Exhibitions

Amazons of the Avant-Garde (Royal Academy, till 6 February)

Russian radicalism

Andrew Lambirth

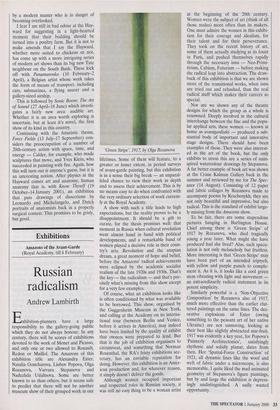

Exhibition-planners have a large responsibility to the gallery-going public which they do not always honour. In any century, there will be scores of exhibitions devoted to the work of Monet and Picasso, and only one or two allowed to Rouault, Redon or Maillol. The Amazons of this exhibition title are Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova and Nadezhda Udaltsova. Some are better known to us than others, but it seems safe to predict that there will not be another museum show of their grouped work in our `Green Stripe, 191Z by Olga Rozanova lifetimes. Some of them will feature, to a greater or lesser extent, in period surveys of avant-garde painting, but this exhibition is in a sense their big break — an unparal- leled chance to view their work in depth and to assess their achievement. This is by no means easy to do when confronted with the very ordinary selection of work current- ly at the Royal Academy.

A show with such a title leads to high expectations, but the reality proves to be a disappointment. It should be a gift to curate, for the thesis promises well: that moment in Russia when cultural revolution went almost hand in hand with political developments, and a remarkable band of women played a decisive role in their coun- try's arts. Revolution and the utopian dream, a great moment of hope and belief, before the Amazons' radical achievements were eclipsed by the academic socialist realism of the late 1920s and 1930s. That's the key — the radicalism — and that's pre- cisely what's missing from this show except for a very few examples.

Of course, what an exhibition looks like is often conditioned by what was available to be borrowed. This show, organised by the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and calling at the Academy on its interna- tional tour (between Berlin and Venice, before it arrives in America), may indeed have been limited by the quality of exhibit that owners were prepared to lend. But that is the job of exhibition organisers to circumvent, and something that Norman Rosenthal, the RA's feisty exhibitions sec- retary, has an enviable reputation for doing. However, this exhibition is an Amer- ican production and, for whatever reason, it simply doesn't deliver the goods. Although women occupied important and respected roles in Russian society, it was still no easy thing to be a woman artist at the beginning of the 20th century. Women were the subject of art (think of all those nudes) more often than its makers. One must admire the women in this exhibi- tion for their courage and idealism, for their talent and for their perseverance. They took on the recent history of art, some of them actually studying at its fount in Paris, and pushed themselves rapidly through the necessary isms — Neo-Primi- tivism, Cubism, Futurism — before making the radical leap into abstraction. The draw- back of this exhibition is that we are shown more of the transitional works, when isms are tried out and rehashed, than the real radical stuff which makes their careers so special.

Nor are we shown any of the theatre designs for which the group as a whole is renowned. Deeply involved in the cultural interchange between the fine and the popu- lar applied arts, these women — known at home as avantgardistki — produced a sub- stantial body of important and innovative stage designs. There should have been examples of these. They were also interest- ed in the art of the book, but the only exhibits to stress this are a series of unin- spired watercolour drawings by Stepanova. A far better example of book art was shown at the Crane Kalman Gallery back in the summer and reviewed by me for The Spec- tator (14 August). Consisting of 12 paper and fabric collages by Rozanova made to accompany poems by Kruchenykh, they are not only beautiful and impressive, but also radical. This is the standard of exhibit large- ly missing from the Amazons show.

To be fair, there are some stupendous pictures hanging in Burlington House. Chief among these is 'Green Stripe' of 1917 by Rozanova, who died tragically young a year later. What might she have produced had she lived? Alas, such specu- lation is not only melancholy but fruitless. More interesting is that 'Green Stripe' may have been part of an intended triptych, with yellow and purple panels to comple- ment it. As it is, it looks like a cool green stem vibrating with light and movement an extraordinarily radical statement in its potent simplicity.

Similarly powerful is a Non-Objective Composition' by Rozanova also of 1917, much more effective than the earlier clut- tered paintings on the same lines. The dec- orative explosions of Exter (owing something to the peasant art of her native Ukraine) are not unmoving, looking at their best like slightly abstracted star-fruit. 1917 was evidently a key year, for Popova's `Painterly Architectonics', satisfyingly rhythmic and solidly planar, dates from then. Her 'Spatial-Force Construction' of 1921, all dynamic lines like the woof and weft of fabric under a microscope, is also memorable. I quite liked the mad animated geometry of Stepanova's figure paintings, but by and large the exhibition is depress- ingly undistinguished. A sadly wasted opportunity.

Previous page

Previous page