RUSSIA'S WINTER OF SABOTAGE

shortages are being manipulated to prop up the Soviet system

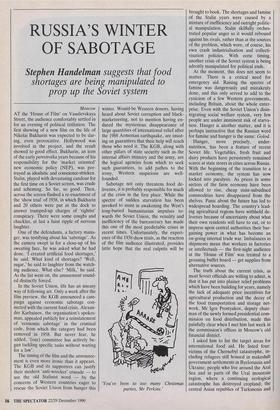

Moscow AT the 'House of Film' on Vassilevskaya Street, the audience comfortably settled in for an evening of political titillation. The first showing of a new film on the life of Nikolai Bukharin was expected to be dar- ing, even provocative. Hollywood was involved in the project, and the result showed to good effect. Bukharin, an icon of the early perestroika years because of his responsibility for the 'market oriented' new economic policy (NEP), was por- trayed as idealistic and conscience-stricken. Stalin, played with devastating candour for the first time on a Soviet screen, was crude and scheming. So far, so good. Then, across the screen flashed a re-enactment of the 'show trial' of 1938, in which Bukharin and 20 others were put in the dock to answer trumped-up charges of 'rightist' conspiracy. There were some coughs and chuckles, at last a faint ripple of nervous laughter.

One of the defendants, a factory mana- ger, was testifying about his 'sabotage'. As the camera swept in for a close-up of his sweating face, he was asked what he had done. 'I created artificial food shortages,' he said. What kind of shortages? 'Well, sugar,' he said to laughter from the watch- ing audience. What else? 'Milk,' he said. As the list went on, the amusement sound- ed distinctly forced.

In the Soviet Union, life has an uneasy way of following art. Only a week after the film preview, the KGB announced a cam- paign against economic sabotage con- nected with the current food crisis. Alexan- der Karbainov, the organisation's spokes- man, appealed publicly for a reinstatement of 'economic sabotage' in the criminal code, from which the category had been removed in 1958. But never fear, he added, '(our) committee has actively be- gun tackling specific tasks without waiting for a law'.

The timing of the film and the announce- ment is even more ironic than it appears. The KGB and its supporters can justify their modern 'anti-wrecker' crusade — to use the old Stalinist word — by the concerns of Western countries eager to rescue the Soviet Union from hunger this winter. Would-be Western donors, having heard about Soviet corruption and black- marketeering, not to mention having en- dured the mysterious disappearance of large quantities of international relief after the 1988 Armenian earthquake, are insist- ing on guarantees that their help will reach those who need it. The KGB, along with other pillars of state security such as. the internal affairs tninistry and the army, are the logical agencies from which to seek such guarantees, to add pathos to the irony, Western suspicions are well- founded.

Sabotage not only threatens food de- liveries, it is probably responsible for much of the crisis in the first place. While the spectre of sudden starvation has been invoked to assist in awakening the West's long-buried humanitarian impulses to- wards the Soviet Union, the venality and inefficiency of the bureaucracy has made this one of the most predictable crises in recent times. Unfortunately, the experi- ence of the 1938 show trials, as the reaction of the film audience illustrated, provides little hope that the real culprits will be `You've been to too many Christmas parties, Mr Perkins.' brought to book. The shortages and famine of the Stalin years were caused by a mixture of inefficiency and outright politic- al manipulation. Stalin skilfully orches- trated popular anger so it would rebound against his rivals, rather than at the sources of the problem, which were, of course, his own crash industrialisation and collecti- visation policies. With eerie timing, another crisis of the Soviet system is being adroitly manipulated for political ends.

At the moment, this does not seem to matter. There is a critical need for emergency aid. Raising the spectre of famine was dangerously and mistakenly done, and this only served to add to the cynicism of a few Western governments, including Britain, about the whole enter- prise. Even with the Soviet Union's disin- tegrating social welfare system, very few people are under imminent risk of starva- tion. Hunger is another matter, and it is perhaps instructive that the Russian word for famine and hunger is the same: Golod.

Hunger, more precisely, under- nutrition, has been a feature of recent Soviet life. Vegetables, fresh fruit and dairy products have persistently remained scarce at state stores in cities across Russia. With the beginning of the transition to a market economy, the system has now locked into paralysis. As prices in some sectors of the farm economy have been allowed to rise, cheap state-subsidised commodities have disappeared from the shelves. Panic about the future has led to widespread hoarding. The country's lead- ing agricultural regions have withheld de- liveries because of uncertainty about what their own residents will have to eat, or to impress upon central authorities their bar- gaining power in what has become an on-going internal trade war. Imbalances in shipments mean that workers in factories or intellectuals — the first-night audience at the 'House of Film' was treated to a groaning buffet board — get supplies from alternative sources.

