Exhibitions

Egon Schiele and His Contemporaries (Royal Academy, till 17 February)

Schiele appeal

Giles Auty

iven the extraordinary reputation of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele in the non-German-speaking world today — one that surely rivals that of Van Gogh and the leading Impressionists. . . .' So begins the foreword written by Norman Rosenthal to

`G

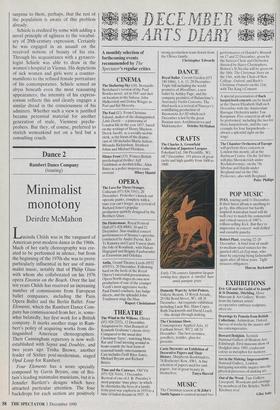

Egon Schiele's typically anguished 'Self- portrait, Pulling a Face', 1910 the substantial catalogue accompanying Egon Schiele and His Contemporaries, the new exhibition at the Royal Academy. Any who thought Schiele's main body of artistic admirers lay principally among morbid adolescents may be somewhat sur- prised to find his reputation placed along- side that of Van Gogh by no less rounded a man than the exhibitions director of the Royal Academy. Two further mysteries exist in why an Austrian's reputation should be thought to attain its dizziest heights among non-German-speakers and why Van Gogh should find himself brack- eted with leading Impressionists.

So much for mysteries. The current show is from the Leopold Collection in Vienna and mingles familiar artists such as Klimt, Kokoschka and Schiele with others much less renowned, some may think deservedly so. However, Richard Gerstl, for instance, is credited by Norman Rosenthal with being 'an extraordinarily talented painter whose work seems to foreshadow both the concerns and techniques of many of the Neo-Fauve painters of the 1980s . . Yawns all round. Gerstl had an affair with the wife of the composer Arnold Schoen- berg, admittedly, leading to suicide at the early age of 25, but seems unremarkable otherwise. Had his small painting 'Meadow with Houses in the Background' been painted in 1988 by a little-known 25-year- old from Ventnor rather than some 80 years earlier by one from Vienna I doubt it would excite the interest of anyone at all, least of all Norman Rosenthal.

Klimt is represented in the Leopold Collection principally by drawings of a decorative eroticism. He was a masterly draughtsman who chronicled that far dis- tant time when young male heterosexuals were still almost as obsessed with prom- iscuous sexual practice as their male homosexual counterparts of today. Klimt's allegorical paintings, of which 'Death and Life' is a notable example, have the famil- iar patchwork ornateness which characte- rised his wonderful series of portraits. The collection boasts, too, one of Klimt's re- latively rare and hauntingly mysterious landscapes, 'The Large Poplar'. I enjoyed similarly the half-dozen or so flattened townscapes by Schiele which remove his subject matter just occasionally from gri- macing, posturing, attenuated renderings of his own face and body. Schiele's morbid, though possibly subconscious desire to shock presupposed both an audience and an effect. In his own short lifetime his audience responded by imprisoning this talented young artist for 24 days. Now we are unshockable, of course, and pride ourselves wrongly on being so.

Schiele is presented tacitly as the star of the current exhibition, not least for the inapposite parallels some care to draw between his work as a pioneer of anguished Expressionism and the generally vapid, neo-Expressionist art which has come out of Germany in recent years. Schiele's anguish was genuine, at least, even though its expression was frequently sentimental. Perhaps it is worth reflecting on the com- parison made earlier with Van Gogh who also died young after a working life of only a decade and who came likewise from a family with a history of insanity. Here Schiele's natural skills are clearly the more obvious and remarkable. His wiry line and sense of design show precocious graphic ability although his drawing is not always as certain as many of his admirers imagine. From its early stages, Schiele's vision is infused with melancholy and the shadow of death, whereas Van Gogh struggles robust- ly and heroically to keep his demons at arm's length. Already a fresh sight of Schiele's work has prompted much porten- tous philosophising by art critics about the certainty of death. It may come as a surprise to them, perhaps, that the rest of the population is aware of this problem already.

Schiele is credited by some with adding a novel principle of ugliness to the vocabul- ary of 20th-century expression. Certainly he was engaged in an assault on the received notions of beauty of his era. Through his acquaintance with a gynaeco- logist Schiele was able to_ draw in the women's hospital in Vienna. His depictions of sick women and girls were a counter- manifesto to the refined female portraiture of his contemporaries. Schiele sensed an abyss beneath even the most reassuring appearances; the intensity of his express- ionism reflects this and clearly engages a similar dread in the consciousness of his admirers. Whether such a view is justified became perennial material for another generation of male, Viennese psyche- probers. But they, of course, preferred to stretch womankind not on a bed but a consulting couch.

Previous page

Previous page