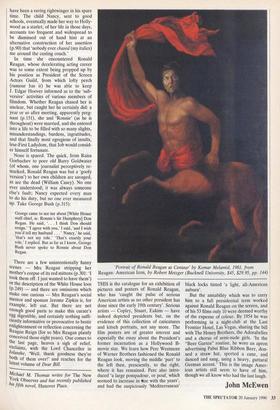

The Reagans in office and in art

Michael M. Thomas

MY TURN: THE MEMOIRS OF NANCY REAGAN by Nancy Reagan with William Novak

Weidenfeld & Nicolson,115.95, pp-384

With this book, the propensity of the House of Weidenfeld for the memoirs of well-known women reaches its predictable nadir. Let it be said, however, that Mrs Reagan's memoirs, an extended kvetch of nearly 400 pages, at first exert a certain fascination. One reads the opening 50-odd pages in growing disbelief at the thickness of the woman's carapace of solipsism, for surely only that can account for her willing- ness to reveal herself in this fashion. This disbelief, however, soon gives way to exasperation as the Pelion of whine is heaped on the Ossa of finger-pointing.

Compelled, too, is a certain admiration for her collaborator William Novak, the best-known and best-paid of American celebrity ghost-writers. There seems little doubt that he has succeeded in capturing the woman's very self and voice. So specifi- cally narrow an awfulness can only be rooted in reality; were a novelist to present so dimensionally limited a character, he would be abused by critics for an abysmal failure of imagination.

This book has been trashed by every critic who has encountered it, and who am Ito disagree? On the other hand, it is a big bestseller in the United States, and Mrs Reagan and her husband remain among the American people's ten most admired figures. On the basis of this book, I can only say that he and she, and they, deserve each other.

One might, I suppose, praise it for its `honesty', since that is the only possible word for this kind of self-revelation. Sadly, however, what is honestly revealed is chilly, self-referential, and dauntingly pre- tentious — to the point of self-parody. Only such a person could retail with pride (p.160) the fact that she revealed to her adopted stepson the facts of his parentage, which some might say were none of her business.

Perhaps her bitterness is due to her fat little legs, so out of keeping with her compulsive need to be thin, or perhaps there is a Freudian explanation. At Nan- cy's birth, she and her mother, a stage- struck woman right out of Gypsy, were deserted by their father and husband, to whom the Almighty doubtless vouchsafed a presentiment of the woman the baby girl would become. Mother later married a prominent — in this haut-bourgeois Middle-Western culture, to be 'prominent' is the summit of virtue — who appears to have been a raving rightwinger in his spare time. The child Nancy, sent to good schools, eventually made her way to Holly- wood as a starlet; of her life in those days, accounts too frequent and widespread to be dismissed out of hand hint at an alternative construction of her assertion (p.90) that 'nobody ever chased (my italics) me around the casting couch.'

In time she encountered Ronald Reagan, whose decelerating acting career was to some extent being propped up by his position as President of the Screen Actors Guild, from which lofty perch (rumour has it) he was able to keep J. Edgar Hoover informed as to the 'sub- versive' activities of various members of filmdom. Whether Reagan chased her is unclear, but caught her he certainly did: a year or so after meeting, apparently preg- nant (p.151), she and 'Ronnie' (as he is throughout) were married, and she entered into a life to be filled with so many slights, misunderstandings, burdens, ingratitudes, and that finally most egregious of insults, lese-First Ladydom, that Job would consid- er himself fortunate.

None is spared. The quick, from Raisa Gorbachev to poor old Barry Goldwater (of whom, one journalist perceptively re- marked, Ronald Reagan was but a 'goofy version') to her own children are savaged, as are the dead (William Casey). No one ever understood; it was always someone else's fault; Nancy expected every man to do his duty, but no one ever measured up. Take George Bush (p.315): George came to see me about [White House staff chief, ie. Ronnie's Sir Humphrey] Don Regan. He said, `. . . I think Don should resign.' I agree with you,' I said, 'and I wish you'd tell my husband . . ."Nancy,' he said, `that's not my role.' That's exactly your role,' I replied. But as far as I know, George Bush never spoke to Ronnie about Don Regan.

There are a few unintentionally funny scenes — Mrs Reagan stripping her mother's corpse of its red mittens (p.301: 'I took them off. I just wanted to have them') or the description of the White House loos (p.249) — and there are omissions which make one curious — Mrs Reagan's social mentor and sponsor Jerome Zipkin is, for example, left out. But there are not enough good parts to make this curate's egg digestible, and certainly nothing suffi- ciently informative or provocative to bestir enlightenment or reflection concerning the Reagan Reign (for so Mrs Reagan plainly Conceived those eight years). One comes to the last page, heaves a sigh of relief, exclaims, with the Lord Chancellor in lolanthe, 'Well, thank goodness they're both of them over!' and reaches for the latest volume of Dear Bill.

Michael M. Thomas writes for The New York Observer and has recently published his fifth novel, Hanover Place.

Previous page

Previous page