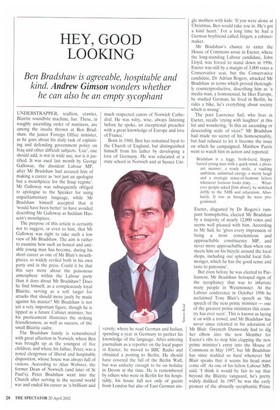

HEY, GOOD LOOKING

Ben Bradshaw is agreeable, hospitable and

kind. Andrew Gimson wonders whether

he can also be an empty sycophant

UNDERSTRAPPER, scullion, crawler, Blairite soundbite machine, liar. These, in roughly ascending order of nastiness, are among the insults thrown at Ben Bradshaw, the junior Foreign Office minister, as he goes about his daily task of explain ing and defending government policy on Iraq and other difficult subjects. 'Liar', one should add, is not in wide use, nor is it justified. It was used last month by George Galloway, the dissident Labour MP, after Mr Bradshaw had accused him of making a career as 'not just an apologist but a mouthpiece for the Iraqi regime'. Mr Galloway was subsequently obliged to apologise to the Speaker for using unparliamentary language, while Mr Bradshaw himself accepted that it 'would have been better' to have avoided describing Mr Galloway as Saddam Hussein's mouthpiece.

The purpose of this article is certainly not to suggest, or even to hint, that Mr Galloway was right to take such a low view of Mr Bradshaw. The aim is rather to examine how such an honest and amiable young man has become, during his short career as one of Mr Blair's mouthpieces, so widely reviled both in his own party and in the press. Could it be that this says more about the poisonous atmosphere within the Labour party than it does about Mr Bradshaw? Does he find himself, as a conspicuously loyal Blairite, serving as a soft target for attacks that should more justly be made against his master? Mr Bradshaw is not yet a very important figure, though he is tipped as a future Cabinet minister, but his predicament illustrates the striking friendlessness, as well as success, of the small Blairite cadre.

The Bradshaw family is remembered with great affection in Norwich, where Ben was brought up as the youngest of five children, and where his father, Peter, was a noted clergyman of liberal and hospitable disposition, whose house was always full of visitors. According to Alan Webster, the former Dean of Norwich (and later of St Paul's), Peter Bradshaw went into the Church after serving in the second world war and ended his career as 'a brilliant and much respected canon of Norwich Cathedral. He was witty, wise, always listening before he spoke, an exceptional preacher with a great knowledge of Europe and love of France.'

Born in 1960, Ben has remained loyal to the Church of England, but distinguished himself from his father by developing a love of Germany. He was educated at a state school in Norwich and at Sussex Uni versity, where he read German and Italian, spending a year in Germany to perfect his knowledge of the language. After entering journalism as a reporter on the local paper in Exeter, he moved to BBC Radio and obtained a posting to Berlin. He should have covered the fall of the Berlin Wall, but was unlucky enough to be on holiday in Devon at the time. He is remembered by others who were in Berlin for his hospitality, his house full not only of guests from London but also of East German sin gle mothers with kids: 'If you were alone at Christmas, Ben would take you in. He's got a kind heart.' For a long time he had a German boyfriend called Jurgen, a cabinetmaker.

Mr Bradshaw's chance to enter the House of Commons arose in Exeter, where the long-standing Labour candidate, John Lloyd, was forced to stand down in 1996. Exeter was still by a margin of 3,000 votes a Conservative seat, but the Conservative candidate, Dr Adrian Rogers, attacked Mr Bradshaw in terms which proved thoroughly counterproductive, describing him as 'a media man, a homosexual, he likes Europe, he studied German, he lived in Berlin, he rides a bike, he's everything about society which is wrong'.

The poet Lawrence Sail, who lives in Exeter, recalls 'crying with laughter' at this list and wondering, 'Is this an ascending or descending scale of vices?' Mr Bradshaw had made no secret of his homosexuality, but had refused to let it become the issue on which he campaigned. Matthew Parris went to watch him in action and reported:

Bradshaw is a leggy, fresh-faced, floppy.

haired young man with a quick mind, a pleasant manner, a ready smile, a vaulting ambition, unlimited energy, a merry laugh and a strategic sense-of-humour failure whenever humour looks risky... . Whatever people asked [him about], he switched deftly to the NHS and education. Absolutely. It was as though he were programmed.

Exeter, disgusted by Dr Rogers's rampant homophobia, elected Mr Bradshaw by a majority of nearly 12,000 votes and seems well pleased with him. According to Mr Sail, he 'gives every impression of being a most conscientious and approachable constituency MP, and never more approachable than when one meets him on his bicycle around the local shops, including our splendid local fishmonger, which he has the good sense and taste to patronise'.

