2. Algerian crisis

Mr Heath could have been forgiven for dreaming that France might handle Britain over the Common Market with the same patience, forbearing, and willingness to meet her three quarters of the way that she had displayed towards Algeria since 1962, and especially in the past eighteen months. The Brussels negotiations would have become a real diplomatic picnic.

There was a time when France had been as inextricably involved with Britain as she was later to become with Algeria. Unfor- tunately, someone noted in a very different context, there had also been Joan of Arc.

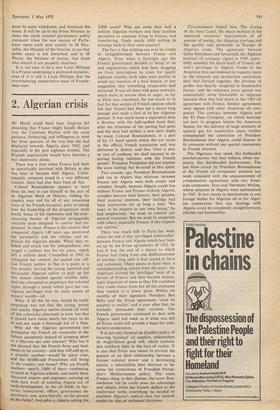

Colonel Boumedienne appears to have done his best to cast himself in the part of an Algerian Maid of Orleans, ridding his country once and for all of any remaining trace of the French occupant, prior to taking over the leadership of the progressive Arab world. Some of his statements and the ever- recurring themes of Algerian propaganda certainly seem designed to convey that im- pression. In them, Prance is the country that conquered Algeria 140 years ago, destroyed her personality and her culture, and ex- ploited the Algerian people. When they re- belled and struck out for independence, she waged a ruthless war for six years, which left a million dead. Compelled in 1962 to relinquish her control, she caused one mil- lion French settlers to flee in a panic in a few months, leaving the young, battered and devastated Algerian nation to pick up the bits almost unaided against terrible odds. And she attempted to perpetuate her colonial rights through a treaty which gave her out- rageous privileges over its main source of natural wealth—oil.

What, if all this be true. would be really surprising was not that the young, proud and touchy Algerian nation should rid itself of this colonialist aftermath in turn; but that it should have taken nearly ten years to do so and .not made a thorough job of it then.

Why did the Algerian government not nationalise the French oil companies in the Sahara completely instead of stopping short at a fifty-one per cent interest? Why has it not decreed that the French firms and busi- nesses in the country—and they still add up to a sizeable number—would 'be taken over, and the 60,000-odd Frenchmen still living in the country sent home? Why are French teachers—nearly 5,000 of them—continuing to teach in Algerian schools; and nearly three thousand experts and engineers carrying on with their work of assisting Algeria out of underdevelopment, in the oil fields, in fac- tories, laboratories, offices, government de- partments, and, quite literally, on the ground in the fields? Ancl,why is Algeria asking for.

2,000 more? Why are more than half a million Algerian workers and their families permitted to continue living in France, and transferring freely nearly £800 million in earnings back to their own country?

The fact is that nothing can ever be simple or straightforward between France and Algeria. Even when a fortnight ago the French government decided to bring to an end negotiations which had been dragging on from interruption to crisis for nearly eighteen months, both sides were careful to avoid any mention of a final breach, or any suggestion that something irreparable had occurred. It was all done with great restraint, much more in sorrow than in anger, as far as Paris was concerned, far too much so in fact for that section of French opinion which felt that France had been led a dance long enough and made a fool of by her Algerian partner. It was much more a separation than a divorce, with the half-spoken hope that, after the bitterness of the parting had gone and the dust had settled, a new start might be made. Colonel Boumedienne, in a part of his 13 April speech which did not occur in the official French translation and was delivered in dialect, said that 'after a year or two of coolness, we shall succeed in re- storing lasting relations with the French people.' President Pompidou did not express the same feeling; but he acted in that spirit. Two months ago, President Boumedienne told me in Algiers that relations between France and Algeria were both simple and complex. Simple, because Algeria could live without France and France without Algeria; complex because their history, their peoples, their material interests, their feelings had been interwoven for so long a time. 'We want to be masters in our own house,' he had emphasised, 'we want to control our natural resources. But we want to cooperate with others, especially France, if she respects our options.'

There was much talk in Paris last week about the end of that 'privileged relationship' between France and Algeria which had been set up by the Evian agreements of 1962. In fact it was the end of a dream to which France had clung from one disillusionment to another, long after it had ceased to have any substance. There seems to have been a misunderstanding almost from the start : the Algerians claimed the 'privileges' were all in favour of France, and they became increas- ingly impatient of them as they felt confident they could obtain from her all the assistance they needed at a lower price. Within six months of their signature, President Ben Bella said the Evian agreements 'must be adapted to reality', and a year after that, he formally demanded their revision. The French government continued to deal with Algeria until last week as if what was left of Evian could still provide a basis for satis- factory cooperation.

It is not only General de Gaulle's policy of insuring 'national' oil supplies, independent of Anglo-Saxon good will, which explains this stubborn fight in the face of reality. It is also that Evian was meant to provide the pattern of an ideal relationship between a former colonial power and a developing nation, a relationship later destined to be- come the cornerstone of President Pompi- dou's Mediterranean policy. The more France clung to this illusion, the more Bou- medienne felt he could press his advantage and obtain, while the French dallied at the conference table, everything he needed to establish Algeria's control over her natural ,wealth by dint of unilateral decisions. Circumstances helped him. The closing of the Suez Canal, the sharp increase in the industrial countries' requirements of all sources of energy, the shipping shortage and the quality and proximity to Europe of Algerian crude. The agreement between Getty Petroleum and Sonatrach, the Algerian national oil company, signed in 1969, appar- ently sounded the death-knell of French oil- men's privileges in Algeria. Under it, the American firm surrendered its majority share in the research and production association they had formed together, the division of profits was heavily weighted in Sonatrach's favour, and the reference price agreed was substantially more favourable to Algerian interests than that laid down in the 1965 oil agreement with France. Similar agreements were signed with other American oil com- panies. The contract between Algeria and the El Paso Company, on which hearings are now in progress before the American Senate. for the delivery of huge amounts of natural gas for twenty-five years, further strengthened the conviction of President Boumedienne that Algeria could dispose of its resources without any special concessions to French interests.

The Algerians may speak like hotheaded revolutionaries; but they behave, when nec- essary, like hardheaded businessmen. The last blow struck by President Boumedienne at the French oil companies' position last week coincided with the announcement of compensation agreements with two Amer- ican companies. Esso and Newmont Mining, whose interests in Algeria were nationalised in 1967. It was meant to demonstrate to any foreign bidder for Algerian oil or for Alger- ian cooperation that any dealings with Algeria could be completely straightforward, reliable and businesslike.

Previous page

Previous page