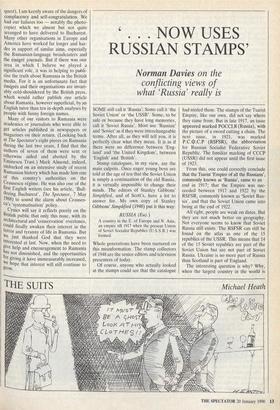

. . NOW USES RUSSIAN STAMPS'

Norman Davies on the

conflicting views of what 'Russia' really is

SOME still call it 'Russia'. Some call it 'the Soviet Union' or `the USSR'. Some, to be safe or because they have long memories, call it 'Soviet Russia'. Most use 'Russian' and 'Soviet' as if they were interchangeable terms, After all, as they will tell you, it is perfectly clear what they mean. It is as if there were no difference between `Eng- land' and `the United Kingdom', between `English' and 'British'.

Stamp catalogues, in my view, are the main culprits. Once eager young boys are told at the age of ten that the Soviet Union is simply a continuation of the old Russia, it is virtually impossible to change their minds. The editors of Stanley Gibbons' Simplified, and of Scott's, have a lot to answer for. My own copy of Stanley Gibbons' Simplified (1948) put it this way: RUSSIA (Eu).) A country in the E. of Europe and N. Asia, an empire till 1917 when the present Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) was formed.

Whole generations have been nurtured on this misinformation. The stamp collectors of 1948 are the senior editors and television presenters of today.

Of course, anyone who actually looked at the stamps could see that the catalogue had misled them. The stamps of the Tsarist Empire, like our own, did not say where they came from. But in late 1917, an issue appeared marked POCCI 51 (Russia), with the picture of a sword cutting a chain. The next issue, in 1921, was marked (RSFSR), the abbreviation for Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. The familiar marking of CCCP (USSR) did not appear until the first issue of 1923.

From this, one could correctly conclude that the Tsarist 'Empire of all the Russians', commonly known as 'Russia', came to an end in 1917; that the Empire was suc- ceeded between 1917 and 1922 by the RSFSR, commonly known as 'Soviet Rus- sia', and that the Soviet Union came into being at the end of 1922.

All right, people are weak on dates. But they are not much better on geography. Not everyone seems to know that Soviet Russia still exists. The RSFSR can still be found on the atlas as one of the 15 republics of the USSR. This means that 14 of the 15 Soviet republics are part of the Soviet Union but are not part of Soviet Russia. Ukraine is no more part of Russia than Scotland is part of England.

The interesting question is why? Why, when the largest country in the world is

under discussion, do so many otherwise well-informed people get it wrong? Why do distinguished professors persist in teaching courses entitled 'Russian History from 1917 to the Present'? Why does the splendid Times Atlas of the Second World War tell us that on 22 June 1941 the Wehrmacht crossed the `German/Russian frontier'? Why does David Dimbleby tell us on Panorama, once again, that '20 million Russians' were killed during the war? There must be more to it than just the name.

One reason, perhaps, is sheer com- placency. 19th-century habits die hard.

More recently, one has been faced with the well-intentioned but wrong-headed de- sire to give 'equivalence' to the superpow- ers. 'America' has to be balanced with `Russia', the USA with the USSR, the 'Americans' with 'the Russians', the evil empire with the evil empire. Lithuania must be rather like Louisiana only more so.

There are linguistic objections, too. Some specialists jib at talking about 'the Soviets', since the term can be ambiguous. So they go on talking about 'the Russians' — which is usually completely wrong.

At root, the matter turns on two oppo- site and incompatible views about what `Russia' really is. The traditional view, blessed by the Russian Orthodox Church across the centuries, maintains that 'Holy Russia, one and indivisible' is a natural and cohesive entity, whose heroic leaders are called by God and destiny to rule indef- initely over the lesser breeds. It is an East European version of the White Man's Burden. It also assumes that the Soviet Union is just an updated version of the Tsarist Empire, different in name and political colouring but not in substance. The opposite view maintains that 'Russia' in the traditional sense is a convenient political fiction which hides a rag-bag of imperial conquests and captive nations, who have little common culture or interest. Its proponents would argue that 'Russia' can only be properly applied nowadays to the homeland of the Russians in the RSFSR: that the Russian nation is just one among many in the USSR: and that Russia has no more right to rule over the 14 non-Russian republics than England had a right to rule over Ireland or India. The latter view is widely held among that half of the Soviet population who are not Russians, and was briefly coutred in the 1920s by some of the Marxist international- ists. The former, traditional view is held by Russian nationalists, by Stalinists, and by Enoch Powell. For obvious reasons, it is not widely contested by all those Western sovietologists who have been raised during the last 60 years on a diet of Russocentrism and official Soviet sources.

