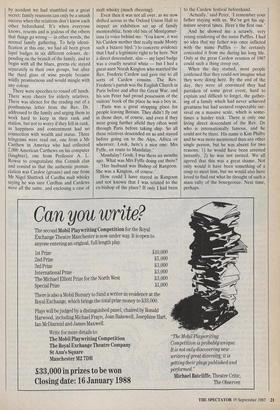

GATHERING OF THE CARDEWS

The most extraordinary

family reunion Miles Kington has ever been to LAST Saturday, 12 September, about 170 descendants of the Rev. Cornelius Cardew gathered at Exeter College, Oxford, to give thanks to the old boy's memory, have a day out together and meet each other for the first time. It was the most extraordin- ary family reunion I have ever been to. There was a feeling throughout the day that Cardew must have been quite a character for nearly 200 relations to get together two centuries after his coat of arms was granted (how many readers could muster 20, let alone 200 living cousins?) but in his 85 years from 1748 to 1831 Cardew never rose much higher than Mayor of Truro and Chaplain in Ordinary to the Prince of Wales. Thousands of Englishmen have done much better and had as many descendants.

The extraordinary difference between him and the others lies not in him, but in his descendants, who have kept track of each other in an obsessively tenacious way. There were few people in uniform last Saturday, just one naval engineer and a clergyman who took the service with which the day kicked off, but old Cornelius would have approved of the setting otherwise. Very Church of England, as we filled Exeter's stained-glass chapel and some of us knelt as we all prayed. Very Oxford, as we filled Exeter's hall for lunch and read each other's lapel badges. Very middle class indeed, as we swapped addresses, useful contacts, tips about the new Peugeot and job information. But what would he have made of some of the details?

`I'm working in a small firm which takes sandwiches round to yuppies in the City at lunchtime. No time to go out for them- selves, of course — all tied to their phones.' This from a young female Car- dew. 'You'd think with all that money they'd choose nice sandwiches, but it's all corned beef and cheese 'n' pickle. Funny thing is that there's a shoe-shine boy going round as well, and he shines their shoes as they're actually on the phone. Weird.'

`I run a small family hotel in Bellagio on Lake Como,' says the lady next to me in chapel. I squint at her lapel badge. Her name is now Leoni. Is her husband any relation to the Soho restaurant Leoni's Quo Vadis? She smiles. 'No, but funnily enough my husband knows them; they were all interned together on the Isle of Man during the war.'

`I hadn't ridden a bicycle since my childhood, but I got on one two years ago and found that I could still remember how to ride it. Unfortunately, I had forgotten how to stop and get off it.' This from a painter called Simon Fox, who has a Cardew grandmother and has just refused his third glass of champagne, waiting for the orange juice. 'Actually, I'm very unin- terested in all the clergymen and generals the Cardews kept producing — for me, by far the greatest member of the family was the potter, Michael Cardew. I recently badgered the Ashmolean into putting some of his stuff on display. Yes, he was a great man.'

`I used to be in two-man submarines,' says Marcus Cardew sitting next to me at lunch. 'Great fun. Time absolutely flies in a two-man sub, you've no idea.' He's right. I had no idea. 'Then I rented out unman- ned subs for a while, but I've ended up in the Lake District designing things. What things? Any things. Look if you're ever up that way, drop in at the Porthole in Bowness and see us — it's wonderful Italian cooking, so we've made it our works canteen.'

He gave me his card. His full name is Marcus St Erme Cardew. St Erme is the name of the original parish in Cornwall of which the Rev. Dr was the incumbent and all Marcus's four brothers, except, I think, one, still have St Erme as a second name. He pronounces it Snerme. Better than Snaustell, anyway, he says. I give him my card, even though it features a house I have just moved out of and a newspaper I have just left.

`Don't worry,' says Marcus. 'Why not ask my wife, Solveig here, to redesign you a new card? She's a graphic designer.'

It was by now halfway through lunch and from the hubbub you would think we had known each other for ever. In fact, I met nobody who had known more than half a dozen previously, and even the organiser (Michael Cardew, chartered accountant of Lewisham) didn't know many by sight, but by accident we had stumbled on a great secret: family reunions can only be a smash success when the relations don't know each other beforehand. It's when everyone knows, resents and is jealous of the others that things go wrong in other words, the normal family gathering. To help identi- fication at this one, we had all been given lapel badges in six different colours, de- pending on the branch of the family, and to begin with all the blues, greens etc stayed separately in their own groups, but after the third glass of wine people became wildly promiscuous and would mingle with any colour.

There were speeches to round off lunch. There were cheers for elderly relatives. There was silence for the reading out of a posthumous letter from the Rev. Dr, addressed to the family and urging them to work hard to keep in their rank and station, but not to worry if they fell in rank, as happiness and contentment had no connection with wealth and status. Three telegrams were read out, one from a Mr Carthew in America who had collected 2,000 American Carthews on his computer (laughter), one from Professor A. L. Rowse to congratulate this Cornish clan and remind us that the authentic pronun- ciation was Cardew (groans) and one from Mr Nigel Shattock of Cardhu malt whisky saying he was sure Cardhus and Cardews were all the same, and enclosing a case of

malt whisky (much cheering). .

Even then it was not all over, as we now drifted across to the Oxford Union Hall to inspect an exhibition set up of family memorabilia, from old bits of Montgomer- iana (a voice behind me: You know, it was his Cardew mother that really made Monty such a bizarre bird.') to concrete evidence that I. had a legitimate right to be here. Not a direct descendant, alas — my lapel badge was a cruelly neutral white — but I had a great-aunt Norah Kington who married the Rev. Frederic Cardew and gave rise to all sorts of Cardew cousins. The Rev. Frederic's parish was the English Church in Paris before and after the Great War, and his son Peter had proud possession of the visitors' book of the place he was a boy in.

`Paris was a great stopping place for people leaving Britain. They didn't fly out in those days, of course, and even if they were going further afield they often went through Paris before taking ship. So all these relatives descended on us and stayed before going on to the Alps, Africa or wherever. Look, here's a nice one: Mrs Fyffe, en route to Mandalay.'

Mandalay? Gosh, I was there six months ago. What was Mrs Fyffe doing out there?

`Her husband was Bishop .of Rangoon. She was a Kington, of course.'

How could I have stayed in Rangoon and not known that I was related to the ex-bishop of the place? If only I had been to the Cardew festival beforehand.

`Actually,' said Peter, 'I remember your father staying with us. We've got his sig- nature several times. Here's the first one.'

And he showed me a scrawly, very young rendering of the name Puffles. I had no idea that my father was once inflicted with the name Puffles — he certainly concealed it from me during his long life. Only at the great Cardew reunion of 1987 could such a thing creep out.

When the day started, most people confessed that they could not imagine what they were doing here. By the end of the day, they were all convinced they had partaken of some great event, hard to explain and difficult to forget, the gather- ing of a family which had never achieved greatness but had secured respectable sur- vival on a massive scale, which is some- times a harder trick. There is only one living direct descendant of the Rev. Dr who is internationally famous, and he could not be there. His name is Kim Philby and he was more mentioned than any other single person, but he was absent for two reasons: 1) he would have been arrested instantly, 2) he was not invited. We all agreed that this was a great shame. Not only would it have been something of a coup to meet him, but we would also have loved to find out what he thought of such a mass rally of the bourgeoisie. Next time, perhaps.

Previous page

Previous page