BOOKS

The liberal tide

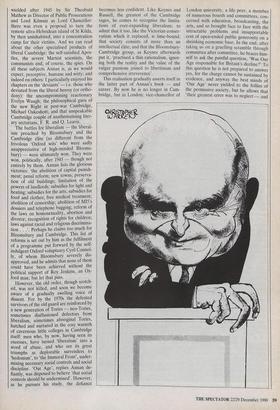

Hugh Trevor-Roper

OUR AGE: PORTRAIT OF A GENERATION by Noel Annan

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £20, pp.479

0 ur Age' — but whose age? Who are 'we'? To Noel Annan, now in his seventies, they are his contemporaries, but also rather more and rather less. More, because they include their mentors, mod- els, immediate precursors; less, because they are socially and culturally defined: they are, in general, those Englishmen who were born into the middle class, were educated at public schools and certain universities (especially Cambridge), and accepted, propagated and applied in life and politics certain common ideas. These ideas can be described as 'liberal': they were secular, anti-hierarchical, pluralist, tolerant, even (in the original sense of the word) libertine. As such, they were con- sciously opposed to the conservative ortho- doxy of the time — the inherited residue of Victorian social values. In due course 'Our Age' prevailed: the liberals of the pre-1914 era became the new establishment of the post-1945 era: an establishment which, having enjoyed its term of authority and achievement, now finds itself in its turn challenged and beleaguered by a new gen- eration professing new, or at least differ- ent, ideas — ideas which are markedly less liberal, less tolerant, less secular, and even, sometimes, though its hierarchies may be different, more hierarchical. This is a large canvas, and the picture painted on it here, the portrait of Our Age, is not only wide and various, extending into history and philosophy, literature and criticism, art and science, but also crowded with named persons in all these fields. Perhaps it would be easier to extract its message if it were less crowded: if the artist had not been tempted by his own abundant erudition to include such a procession of the thinkers and actors, dons, civil servants and committee-men, who have crossed his path, personally or intellectually, from Alcibiades, Althusser and Averroes through Homer and Habermas to Zeldin, Zuckerman and Zwerdling.

After admiring this impressive pageant, the less learned visitor to the gallery may feel the need to stand back a little in order to discover the form and unity of the work: to disentangle Harold Wilson (or was it James Callaghan?) from Themistocles, Evelyn Waugh from Pelagius, and to sort out the vivid but interlocking metaphors which enhance the colour of the work but sometimes obscure its meaning. For the unifying thesis in it is not simple. This is a complex And subtle work — indeed it becomes more complex, more subtle, as it progresses; which is no doubt the reason why ideologically committed (or indolent) reviewers have chosen rather to attack it impartially, from right and left — or to guy it, than to examine it.

Annan begins clearly enough as a Cam- bridge 'liberal', a disciple of the Blooms- bury group — he is, after all, the bio- grapher of its patriarch Leslie Stephen and a member of what Maurice Bowra (one of his few Oxford heroes, the robust patron of 'the Oxford wits') called 'the Immoral Front'. As such he naturally approves the crusade, preached so pertly by Lytton Strachey, to overturn the con- ventional Victorian values which, before 1939, were mechanically perpetuated in most public schools (though less in his own, the newly-founded Stowe of J. F. Roxburgh) and in the unreconstructed majority of Cambridge colleges, to which his own — King's, the King's of Keynes and Forster — was again an exception. So he rejoices in their battles — battles for revolutionary 'modernism' in literature and art, pacifism, sexual liberation — and is pleased that King's, in his time, was boycotted by right-thinking headmasters. He is entertaining on the ethos of the `gentleman', sedulously cultivated in the public schools and expressed by the popu- lar novelists of the time — 'Sapper' and John Buchan, so skilfully anatomised by Richard Usborne. He has excellent, sym- pathetic chapters on Bloomsbury, on the cult of homosexuality as a sign of defiance, and on the furious backlash against it, wielded after 1945 by Sir Theobald Mathew as Director of Public Prosecutions and Lord Kilmuir as Lord Chancellor: there was even a proposal to turn the remote ultra-Hebridean island of St Kilda, by then uninhabited, into a concentration camp for their victims. And we can read about the other specialised products of liberal Cambridge: the self-satisfied Apos- tles, the severe Marxist scientists, the communists and, of course, the spies. On all these subjects Annan is, as we would expect, perceptive, humane and witty; and indeed on others: I particularly enjoyed his chapters on the 'deviants' — i.e. those who deviated from the liberal heresy (or ortho- doxy): the uncompromising reactionary Evelyn Waugh; the philosophical guru of the new Right in post-war Cambridge, Michael Oakeshott; and that unspeakable Cambridge couple of anathematising liter- ary sectarians, F. R. and Q. Leavis.

