A CLOUD OF WITNESSES

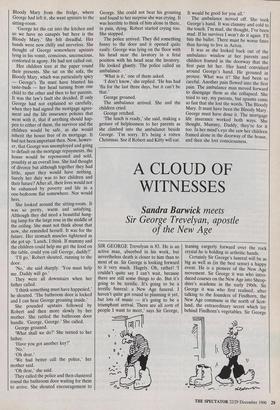

Sandra Barwick meets Sir George Trevelyan, apostle of the New Age

SIR GEORGE Trevelyan is 83. He is an active man, absorbed in his work, but nevertheless death is closer to him than to most of us. Sir George is looking forward to it very much. Hugely. Oh, rather! 'I couldn't quite say I can't wait, because there are still some things to do. But it's going to be terrific. It's going to be a terrific funeral: a New Age funeral. I haven't quite got round to planning it yet, but lots of music — it's going to be a triumphant arrival. There are all sorts of people I want to meet,' says Sir George, leaning eargerly forward over the rock crystal he is holding in arthritic hands.

Certainly Sir George's funeral will be as big as well as (in the best sense) a happy event. He is a pioneer of the New Age movement. Sir George it was who intro- duced courses on the New Age into Shrop- shire's academe in the early 1960s. Sir George it was who first realised, after talking to the founders of Findhom, the New Age commune in the north of Scot- land, the extraordinary secret which lay behind Findhorn's vegetables. Sir George it was who wrote, in the late Seventies, one of the great New Age guidebooks: A Vision of the Aquarian Age in which, amongst many other things, he warned of the dangers of polluting the great Being of Mother Earth. The doctrines of the New Age are fashionable. Though he has not achieved the reputation of his Uncle George, the historian, Sir George Treve- lyan none the less has made a distinctive mark, if not on Prince Philip, whom he taught at Gordonsroun.

He does not feel his work is yet done. These are exciting times, he believes: the New Age, which is one of a Second Coming, a spiritual outpouring of love into the world for anyone who cares to receive it, is already under way and will reach its climax within the next eighteen years. Sir George is not, he says, 'what you call a High Sensitive' but he has been told that this is not his final incarnation. 'I certainly expect to come back once more quite soon — I shall just go up for a wash and brush up and pop back again.'

His study, in a converted barn by an ancient church under the Cotswold Edge, not far from Bristol, reflects his life. He believes a ley line runs through it, a sort of spiritual electric cable. On the eastern window-sill of this upper room stands an ever-burning orange light, put there after a request from a higher plane. It is sur- rounded by a great heap of crystals, which Sir George uses in meditation. The room is filled with fine furniture of the post-Morris Cotswold School, some of it made by Sir George himself. A Cosmic Cross, with six ends, enclosed within a sphere and mounted on seven steps, rests on a table. Bar the television and video cassettes, Dr Faustus might have had such a room, or even Gandalf, the magician of what Sir George calls `Tolkien's great myth of the conflict of Light and Darkness'. Carved astrological signs adorn one bookcase: the room is crammed with books, and scat- tered here and there between William Morris prints are pictures of unicorns and angels.

Sir George is a firm believer in angels as well as in nature spirits, the Celtic 'little people' (who, he discovered in 1968, were responsible for the luxuriant growth and high quality of vegetables at Findhorn). Not only do we each have a Guardian Angel, 'allotted to us when we are born poor things — and we go through life without even saying thank you!' but a Higher Self. Both guide us through the great school that is life on earth, believes the baronet.

`All the time they are staging situations for your experience,' explained Sir George. let us say — a motor accident to slow you down. This is not determinism. Your Higher Self and your Angel stage the trial and when it comes to the moment of experience they step back and fold their wings and leave you to make a free decision. I'm on to a very important point here.'

On the other hand, if you are really in touch with your higher self you may feel a strong inclination to go and watch a sunset that very moment before the house crum- bles in an earthquake, and so escape. 'Or, if it is time, you may have a strong inclination to stay in the house and you will die,' said Sir George, with equal cheerful- ness.

It was at about this point that Lady Trevelyan called up the stairs and sug- gested tea. Lady Trevelyan is almost 90. She paints pictures of flowers and of her daughter and has had two pictures exhi- bited by the Royal Academy. Among her books, I saw nothing of the Higher Spir- itual sort, but a volume on Winston Chur- chill, and one on acts of bravery by animals.

Her expressed thoughts on death were also less ethereal than those of her hus- band: 'I rather think I hope I die before she does,' she said, gesturing towards her Border Collie, Lucy, to whom Sir George was administering material consolation in the way of illicit ginger biscuits.

Over tea Sir George recounted what he called an 'incident'. In his childhood he used, with is five brothers and sisters, to visit his grandfather, another Sir George, in Wallington Hall, Northumberland. They had to be on their best behaviour. Muted, whispering, the children crept about the great corridors and lofty rooms. A few years later his father, Sir Charles, inher- ited. All six children gathered in the central hall, with its Pre-Raphaelite fres- coes and vowed to banish the whispering: they let out one great joint shout which made the rafters quiver. Shortly afterwards their father received the surveyor's report on the state of the building. The cast iron vaulting in the central hall was in a dreadful state, it warned. 'It is now so fragile that a loud shout could be enough to

bring down the roof.'

Six guardian angels and six higher spirits had spared the Trevelyans and Wallington Hall. Sir George was preserved to be a pioneer of the New Age movement, and Wallington Hall is now in the care of the National Trust. Sir George's father, Minis- ter of Education under Ramsay MacDo- nald, gave it to the nation partly because of his socialist principles and partly, perhaps, because his son had turned, in his mid- thirties, from an agnostic, like his father into a passionate follower of Rudolf Stein- er's beliefs in a spirit world.

It seems a great shame to have deprived Wallington of its fourth, and highly colour- ful, baronet but there it is. Sir George is not regretful. His mind is on higher mat- ters. He is interested in the reports of those who have experienced death and returned. `You are released from the weight of matter, and you are lifted into light and lightness. Dying is a wonderful process. The descriptions are always exactly the same. They look down on themselves, and see the operating table, or the car crash, that sort of thing, and then they move at first through a funnel, opening into glo- rious light, and they are aware that the light is also a presence, who is sheer love, who receives them and they recognise who it is and what has happened — they meet their friends and their parents.'

An unhappier fate, he believes, awaits those who 'have rejected these ideas those who have lived for hate and material- ism and criticism of others — they will find themselves in surroundings which are a sort of counterpart of their thinking. They will find themselves in a sort of slum area, where the sun doesn't shine and unpleasant sorts of people are around them. And as they know death is the end, they think they're not dead. There are extraordinary accounts of people coming back again, making contact with those who can see unable to get home — lost, until they can be persuaded of what has happened, and they can let themselves lift.'

It is a gentle view of the after-life, and Sir George is, transparently, a soft-hearted and optimistic man. After tea he urged me to return to his study for one last word.

`He can't let people go,' said Lady Trevelyan. 'He loves talking. She's said she has to catch her train, George.'

But Sir George firmly led the way up. `Poor thing,' said Lady Trevelyan as I disappeared after him.

There is no dying without re-birth, he told me, once he had me settled back on the sofa. 'The next 30 years is the most important period in the whole of history. Do wake up to this. You're missing so much in opportunity if you don't wake up. The most exciting phenomenon is the rising tide of love in our brutal world.'

We walked back across the adjoining graveyard, the sun setting behind the church. 'Do look, stop, take it in!' cried Sir George.

Previous page

Previous page