ARTS

Museums

Islamic artistry

Patricia Jellicoe

The al-Sabah Collection (Kuwait National Museum)

Alate as 1963, in Ernst Kuhnel's survey Islamic Arts, its publishers noted that 'Islamic art is still a largely unfamiliar field to the collector and has attracted fewer connoisseurs than Oriental work'. This situation has changed considerably since then due to trade, travel and political upheavals. There are still some, however, who may not realise that interest in Islamic art is not exclusively Arab, for many eminent Jewish scholars have contributed to its studies. There are others who do not realise that but for early Arabic transla- tions Greek and Hellenistic knowledge of medicine, mathematics and sciences would have been irrevocably lost to us.

Saddam Hussein's posturing as an Arab patriot, manipulating the understandable reactions of the present generation in the Muslim world to the unhappy political results of the first world war, is taking a tragic and terrible path. In contrast, the Arabs' deeply felt aspirations towards a recognition of the ancient heritage of Islam have been embodied in the vision of Sheikh Nasser al-Ahmed al-Sabah and his wife, Sheikha Hussa, with their creation of the Museum of Islamic Art in Kuwait's National Museum. Their combination of love for and pride in their own artistic and historic traditions, together with complete generosity of mind, time and money, has in remarkably few years collected and re- turned to their homeland some of the most splendid examples of every aspect of Isla- mic art and knowledge, with the aim of allowing those living in Kuwait to see the products of their great civilisation of the past. Their hope was that 'the unique beauty of the arts of the Muslims would be better understood by fellow Muslims and by the Western world'.

Kuwait became a nation only after the first world war, and its oil wealth only its own after 1975, when the Sheikh began to collect Islamic art. The Museum opened on 25 February 1983 — Kuwait's National Day — with 20,000 objects covering a period of some 1,300 years and extending over Syria, Persia, Iraq, Egypt, Turkey, Morocco and India, as well as other Muslim Arab countries. With Sheikha Hussa as its director, the Museum has become deservedly renowned.

Art in Islam has always depended upon

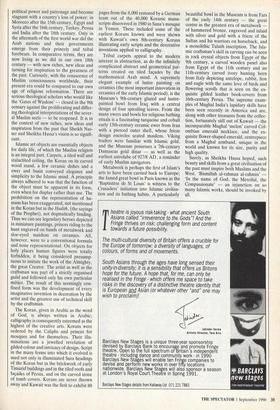

Bronze bowl, engraved and inlaid with silver and gold, front Furs, Iran, 14th century political power and patronage and become stagnant with a country's loss of power: in Morocco after the 15th century, Egypt and Syria after the 16th century, Turkey, Persia and India after the 18th century. Only in the aftermath of the first world war did the Arab nations and their governments emerge from their princely and tribal forebears. In comparative terms, they are now living as we did in our own 18th century — with new riches, new ideas and turning for inspiration to the greatness of the past. Curiously, with the renascence of Muslim consciousness worldwide, their present era could be compared to our own age of religious reformation. There are serious theological scholars who would like the 'Gates of Wisdom' — closed in the 9th century against the proliferating and differ- ing theological interpretations of the sever- al Muslim sects — to be reopened. It is in the context of new riches, new ideas and inspiration from the past that Sheikh Nas- ser and Sheikha Hussa's vision is so signifi- cant.

Islamic art objects are essentially objects for daily life, of which the Muslim religion is an integral part. Carpets, a tiled wall and stalactited ceiling, the Koran on its carved wood stand, a few ceramic dishes and a ewer and basin conveyed elegance and simplicity to the Islamic mind. A principle always adhered to was that the function of the object must be apparent in its form, even when for display rather than use. The prohibition on the representation of hu- mans has been exaggerated, not mentioned in the Koran but in the Hadith, (the sayings of the Prophet), not dogmatically binding. Thus we can see legendary heroes depicted in miniature paintings, princes riding to the hunt engraved on bands of metalwork and sloe-eyed maidens on ceramics. All, however, were to a conventional formula and none representational. On objects for holy places human figures were totally forbidden, it being considered presump- tuous to imitate the work of the Almighty, the great Creator. The artist as well as the craftsman was part of a strictly organised guild and followed only his own particular métier. The result of this seemingly con- fined form was the development of every imaginative invention in decoration by the artist and the greatest use of technical skill by the craftsman.

The Koran, given in Arabic as the word of God, is always written in Arabic; calligraphy is consequently esteemed as the highest of the creative arts. Korans were ordered by the Caliphs and princes for mosques and for themselves. Their illu- minations are a jewelled revelation of gilded colour and intricacy of design. Script in the many forms into which it evolved is used not only in illuminated Sura headings of the Koran but in the brickwork of early Timurid buildings and in the tiled roofs and façades of Persia, and on the carved stone of tomb covers. Korans are never thrown away and Kuwait was the first to exhibit 80 pages from the 8,000 restored by a German team out of the 40,000 Koranic manu- scripts discovered in 1980 in Sana's mosque in Yemen. These included some of the earliest Korans known and were shown with Kuwait's own 8th-century Korans illustrating early scripts and the decorative inventions applied to calligraphy.

Tribal carpets appeal to the modern interest in abstraction, as do the infinitely complicated abstract and geometrical pat- terns created on tiled façades by the mathematical Arab mind. A supremely elegant example of lustre painting on ceramics (the most important innovation in ceramics of the early Islamic period), is the Museum's 9th-century glazed and lustre- painted bowl from Iraq with a central design of four spiralling leaves. From the many ewers and bowls for religious bathing rituals is a fascinating turquoise and cobalt early 13th-century ceramic ewer from Iran with a pierced outer shell, whose frieze design encircles seated maidens. Viking traders were familiar with Islamic gold, and the Museum possesses a 7th-century Damascus gold dinar — as well as the earliest astrolabe of 927/8 AD, a reminder of early Muslim navigators.

Metalwork is perhaps the first of Islam's arts to have been carried back to Europe; the famed great bowl in Paris known as the 13aptistere de St Louis' is witness to the Crusaders' initiation into Islamic civilisa- tion and its bathing habits. A particularly beautiful bowl in the Museum is from Fars of the early 14th century — the great centre in the greatest era of metalwork of hammered bronze, engraved and inlaid with silver and gold with a frieze of the Sultan and his warriors on horseback, and a monolithic Tuluth inscription. The Isla- mic craftsman's skill in carving can be seen in rock crystal objects from Egypt of the 9th century, a carved wooden panel also from Egypt of the 11th century and an 11th-century carved ivory hunting horn from Italy depicting antelope, rabbit, lion and eagle with the same love of birds and flowering scrolls that is seen on the ex- quisite gilded leather book-covers from 16th-century Persia. The supreme exam- ples of Mughal India's lapidary skills have been seen recently in America and are, along with other treasures from the collec- tion, fortunately still out of Kuwait — the incomparable Mughal 'melon' carved Col- ombian emerald necklace, and the ex- quisite flower-shaped emerald, centrepiece from a Mughal armband, unique in the world and known for its size, purity and high quality.

Surely, as Sheikha Hussa hoped, such beauty and skills from a great civilisation of the past must inspire both Muslims and the West. 'Bismillah al-rahman al-rahmin' 'In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate' — an injunction on so many Islamic works, should be invoked by all.

Previous page

Previous page