FINANCE-PUBLIC & PRIVATE.

[BY OUR CITY EDITOR.]

REPARATIONS AND DEBT ENTANGLEMENTS.

[To the Editor of the SPECTATOR.] SIR,—It is, of course, beyond my province to discuss the political aspects of the French Reply to the British Note, but, concerning certain of the purely financial matters raised, I should like to attempt to deal with a few points which the ordinary public may, perhaps, find some difficulty in following.

A point in the French Reply which has given some offence to the City is the cool reception given to the considerable sacrifice made by this country in the matter of its claims upon our debtors. It will be remembered that, so far as Belgium is concerned, all claims for the repayment of credits advanced have been surrendered, but, as regards our other European Allies, the position, as outlined at the time of our last Budget, may be sum- marized as follows :— •

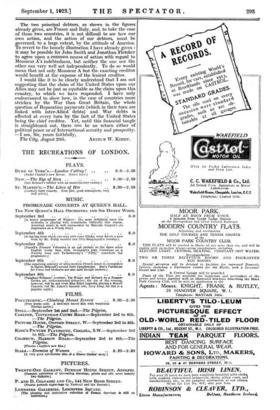

Russia • • • • • • £668,199.000 France .. £601,645,000 Italy .. 2527,865,000 Serb-Croat-Slovene Kingdom £26,194,000 Portugal, Roumania, Greece

and other Allies .. £70,057,000 £1,913,960,000

It will be seen, therefore, that apart from Russia, the indebtedness to us of our European Allies exceeds £1,200,000,000. Great Britain, however, in her Note to France, made it clear that we should be satisfied if we received a sum sufficient to meet our engagements to the United States which, capitalized, represents a total of 1710,000,000. Not only so, but we expressed our willing- ness to count in anything which we received in the shape of Reparations from Germany. In other words, if we obtained from that country the whole amount to which we are entitled, the indebtedness of our Allies would be wiped out. The generous character of this offer was duly recognized in the Reply from Belgium, and the lack of appreciation, indeed, the almost discourteous reception of the offer by France, has made a profound impression in financial circles. In a moment I will mention one point which partially explains the French attitude but all the same, it does not explain the scant acknowledg- ment made of the generous offer on our part.

In passing, however, I cannot forbear from commenting upon the typical treatment of the matter by Mr. Lloyd George, in his article last week to certain of the daily newspapers. That astute politician is evidently more concerned in embarrassing the Government in power than in relieving any temporarily strained relations between France and this country. In the course of his article, Mr. Lloyd George said,." M. Poincare may not be able to extract Reparations out of Germany, but in seven months he has succeeded in forcing 290 millions out of Great Britain." In other words, Mr. Lloyd George insinuates that Mr. Baldwin's Government is not merely showing generosity, but is being brow-beaten by France into making undue concessions at the expense of the British taxpayer. As usual, however, when it comes to a question of facts and figures, rather than allusions to mountain tops" and rare and refreshing fruits," Mr. Lloyd George fails in the matter of accuracy. Earlier in his article he reminds his readers that Lord Balfour, in his famous Note to the Allies when offering to forgo all claims for inter-Allied debts and Reparations if Britain were secured against payment of the American debt, calculated that debt at one thousand millions, whereas the Curzon Note dealt with the matter on the basis of 710 millions. That, apparently, is where Mr. Lloyd George gets his further sacrifice of 290 millions. The explanation, of course, is that at the time when Lord Balfour's Note was despatched, the American debt in terms of annual payments was calculated on a 5 per cent. basis, and the reduction to 710 millions is due to the subsequent process of adjustment in consequence of the lower terms of interest on which the American debt has been funded. That is to say, the concession now made in Lord Curzon's Note is virtually identical with that of the Balfour Note, of which Mr. Lloyd George so highly approves, the only difference, perhaps, being that the Balfour Note was couched in terms which led to temporary serious misunderstandings between America and this country. While, however, the City regrets the lack of courteous appreciation of the British offer displayed in the French Reply, there is one aspect of this problem of inter-Allied debts which may well make it difficult for France either to close quickly with the British offer or to display the gratitude and pleasure which might be anticipated. I would like to make the point quite dear, because it has a practical and important bearing upon the whole problem of inter-Allied debts, which, in its turn, must affect International political and financial relations for many a year to come. Let me put the matter in somewhat, homely fashion. If Monsieur A, in France, who is in anything but a prosperous condition, owes to John Smith of England the sum of 120,000, and receives a letter from Smith sug- gesting an early settlement on the basis of 110,000, he may be rather hampered in his reply, if it so happens that he owes to Jonathan Fletcher, a somewhat exacting creditor in New York, the sum of 130,000. He may say to himself, "This is a very fair and even a generous offer on the part of John Smith, but if I accept it openly and attempt to effect an early settlement, what about the effect upon Jonathan Fletcher ? Can I be sure that he will be equally generous, or may I not run the chance of bringing down upon me a demand from Jonathan Fletcher for his full pound of flesh, especially as Jonathan Fletcher and John Smith, while good friends enough, happen to be competitors in business ? " Under such circumstances, it would not be very surprising if Mon- sieur A were to feel that until he is sure of the nature of the demand to be made upon him by Jonathan Fletcher, he has nothing for it, in his somewhat straightened cir- cumstances, but to protest to John Smith that he has difficulty, until he is in more comfortable circumstances, of even meeting this reduced demand. In other words, we are up against the old difficulty of the United State3 being at the centre of this problem of inter-Allied debts. Although our attitude was, not unnaturally, misunder- stood at the time, it is, of course, a fact that when we raised the point some time back of a partial mutual can- cellation of inter-Allied debts, we were far more concerned with the plight of the Allies than with our own situation. However, we have now by regu- larizing our own indebtedness to the United States earned some right to look upon this further problem of the indebtedness of our Allies in a large and impartial fashion. Having undertaken at considerable strain to the taxpayer to meet to the last penny our own indebted- ness to America, there must, of necessity, be a limit to the generosity which we are able to extend to our debtors. The two principal debtors, as shown in the figures already given, are France and Italy, and, to take the case of those two countries, it is not difficult to see how our own action, and, the action of our debtors, must be governed, to a large extent, by the attitude of America. To revert to the homely illustration I have already given : it may be possible for John Smith and Jonathan Fletcher to agree upon a common course of action with regard to Monsieur A's indebtedness, but neither the one nor the other can very well act independently. To do so would mean that not only Monsieur A but the exacting creditor would benefit at the expense of the lenient creditor. I would like it to be clearly understood that I am not suggesting that the claim of the United States upon our Allies may not be just as equitable as the claim upon this country, to which we have responded. I have only endeavoured to show how, in the case of countries more stricken by the War than Great Britain, the whole question of Reparation payments (which in their turn are linked with inter-Allied debts) and War debts is affected at every turn by the fact of the United States being the chief creditor. Yet, until this financial tangle is straightened. out, there can be no return either of political peace or of International security and prosperity. —I am, Sir, yours faithfully,

Previous page

Previous page