VETERAN OF JUTLAND

to Captain Robert Shaw about his part in a great naval battle

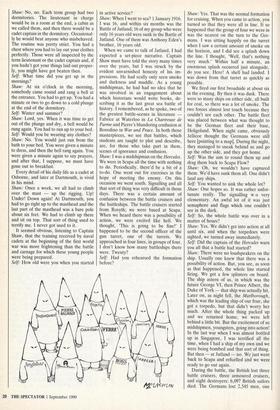

OSBORNE House, on the Isle of Wight, is an Italianate little palace, looking down over well-tended gardens to the Solent. It was built by Prince Albert and Queen Victoria as a family retreat, and it was at Osborne that they brought up their chil- dren. When Prince Albert died the Queen immediately retreated there, not even re- maining in Windsor for the funeral. Many of her widowed years were spent on the Isle of Wight, and it was at Osborne that she died, in the arms of the Kaiser.

Though, for Victoria, it was always 'dear Osborne', for Edward VII it was a place of childhood nightmare, and he never chose to reside there when he became king. The royal apartments were closed up — now open to the public, resplendently restored by English Heritage. The guest wing was made into a convalescent home for retired officers while in the grounds, in buildings now demolished, there was a college for naval cadets.

Two tourists at Osborne, observing the old gentlemen pottering out of the con- valescent home, were once overheard de- bating their identity. 'Who are they?' asked one. 'Don't you know?' replied the other. 'They're Prince Albert's illegitimate children.'

I thought of this story as the car pulled up outside Osborne House, and I saw the handsome and erect figure of Captain Robert Shaw, Royal Navy (retired), wait- ing to greet me. At 90, he is the oldest (part-time) resident and his Osborne memories stretch back to a time when Edward VII had only been two or three years dead. Now that he is old, and returned there, it almost feels as if the whole of a long life has been an interlude between his times at Osborne. His inno- cent smile and melodious pre-1914 voice make me think of Betjeman's lines about 'old men who never cheated, never doubted'. He must be one of the very last men alive who remembers the Battle of Jutland.

Self: 'How old were you when you first went to Osborne?

Shaw: I was just under 13. I went there in 1913. Nowadays they would consider the discipline very severe, but it wasn't really. Self: Were you beaten? Shaw: No, no. Each term group had two dormitories. The lieutenant in charge would be in a room at the end, a cabin as we called them, and then there would be a cadet captain in the dormitory. Occasional- ly he would beat anyone who misbehaved. The routine was pretty strict. You had a chest where you had to lay out your clothes perfectly. Those were all inspected by the term lieutenant or the cadet captain and, if you hadn't got your things laid out proper- ly, you might have got beaten then. Self: What time did you get up in the mornings?

Shaw: At six o'clock in the morning, somebody came round and rang a bell at the entrance. You had to get up. You had a minute or two to go down to a cold plunge at the end of the dormitory.

Self: Winter and summer?

Shaw: Lord, yes. When it was time to get out of the plunge and dry, a bell would be rung again. You had to run up to your bed. Self: Would you be wearing any clothes? Shaw: No. You would just run from the bath to your bed. You were given a minute to dress, and then the bell rang again. You were given a minute again to say prayers, and after that, I suppose, we must have gone out to breakfast.

Every detail of his daily life as a cadet at Osborne, and later at Dartmouth, is vivid in his mind.

Shaw: Once a week, we all had to climb over the mast — up the rigging. Up! Under! Down again! At Dartmouth, you had to go right up to the masthead and the last part of the masthead was a bare pole about six feet. We had to climb up there and sit on top. That sort of thing used to terrify me. I never got used to it.

It seemed obvious, listening to Captain Shaw, that the training received by naval cadets at the beginning of the first world war was more frightening than the battle and carnage for which these young people were being prepared.

Self: How old were you when you started in active service?

Shaw: When I went to sea? 1 January 1916. I was 16, and within six months was the Battle of Jutland; 16 of my group who were only 16 years old were sunk in the Battle of Jutland. One of them was Anthony Eden's brother, 16 years old.

When we came to talk of Jutland, I had expected a set-piece narrative. Captain Shaw must have told the story many times over the years, but I was struck by the evident unvarnished honesty of his im- pressions. He had really only seen smoke and darkness and muddle. As a young midshipman, he had had no idea that he was involved in an engagement about which historians would write books, de- scribing it as the last great sea battle of history. I remembered, as he spoke, two of the greatest battle-scenes in literature — Fabrice at Waterloo in La Chartreuse de Parme and Pierre's blundering confusion at Borodino in War and Peace. In both those masterpieces, we see that battles, which students are taught to plot and describe, are, for those who take part in them, scenes of ignorance and confusion.

Shaw: I was a midshipman on the Hercules. We were in Scapa all the time with nothing to do. Periodically, there'd be a bit of a to-do. One went out for exercises in the hope of meeting the enemy. On this occasion we went south. Signalling and all that sort of thing was very difficult in those days. There was a certain amount of confusion between the battle cruisers and the battleships. The battle cruisers started from Rosyth; we were based at Scapa.

When we heard there was a possibility of action, we were excited like hell. We thought, 'This is going to be fine!' I happened to be the second officer of the gun turret, one of the turrets. We approached in four lines, in groups of four. I don't know how many battleships there were. Twenty?

