first place. Man Ray's black and white photographs, many featur- ing the beautiful Lee Miller, achieve a level of sophistication and elegance never attained in the coloured artefacts of Dali and Magritte. Dreams of a Summer Night and L' Amour fou are two exhibitions no one should miss. Both have excellently pro- duced catalogues. Dr John House's clear, modest and sensible essay in the former is in contrast to some of the writing in the latter, which ensnares its readers in the labyrinthine complexities of North Amer- ican academic prose.

In a month when many galleries begin their summer wind-down with 'anthology' exhibitions, it is refreshing to find a thoughtfully selected show featuring the work of promising young artists. At Fisch- er Fine Art (30 King Street, SW1) Mary Touch, Beaumont presents The Human

,

Ouch, a selection which includes such interesting painters as Jacinto Feeney and Ansel rut. All aspiring ir endeavoKur to get themselvestists bornshould with equally memorable names.

Previous page

Previous page