But even before he was elected to Par liament, Mr Bradshaw betrayed signs of the sycophancy that was to infuriate many people in Westminster. At the Labour conference in October 1996 he acclaimed Tony Blair's speech as 'the speech of the next prime minister — one of the greatest prime ministers this coun try has ever seen'. This is known as laying it on with a trowel, and Mr Bradshaw has never since relented in his adoration of Mr Blair. Gwyneth Dunwoody had to dig her elbow into the new Member for Exeter's ribs to stop him clapping the new prime minister's entry into the House of Commons in May 1997, but Mr Bradshaw has since nodded so hard whenever Mr Blair speaks that it seems his head must come off. As one of his fellow Labour MPs said, 'I think it would be fair to say that beyond the Blairite vanguard, he's pretty widely disliked. In 1997 he was the early pioneer of the absurdly sycophantic Prime Minister's question. Only someone with no sense of irony could have done that.' During the Kosovo campaign, he established himself as a backbench cheerleader for the hawkish government line.

For all his success — he has, after all, won preferment, and is now very often seen on our television screens, doing his best to promote the government line on Iraq or Israel — Mr Bradshaw cuts an isolated figure at Westminster. He suffers the fate of teacher's pet, mocked and envied by his yobbish classmates. The laddish culture that persists among Labour backbenchers is not for him, nor does his sincere, evangelical manner go down well with lobby journalists. To them it seems smarmy arid naive. Westminster can still be a rough and masculine place, repugnant to those who wince rather than laugh at cynical jokes, which includes a high proportion of Labour's female MPs. So it is no surprise that in the words of one male observer. 'Bradshaw is very good with the Labour women. He likes these ugly women who are useless MPs.' Women say that he also comes across well to them on television. He is very good-looking, and speaks with a becoming seriousness.

Like his hero Mr Blair, Mr Bradshaw has risen without having worked his way up through the trades unions or local government. Both men are from middle-class backgrounds where there was not much money around. Both of them know how to deploy niceness as a political weapon (and perhaps Mr Bradshaw's apparent sycophancy is just his idea of niceness). Both, to some people, sound bogus, but to many others seem pleasantly unpolitical. It is easy to imagine either of them joining the Conservative party, if that had been a more modern, liberal thing to do than it was in 1975, when Mr Blair joined the Labour party in Chelsea, or in 1984, when Mr Bradshaw joined it in Exeter. As one Tory commentator said of Mr Bradshaw, 'He's the sort of careerist who should have joined the Tory party. The Tories used to be riddled with ideologically empty people like Bradshaw.' Mr Bradshaw (accompanied by his long-term partner Neal Dalgleish in a kilt) and Peter Mandelson were among the Labour guests at Shaun Woodward's opulent 40th birthday party, which took place in October 1998, shortly before Mr Woodward, another man who might have joined either party, crossed the floor of the House of Commons from the Conservative to the Labour side.

Mr Bradshaw's career with the BBC, which continued after his return from Berlin on programmes such as the World At One, gave him an excellent reason for not getting too closely involved in party politics until he won the nomination at Exeter. A Labour insider who has seen much of him said, 'He has no Labour politics. He has no background in the party. He's not part of any regional network. He's not one of the hard-core modernisers who were there in 1994 [when Mr Blair became leader]. He's pretty much of a loner.' Mr Bradshaw's decision to attach himself so firmly to the Blairites, though doubtless in accordance with his feelings, may also spring partly from a sense of his own isolation. His prospects in a Labour party led by Gordon Brown would be questionable.

Mr Bradshaw has much closer links with two of the other institutions that have done much to form this country's idea of itself: the Church of England and the BBC. Although both contain large numbers of people who can be described as left-wing, both sec it as their mission to speak to the whole nation, in a way that the traditional Labour party seldom wanted to do. In aspiration, at least, they are 'big tent' organisations, and are therefore natural allies or training grounds for a group such as New Labour, which aspires to become the natural party of government.

It is not, by the way, quite fair to describe Mr Bradshaw as ideologically empty. He travels light on his bicycle, but thinks of himself as a man with a passionate commitment to Europe. In October 1997 he began a newspaper article with the words, 'At last we have a government that knows where it's going with the euro', and predicted entry in '2002 or 2003'. He is a keen attender at the Konigswinter conferences which bring influential Britons and Germans together for off-the-record discussions, and where he can invariably be found supporting whatever is the received wisdom among those members of the British and German ruling classes who have a passionate commitment to Europe, which at these particular conferences, valuable though they are, means about 98 per cent of the participants.

'I really think you should be a bit nicer to him,' one woman said after reading this article. 'I think he's fundamentally a nice guy.' She is probably right. Mr Bradshaw's worst fault may be his lack of the hypocrisy by which ambitious Englishmen have long sought to hide their craving for office.

Previous page

Previous page