Self: Had you rehearsed the formation before? Shaw: Yes. That was the normal forthation for cruising. When you came to action, you turned so that they were all in line. It so happened that the group of four we were in was the nearest on the turn to the Ger- mans. I was sitting happily on the turret when I saw a certain amount of smoke on the horizon, and I did see a splash down the line. I thought, 'Well, that's nothing very much.' Within half a minute, an enormous splash occurred just alongside, do you see. Here! A shell had landed. I was down from that turret as quickly as possible.

We fired our first broadside at about six in the evening. By then it was dusk. There were so many ships on either side, all built for coal, so there was a lot of smoke. The two forces almost lost touch because they couldn't see each other. The battle fleet was placed between what was thought to be the German fleet and their base, Heligoland. When night came, obviously Jellicoe thought the Germans were still here [pointing to a map]. During the night, they managed to sneak behind us and go up the other side, and they got home. Self: Was the aim to round them up and drag them back to Scapa Flow?

Shaw: Oh, we wouldn't have captured them. We'd have sunk them all. One didn't land any ships.

Self: You wanted to sink the whole lot? Shaw: One hopes so. It was rather unfor- tunate really. The signalling w is very elementary. An awful lot of it was just semaphore and flags which one couldn't see in the dark.

Self: So, the whole battle was over in a matter of hours?

Shaw: Yes. We didn't get into action at all until six, and when the torpedoes were sighted, we turned away immediately. Self: Did the captain of the Hercules warn you all that a battle had started?

Shaw: There were no loudspeakers on the ship. Usually one knew that there was a possibility of action. But, you see, as soon as that happened, the whole line started firing. We got a few splinters on board. The ship astern of us, in which was the future George VI, then Prince Albert, the Duke of York — that ship was actually hit. Later on, as night fell, the Marlborough, which was the leading ship of our four, she got a torpedo, but that didn't worry her much. After the whole thing packed up and we returned home, we were left behind a little bit. But the excitement of us midshipmen, youngsters, going into action!

In the last war when I was almost bottled up in Singapore, I was terrified all the time, when I had a ship of my own and we were being bombed and that sort of thing. But then — at Jutland -- no. We just went back to Scapa and refuelled and we were ready to go out again.

During the battle, the British lost three battle cruisers, three armoured cruisers, and eight destroyers: 6,097 British sailors died. The Germans ,lost 2,545 men, one battleship, one battle cruiser, four light cruisers and five destroyers.

Jutland was not publicised in England at all. Not even the men who had fought in the battle that night were aware of the casualties, the loss of ships, or of the escape of the German fleet.

Shaw: That all came from Germany. They announced that they had had a big victory. It was the first anyone had heard about it in England.

The next time Shaw saw the German fleet was after the Armistice had been signed in 1918. By then, he was a sub- lieutenant. The German fleet had been captured, and taken to Rosyth.

Shaw: A few weeks later, they were all sent north to Scapa Flow, with a squadron of our ships to keep guard on them. The Allied politicians couldn't agree on what was to become of them. Scapa is pretty bleak even in summer, so it wasn't a popular assignment. I was one of the few who was there when the Germans scuttled their fleet. They chose a day when the squadron was at sea on exercises. I was left behind, in charge of a patrol trawler. Suddenly we noticed that the Germans were leaving their ships. By the time we got near them, the ships were visibly sinking, and one of those big battleships turned turtle just as we were about to come alongside. Of course, the Germans got the better of us in a sense, since we were supposed to be making sure no harm came to their ships; but I don't think we minded too much. Seeing the anchorage with all those big ships just keeling over and going down, our main feeling was relief.

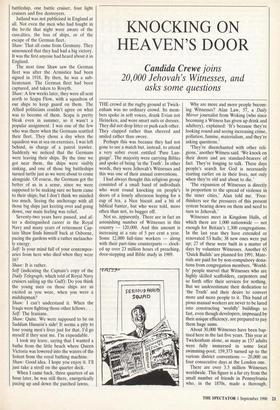

Seventy-two years have passed, and af- ter a distinguished career in the Royal Navy and many years of retirement Cap- tain Shaw finds himself back at Osborne, pacing the gardens with a rather melancho- ly energy.

Self: Is your mind full of your contempor- aries from here who died when they were 16?

Shaw: It is rather.

Self (indicating the Captain's copy of the Daily Telegraph, which told of Royal Navy cruisers sailing up the Gulf): Do you think the young men on those ships are as excited as you were, when you were a midshipman?

Shaw: I can't understand it. When the Iraqis were fighting those other fellows . . . Self: The Iranians.

Shaw: Quite. We were supposed to be on Saddam Hussein's side! It seems a pity to lose young men's lives just for that. I'd go myself if they sent me. I'm expendable.

I took my leave, saying that I wanted a bathe from the little beach where Queen Victoria was lowered into the waters of the Solent from the royal bathing machine. Shaw: Good idea. I hope you enjoy it. I'll just take a stroll on the quarter deck.

When I came back, three quarters of an hour later, he was still there, energetically pacing up and down the parched lawns.

Previous page

Previous page