A MEMBER OF THE ESTABLISHMENT

Dominic Lawson meets

Lord Rees-Mogg, whose charm covers up his inconsistency

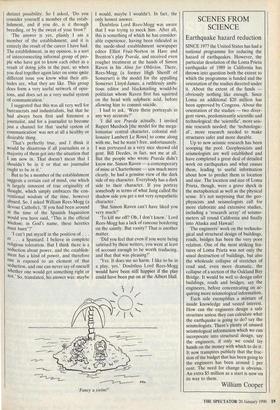

IF YOU look in through the window of the antiquarian booksellers, Pickering & Chat- to, No. 17 Pall Mall, you will see the reassuringly grey and dignified figure of its proprietor scrutinising some recently ac- quired rare first edition. It is Lord Rees- Mogg, doing what he likes most. But if you walk in and look more closely at the peer (he is too engrossed to look up) things suddenly seem less solid. The shoes are of black suede. The shirt is pink, the collar buttoned down. And the pin-striped suit that 'looked so great and good from the outside: my dear, the stripes are red! One begins to doubt the very authenticity of the incunabula. It is, of course, a clue: Lord Rees-Mogg, whose grey conservative im- age has helped to win him more sinecures, chairmanships and governorships than a man would know what to do with, has a vulgar streak, if only as wide as the thin red stripes of his two-piece suit.

In fact this would have already been apparent to anyone who had watched a 'God slot' television programme in the early 1970s, A Chance to Meet. The then Mr William Rees-Mogg, editor of the Times had confessed that he harboured the ambition to address a mass rally at the Albert Hall. Was this a sincere ambition, I asked Lord Rees-Mogg, as soon as we had sat down in the upstairs flat at 17 Pall Mall, looking directly across at the Reform Club? Yes, he replied, it was sincere.

I still was not quite satisfied. 'Did you imagine yourself addressing the sort of quiet attentive audience which attends second-rate doubles tennis matches at the Albert Hall? Or did you imagine yourself addressing the sort of crowd which attends the last night of the Proms?' More like the last night of the Proms,' replied Lord Rees-Mogg. Well, it is true that he has a deep and resonant voice, and as for that peculiar lateral lisp of his, did not Winston Churchill also suffer from squelchy s's?

In fact Rees-Mogg's leaders for the Times were often on a last night of the Proms level of tub-thumping populism, with headings such as 'A Picnic on a Volcano', or 'A Pitiless Innuendo'. 'You really were, or wanted to be, a populist,' I said to Rees-Mogg. 'Good political journalism has an ele- ment of popular appeal in it. As a techni- cian I admire the leaders in the Sun'.

'You mean, as one leader writer to another, you salute a job well done?'

'A job extremely well done: to get that amount of content into that number of words in a way which will have that degree of impact on the given audience. I think the current leaders in the Sun are superb.' (For those Spectator readers who do not seek the Sun's guidance on topical matters of the day, I quote an example of the sort of pithy leading article that so impresses Lord Rees-Mogg: `Le Corbusier said that a house is a machine for living in. Stupid git.' Not the sort of stuff that will end up between bound volumes at Pickering & Chatto, but — Lord Rees-Mogg is abSo- lutely right — memorable in its own way.) The last leader Rees-Mogg wrote, as editor of the Times, was memorable in a rather different way. It was almost 2,000 words long, the first nine of which were: 'Mrs Shirley Williams would make a good Prime Minister.' The next 1,991 words attempted to justify this claim, with asser- tions that Mrs Williams, unlike Mrs Thatcher, 'talks to the British people in their own accents', and that although Mrs Williams 'is an egalitarian . . . wants to abolish private education . . . believes in a wealth tax . . . we must take the rough with the smooth.'

I believe I discerned an embarrassed red pin-striped blush come to the Rees-Mogg cheeks when I brought up his farewell leader as the Times editor. But I ploughed on and asked, 'Wasn't this the most ex- traordinary misjudgment — particularly for a would-be populist — to think that Mrs Williams spoke in the accents of ordinary people, and not Mrs Thatcher, with her uncanny ear for popular pre- judice?'