The Stalinist theses, clearly set out in the teaching decrees of 1934, reclothed the old assumptions in Marxist jargon, but re- tained the essentials Among other things, they support three main contentions: — That the Great Russian Nation enjoys a leading role among the nationalities of the USSR, parallel to the leading role of the Communist Party among all political forces.

— That the Soviet Union grew out of the former Russian Empire through a process of natural evolution, inspired by the vic- tory of the proletariat in the class struggle and hindered only by the nefarious work of reactionaries.

— That all the non-Russian nationalities joined the great Soviet family by joyful and spontaneous acts of voluntary choice. Opponents of the union (which have to exist for dialectical reasons) could only be found in the ranks of bourgeois national- ists, class enemies, traitors, and other `degenerates'.

To this end, it was absolutely vital to suppress any full description of the events which occurred between the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 and the creation of the USSR in 1922/3. In particular, one had to skate over the fact that all the non- Russian nations of the former Empire chose to form independent national states of their own in 1917-22, and that every single one of them was then invaded and conquered by the Red Army. The USSR could only have been created by adding the newly defeated republics to the existing territory of the RSFSR. Independent Ukraine, or independent Georgia which opted for the Mensheviks in preference to the Bolsheviks, could only be mentioned to be denigrated.

Similarly, in describing the conflicts of 1917-22, the Stalinists prefer the mislead- ing label of the 'Russian Civil War'. And they insist on a simplified, dialectical analysis confined to the struggle of the `Reds' against the 'Whites'. They thereby avoid any clear presentation of the three- sided contest which took place in most parts of the former Empire, where the national republics came under attack from both the Reds and the Whites. In explain- ing the ultimate Bolshevik victory, they have to omit the basic strategic disadvan- tage of the Whites, who, being excluded from their Russian heartland by Lenin's seizure of the central government, were forced to operate in non-Russian areas, notably Ukraine, where they lacked the support of the local population.

who wa's Lenin's Commissar for the Nationalities at the time, shared the Whites' belief in a 'Russia., one and indi- visible', and proceeded to subject the defeated national republics to murderous punishments. Stalin's native Georgia was

one of the early victims. The Soviet nationalities were not 'inherited% they were seized by force.

At which point, one has to ask why the fair-minded British, whose army was sent to intervene on behalf of the 'Whites', did not really notice what was going on. One can only assume that it has something to do with their natural sympathy for fellow imperialists in trouble, or with nostalgia for our late and noble tsarist ally. The British of 1917-22 were no more disposed to appreciate 'nationalist' Georgians or Ukrainians than nationalist Irish or Indi- ans.

A similar syndrome recurred during the second world war. With Stalin in the Kremlin, and E. H. Carr in the editorial offices of the Times, and with the Soviet nationalities dallying once more with our German foe, all our thoughts about East- ern Europe were conditioned by our admiration and support for 'Russia'. We owed our skins to the Red Army, and there was precious little fellow-feeling left for the assorted East Europeans in our midst who knew better.

Now that the Stalinist bubble has burst, it is time perhaps for a little 'new thinking' of our own. It is time to realise that rejecting Stalinism involves more than the condemnation of his political methods. It calls for the cleansing of a whole stable of imperialist myths, which were co-opted into Stalin's ideology, and which were often imbibed unknowingly by Western opinion. We will have to revise not just the history books of Eastern Europe, but the constructs and vocabulary of its political geography. If one wants to understand why the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh arouses such ferocious passions after nearly 70 years, one has to remember who created it and for what purpose. If one wants to know why the Uniate Catholic religion has been forcibly suppressed in Byelorussia and Ukraine, not just by Stalin in 1946 but by every Russian tsar since the 17th century, one needs to know something of the non-Russian Orthodox traditions of those parts. (No, it wasn't the Russian Orthodox Church that was introduced to Kiev in 988.)

Fortunately, there are signs of progress. The stamp catalogues have begun to escape from the Stalinist grip. Stanley Gibbons' latest edition still insists on the title 'Russia' for a single section dealing with all issues from 1858 to the present. But there is a small note announcing 'Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: 6 July 1923'. All the national republics of the period after 1917 are correctly described as independent states. This is a great advance on the 1948 edition, where Estonia was 'a district . . on the Gulf of Finland:, Ukraine was 'a district of S.W. Russia'; and Georgia was 'formerly part of Trans- caucasian Russia . . . temporarily indepen- dent . . now part of Soviet Russia. Now uses Russian stamps.'

Previous page

Previous page