The truth about the current crisis, as most Soviet officials are willing to admit, is that it has put into plainer relief problems which have been building for years, namely the lack of adequate price incentives for agricultural production and the decay of the food transportation and storage net- work. Mr Igor Prostyakov, deputy chair- man of the newly formed presidential com- mission on food distribution, made this painfully clear when I met him last week in the commission's offices in Moscow's old financial district.

I asked him to list the target areas for international food aid. He listed four: victims of the Chernobyl catastrophe, in- cluding refugees still housed in makeshift government settlements in Byelorussia and Ukraine; people who live around the Aral Sea and in parts of the Ural mountain region, where a continuing ecological catastrophe has destroyed cropland; the central Asian republics of Turkmenia and Tadjikistan who now have some of the world's highest levels of infant mortality; and finally, those on fixed incomes, includ- ing students, pensioners and invalids who are either unable to pay the new market prices or exist on the margins of Soviet welfare society. An important sub- category are the hundreds of thousands of refugees from ethnic violence who have swarmed into large urban centres such as Moscow and Leningrad. Each 'target population area', needless to say, has been increasingly marginalised by the inflation produced by the various economic experi- ments of the past few years. Mr Prostyakov estimated the total number of needy at some 81 million. 'When the economic system changed in Poland, living standards fell by one-third,' he said. 'If the same thing happened to those people, they would be nothing but skin and bones.'

The need for emergency, short-term relief, couched in those careful categories, is indisputable. But does the West have a role in relieving what is plainly a failure of the system? Here, the question becomes interesting. One could argue that all the reasons for the crisis mentioned above, as well as the consequences grimly sketched out by Mr Prostyakov, are inherent in the Soviet Union's inability or unwillingness to make real reforms, witness the grudging and poorly managed transition to the market.

But it does not completely explain why things happened to collapse so graphically in the sixth winter of perestroika. For that, one must return to the issue of sabotage. According to the Soviet ministry of trans- port, there were some 2,228 rail carriages filled with foodstuffs (including some fore- ign aid) waiting to be unloaded on 12 December. In Moscow alone, 378 carriages containing meat and dairy products were waiting untended. The accepted scapegoats for such a gross dereliction of responsibility are greedy speculators who are quietly siphoning off food to sell on the private market. A secondary explanation advanced with curious insistence is the `inefficiency' of the reform governments elected last spring in cities like Moscow and Leningrad and the 'scheming' of nationalists in rebellious republics who are allegedly using the situation to advance their own nefarious political aims.

Not, perhaps, coincidentally, these attacks resemble the charges advanced against the show trial defendants of the 1930s. The accusations against the demo- crats are particularly suspect. 'The fact that democrats are in power does not at all mean they wield any power,' the frustrated economist-mayor of Moscow, Mr Gavriil Popov, admitted recently. While the ineffi- ciency and confusion of new city adminis- trations is hard to deny, much of their helplessness is a result of the old-guard communist party bureaucracy which still remains in place and has refused to take orders from them. In some cases, their apparatchiki have actively been working to discredit their new bosses.

Consider, as exhibit number one, the following telegram unearthed recently by the Moscow News from the director of the main vegetable warehouse in Leningrad to the head of the Michurinsky state farm, Luzhsky district, in the Leningrad region: `We shall not accept delayed shipments of commissioned potatoes.' As Moscow News noted, the director sent the order even though he had received only 60 per cent of the potatoes needed for his customers. When the local district council found out about his quiet sabotage, and tried to dismiss him, his employees threatened to go on strike.

There is no way of knowing how wide- spread are such direct attempts at destabil- isation. But it is hard to avoid the conclu- sion that food shortages have conveniently helped to aggravate a backlash against the rampant democratisation of the past year and contributed to the new high profile of the security services. Even if such accusa- tions can never be completely docu- mented, they justify Western concerns that the crisis, unchecked, could plunge the Soviet Union into a period of civil chaos that would end with the recreation of an authoritarian regime.

Food aid, as much a political statement as a humanitarian one, serves as an impor- tant reinforcement (if it is properly chan- nelled) for those democrats battling against the growing popular hunger for a 'strong hand' at the top. Meanwhile, if some `saboteurs' are brought to trial, scepticism will be warranted. Mr Anatoly Matlin, an economist writing for the New Times, was one of several who have raised the ques- tion whether 'profiteering' was a consequ- ence of shortages rather than a contribut- ing cause. 'Who needs all the fuss around the shadow economy?' he wrote. 'Isn't it an attempt to shift the blame from the command-administrative system over to some other culprit, real or imaginary?' Soviet consumers with good historical memories would not have needed to see the Bukharin film to come up with their own answer.

Stephen Handelman is Moscow bureau chief of the Toronto Star.

Previous page

Previous page