'I don't now judge that I was getting things particularly right but the leader was written at the time of the handover of the Times [to Rupert Murdoch] and I don't think I was anything other than particularly tired at that time.' (Mr Murdoch's com- ment on the leader, as recounted by Harold Evans in Good Times, Bad Times, was more Sun-leaderish: 'Did you see what that shit Rees-Mogg has done?') How much more angry would the new proprietor of the Times have been if he had known Rees-Mogg's most deeply hidden motives which, if I understand him correct- ly, included a wish to repay a 30-year-old favour to Shirley Williams: 'In my last term at Balliol, I became President of the Oxford Union, and Shirley — a friend and contemporary — wrote an extremely nice article about me in /sis, which, among other things, said that I read the Financial Times every morning at breakfast. Some- how this turned up in the newspaper cuttings on the desk of the then chairman of the FT, Lord Drogheda, who straight- away asked Roy Harrod to offer me an apprenticeship at the FT.' And that was the kick-start to the Rees-Mogg career in journalism — eight years at the FT, leading directly to the City editorship of the Sunday Times, and from there to the Times. Unfortunately Lord Rees-Mogg did not fully repay the favour with his 1981 leader. After all, he got the job he was after. Mrs Williams didn't.

This nine-year-old episode also shows that in the depths of the last recession, as monetarism really began to bite, Rees- Mogg had conceived a political hostility to Mrs Thatcher which is notably lacking in his more recent pronouncements in the Independent. Nowadays he — a quaintly ardent supporter of the restoration of the Gold Standard — would rather the Gov- ernment was more deflationary in its eco- nomic policies. In the language of the investment adviser — and under one of his many hats he is one — Lord Rees-Mogg seemed to be recommending selling Thatchers when they were at the bottom, and has since been buying all the way up. Perhaps this is just the establishment figure in William Rees-Mogg. The estab- lishment, after all, fears more than any- thing else blood on the streets and the subsequent dispossession it would have to endure. And in 1981 that did seem a distinct possibility. So I asked, 'Do you consider yourself a member of the estab- lishment, and if you do, is it through breeding, or by the sweat of your brow?'

`The answer is yes, plainly I am a member of the establishment, and it is entirely the result of the career I have had. The establishment, in my opinion, is a sort of interconnecting informal group of peo- ple who have got to know each other as a result of doing jobs in the past, so when you deal together again later on some quite different issue you know what their atti- tudes are, what they are like. This group does form a very useful network of opin- ions, and does act as a very useful system of communication.'

I suggested that this was all very well for bureaucrats and industrialists, but that he had always been first and foremost a journalist, and for a journalist to become just a channel for that 'useful system of communication' was not at all a healthy or desirable thing.

'That's perfectly true, and I think it would be disastrous if all journalists or a majority of them got into the situation that I am now in. That doesn't mean that I shouldn't be in it or that no journalist ought to be in it.'

But to be a member of the establishment suggests a certain cast of mind, one which Is largely innocent of true originality of thought, which simply embraces the con- ventional wisdom of the time, however absurd. So, I asked William Rees-Mogg (a devout Catholic), 'If you had been around at the time of the Spanish Inquisition would you have said, "This is the official wisdom; in God's name, these heretics must burn"?'

'I can't put myself in the position of . . er . . a Spaniard. I believe in complete religious toleration. But I think there is a seduction about power, and the establish- ment has a kind of power, and therefore one is exposed to an element of that seduction, and one can never say of oneself whether one would get something right or not.' So, translated, his answer was: maybe I would, maybe I wouldn't. In fact, the only honest answer.

Doubtless Lord Rees-Mogg was aware that I was trying to mock him. After all, this is something of which he has consider- able experience, having been ridiculed as the suede-shod establishment newspaper editor Elliot Fruit-Norton in Hare and Brenton's play Pravda, and received even rougher treatment at the hands of Simon Raven in his Alms for Oblivion, There, Rees-Mogg (a former High Sheriff of Somerset) is the model for the appalling Somerset Lloyd-James, a ruthlessly ambi- tious editor and blackmailing would-be politician whom Raven first has squirted on the head with sulphuric acid, before allowing him to commit suicide.

I had to ask, 'Were these portrayals in any way accurate?'

'I did see Pravda actually. I invited Rupert Murdoch [the model for the mega- lomaniac central character, colonial mil- lionaire Lambert Le Roux] to come along with me, but he wasn't free, unfortunately. I was portrayed as a very nice shrewd old gent. Bill Deedes, in fact, not me at all. But the people who wrote Pravda didn't know me. Simon Raven — a contemporary of mine at Charterhouse — saw much more clearly, he had a genuine view of the dark side of my character. Everybody has a dark side to their character. If you portray somebody in terms of what Jung called the shadow side you get a not very sympathetic character.'

`But Simon Raven can't have liked you very much?'

`To kill me off? Oh, I don't know.' Lord Rees-Mogg has a lack of rancour bordering on the saintly. But vanity? That is another matter.

`Did you feel that even if you were being satirised by these writers, you were at least of account enough to be worth traducing, and that that was pleasing?'

'Yes. It does me no harm. I like to be in a play, yes.' Doubtless Lord Rees-Mogg would have been still happier if the play could have been put on at the Albert Hall.

`Fancy a swim?'

Previous page

Previous page