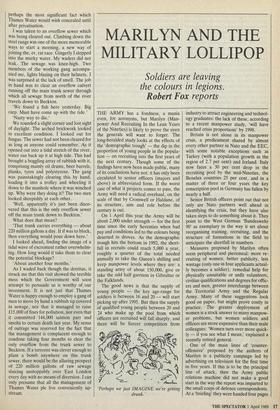

MARILYN AND THE MILITARY LOLLIPOP

Soldiers are leaving the colours in legions.

Robert Fox reports

THE ARMY has a fondness, a mania even, for acronyms, but Marilyn (Man- power And Recruiting In the Lean Years of the Nineties) is likely to prove the siren the generals will want to forget. The long-heralded study looks at the effects of the 'demographic trough' — the dip in the proportion of young people in the popula- tion — on recruiting into the first years of the next century. Though some of the findings have now been made public, many of its conclusions have not: it has only been circulated to senior officers (majors and above) in abbreviated form. If the worst case of what it projects comes to pass, the Army will need a radical overhaul, on the scale of that by Cromwell or Haldane, of its structure, aim and role before the century is out.

On 1 April this year the Army will be about 2,000 under strength — for the first time since the early Seventies when bad pay and conditions led to the colours being deserted in droves. As the demographic trough hits the bottom in 1992, the short- fall in recruits could reach 5,000 a year, roughly a quarter of the total needed annually to take the Queen's shilling and keep manpower levels where they are: a standing army of about 150,000, give or take the odd half garrison in Gibraltar or the Falklands.

The good news is that the supply of young people — the key age-range for soldiers is between 16 and 20 — will start picking up after 1995. But then the supply of qualified young people between 20 and 24 who make up the pool from which officers are recruited will fall sharply, and there will be fiercer competition from 'Perhaps we just IMAGINE we're getting drunk.' industry to attract engineering and technol- ogy graduates: the lack of these, according to a recent manpower study, 'will have reached crisis proportions' by 1998.

Britain is not alone in its manpower crisis, a predicament shared by almost every other partner in Nato and the EEC, with some notable exceptions such as Turkey (with a population growth in the region of 2.7 per cent) and Ireland. Italy now faces a 30 per cent drop in the recruiting pool by the mid-Nineties, the Benelux countries 25 per cent, and in a matter of three or four years the key conscription pool in Germany has fallen by nearly a half.

Senior British officers point out that not only are Nato partners well ahead in identifying the crisis, but they have also taken steps to do something about it. They point to the West German 'Bundeswehr 90' as exemplary in the way it set about reorganising training, recruiting, and the structure of formations in the field to anticipate the shortfall in numbers.

Measures proposed by Marilyn often seem peripheral and piecemeal: more re- cruiting of women, better publicity, less wastage (only one in four applicants actual- ly becomes a soldier), remedial help for physically unsuitable or unfit volunteers, civilian qualifications and degrees for offic- ers and men, greater interchange between the Territorial Army and the Regular Army. Many of these suggestions look good on paper, but might prove costly in practice. The greater deployment of women is a stock answer to many manpow- er problems, but women soldiers and officers are more expensive than their male colleagues: 'Women turn over more quick- ly — if you see what I mean,' explained a recently retired general.

One of the main lines of 'counter- offensive' proposed by the authors of Marilyn is a publicity campaign led by advertising on television for the first time in five years. If this is to be the principal line of attack, then the Army public relations machine did not make a good start in the way the report was imparted to the small corps of defence correspondents. At a 'briefing' they were handed four pages of notes, a graph and an article in the Army's house magazine, Soldier, which included an interview with the drafters of Marilyn: it also included a glaring factual error — suggesting that only Greece in Nato will suffer no demographic decline. Despite repeated requests no senior figure from the Defence Staff or the Army directorates was available for comment.

The reason for this coyness seems not to lie in Marilyn, who could claim like a famous alter ego, Sugar Cane in Some Like It Hot, 'I'm not very bright really — I just seem to get the fuzzy end of the lollipop.' The present shortage of manpower in the Army — the drop of 2,000 plus in a year has little to do with the onset of the demographic trough but much with the problem of retention. All three armed services are now afflicted by a serious haemorrhage of qualified NCOs and middle-range officers: in the military ver- nacular, the lads, in the Rhine Army especially, are stampeding to buy them- selves out. According to one report an infantry battalion stationed at Minden has recently mothballed 15 of its Armoured Personnel Carriers as it is now one com- pany — some 120 men — short: furth- ermore some 150 to 200 more of the battalion are said to have applied for Premature Voluntary Retirement. Reasons for leaving vary from complaints about housing and schools allowances to wives unwilling to sacrifice promising careers for long tours in Germany — for an armoured regiment this can now mean up to 15 years.

The Marilyn debate touches a much larger question facing the British armed forces. Why and in what form, if at all, will they be required in the 21st century? This at least seems to be one of the principal spectres at the feast of the present crisis over manpower and recruitment.

In evidence to the House of Commons Defence Committee the Government com- mitted itself to the deployment of 55,000 service personnel to Nato in Europe for 50 years under the Brussels Protocols ratified in 1954. But this invites a practical and political question. With the manpower crisis now upon Britain and her neighbours how will the concept of the Nato Northern Army Group be sustained? This was the notion designed by General Sir Nigel Bagnall of one large army to deliver a massive counter-punch in the flank of any Warsaw Pact armoured thrust across the north German plain.

There is a second, more important, political question — otherwise known as the 'Corby factor'. With the INF Treaty and the Gorbachev peace offensive, doubts are increasing in the minds of potential and actual recruits about the need for a heavy Nato ground presence in Germany. In Germany itself this has led to restrictions on exercise and deployment. British tank units are now reduced to 450 track miles per armoured vehicle per year. Whatever the nice calculations of strategic and con- ventional arms control, for the young blades of the cavalry being in Germany is becoming a bit of a bore.

But while we are facing a decline in the army's human resources there is a demog- raphic bulge in the populations around the fringes of Europe. Most Nato planning as far as this country and the northern Euro- pean allies are concerned, the US and Canada included, is rather like the Prus- sian tactics at Jena in 1806, where Napo- leon overcame an army brought up on the methods of Frederick the Great 50 years before. Nato is predicated largely on an east-west confrontation across northern Europe — now becoming an increasingly less 'likely scenario. The real pressure on industrialised western Europe is from the south and east, the Maghreb and the Levant where populations will double in 30 years. In the ancient world, the historian Polybius described a similar phenomenon to explain the roots of the north-south contest between Rome and Hannibal's Carthage, the lengthy slugging match known as the Punic wars.

Robert Fox is the Defence Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page