NELSON'S HOT POTATO

Samantha Weinberg on

the threat of prosecution facing Winnie Mandela

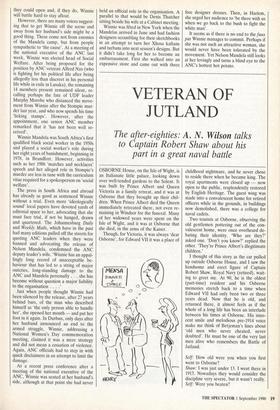

Johannesburg AS IF more than 500 deaths in the unrest since the ANC formally renounced the armed struggle were not enough of a headache for Nelson Mandela, he may soon have to face up to an even more distressing problem — the possible immi- nent prosecution of his wife Winnie.

The Attorney-General Klaus von Lieres is also presumably losing sleep over whether to bow to the weight of evidence pointing to Winnie's role in the assault and subsequent murder of the teenage activist Stompie Seipei in December 1988 — quite apart from other alleged violent crimes and bring criminal charges against the wife of the man whom many South Africans regard as the country's only hope for salvation.

The matter has now gone too far, the allegations too oft repeated and too serious to be ignored. But Von Lieres finds himself in a most uncomfortable position: of being damned if he goes ahead and instigates criminal charges against Winnie, and damned if he doesn't. He has promised to make up his mind in the next week or two.

If her prosecution goes ahead, Winnie would be given a chance to defend herself — Mandela himself has bemoaned her lack of opportunity to do so — but if she is found guilty and sentenced to a period of imprisonment, it would defile the peace process at a critical time.

Mandela has chosen to follow to the letter the words of the marriage service and stand by his wife for better or for worse, and by doing so, has staked his own credibility on the outcome. Friends of the family say he is abiding by an ancient tradition of the Xhosa (his own tribe) which says a husband must take responsi- bility for his wife's actions. In any case all the visible evidence is that he is devoted to her. Thus if Winnie were to be found guilty — which is by no means beyond the realms of possibility — his name would be dragged through the mud along with hers, with all that would entail.

If the decision is taken not to try her, then the credibility of the whole legal system (already minimal) would be dimi- nished. Whatever the real reasons, it would inevitably be seen as a political decision and one which would provoke a storm of criticism across the spectrum of political colour.

Two weeks ago Jerry Richardson, the `coach' of the so-called Mandela Football Team — a gang of brutish thugs who acted as Winnie Mandela's unofficial bodyguards while her husband was in detention — was sentenced to death and 18 years' imprison- ment for crimes including the murder of 14-year-old Stompie. During his summing- up, Mr Justice B. 0. Donovan accepted the eye-witness evidence that Winnie was present — and took an active part — in the beating up of Stompie.

In an interview with a local paper, one of the youths present at the time described Winnie as 'wild' and having 'savage eyes as she turned back to punching me . . . Mrs Mandela then stood back and watched with a satisfied look on her face. I was shocked that this woman — the mother of the nation — could do this.'

In pleading mitigation, the defence counsel tried to claim that Richardson's sanity had been affected by his idolisation of Winnie, whom he saw as a 'source of self-worth' and depended upon to the extent of calling her 'mammy'.

Winnie has also been implicated in a number of other alleged crimes carried out by members of the football club, but never been charged. It is almost as though she had been given a temporary moratorium while her husband was in jail, but now he is out, the flood gates of accusation look as if they could open and, if they do, Winnie will battle hard to stay afloat.

However, there are many voices suggest- ing that to get Winnie off the scene and away from her husband's side might be a good thing. These come not from enemies of the Mandela camp, but from people sympathetic to 'the cause'. At a meeting of the national executive of the ANC last week, Winnie was elected head of Social Welfare. After being proposed for the position by ANC veteran Alfred Nzo (who is fighting for his political life after being allegedly less than discreet in his personal life while in exile in Lusaka), the remaining 14 members present remained silent, re- calling perhaps the fate of UDF leader Murphy Morobe who distanced the move- ment from Winnie after the Stompie mur- der last year, and who now spends his time 'licking stamps'. However, after the appointment, one senior ANC member remarked that it 'has not been well re- ceived'.

Winnie Mandela was South Africa's first qualified black social worker in the 1950s and played a social worker's role during her eight years of banishment, beginning in 1978, in Brandfort. However, activities such as her 1986 'matches and necklaces' speech and her alleged role in Stompie's murder are less in tune with the curriculum vitae required for a spokesperson on 'social welfare'.

The press in South Africa and abroad has already as good as sentenced Winnie without a trial. Even more 'ideologically sound' local papers have devoted yards of editorial space to her, advocating that she must face trial, if not be hanged, drawn and quartered. The Johannesburg Daily and Weekly Mails, which have in the past had many editions pulled off the streets for quoting ANC leaders when they were banned and advocating the release of Nelson Mandela, condemned the ANC deputy leader's wife. 'Winnie has an appal- lingly long record of unacceptable be- haviour that has led to a string of major outcries, long-standing damage to the ANC and Mandela personally . . . she has become without question a major liability to the organisation . . .

Just when people thought Winnie had been silenced by the release, after 27 years behind bars, of the man who described himself as 'the only person able to handle her', she opened her mouth — and put her foot in it again. In Durban, only days after her husband announced an end to the armed struggle, Winnie, addressing a National Women's Day commemoration meeting, claimed it was a mere strategy and did not mean a cessation of violence. Again, ANC officials had to step in with quick disclaimers in an attempt to limit the damage.

At a recent press conference after a meeting of the national executive of the ANC, Winnie was seated at her husband's side, although at that point she had never held an official role in the organisation. A parallel to that would be Denis Thatcher sitting beside his wife at a Cabinet meeting.

Winnie was feted in New York when the Mandelas arrived in June and had fashion designers scrambling for their sketchbooks in an attempt to turn her Xhosa kaftans and turbans into next season's designs. But it didn't take long for her to become an embarrassment. First she walked into an expensive store and came out with three free designer dresses. Then, in Harlem, she urged her audience to 'be there with us when we go back to the bush to fight the white man'.

It seems as if there is no end to the faux pas Winnie manages to commit. Perhaps if she was not such an attractive woman, she would never have been tolerated by the movement. Yet Nelson Mandela still looks at her lovingly and turns a blind eye to the ANC's hottest hot potato.

Previous page

Previous page