The battles for liberalism — the liberal- ism preached by Bloomsbury and the Cambridge elite (so different from the frivolous 'Oxford wits' who were sadly unappreciative of high-minded Blooms- bury) — were ultimately won. They were won, politically, after 1945 — though not entirely by them. Annan lists the glorious victories: 'the abolition of capital punish- ment; penal reform; new towns; preserva- tion of old buildings; limitation of the powers of landlords; subsidies for light and heating; subsidies for the arts; subsidies for food and clothes; free medical treatment; abolition of censorship; abolition of MI5's dossiers and telephone bugging; reform of the laws on homosexuality, abortion and divorce; recognition of rights for children; laws against racial and religious discrimina- tion . . .'. Perhaps he claims too much for Bloomsbury and Cambridge. This list of reforms is set out by him as the fulfilment of a programme put forward by the self- indulgent Oxford voluptuary Cyril Connol- ly, of whom Bloomsbury severely dis- approved, and he admits that none of them could have been achieved without the political support of Roy Jenkins, an Ox- ford man; but let that pass. However, the old order, though scotch- ed, was not killed, and soon we become aware of a gradually swelling voice of dissent. For by the 1970s the defeated survivors of the old guard are reinforced by a new generation of Tories — neo-Tories, sometimes disillusioned defectors from liberalism, sometimes aboriginal Tories, hatched and nurtured in the cosy warmth of cavernous little colleges in Cambridge itself: men who, by now, having seen its excesses, have turned 'liberalism' into a word of abuse, and who see its great triumphs as deplorable surrenders to `hedonism', to 'the Immoral Front', under- mining necessary social controls and social discipline. 'Our Age', replies Annan de- fiantly, was disposed to believe 'that social controls should be undermined'. However, as he pursues his study, the defiance becomes less confident. Like Keynes and Russell, the greatest of the Cambridge sages, he comes to recognise the limita- tions of ever-expanding liberalism; to admit that it too, like the Victorian conser- vatism which it replaced, is time-bound; that society consists of more than an intellectual elite; and that the Bloomsbury- Cambridge group, as Keynes afterwards put it, 'practised a thin rationalism, ignor- ing both the reality and the value of the vulgar passions joined to libertinism and comprehensive irreverence'.

This realisation gradually asserts itself in the latter part of Annan's book — and career. By now he is no longer in Cam- bridge, but in London: vice-chancellor of London university, a life peer, a member of numerous boards and committees, con- cerned with education, broadcasting, the arts, and so brought face to face with the intractable problems and insupportable cost of open-ended public generosity on a shrinking economic base. In the end, after taking us on a gruelling scramble through committee after committee, he braces him- self to ask the painful question, 'Was Our Age responsible for Britain's decline?' To this question he is not prepared to answer yes, for the charge cannot be sustained by evidence, and anyway the best minds of `Our Age' never yielded to the follies of the permissive society, but he allows that `their greatest error was to neglect — and some even to despise — the need for their country to become more efficient, more productive in business and industry; and their greatest failure to persuade organised labour to join in that enterprise'.

Hence their eclipse and the triumph of Thatcherism, that ruthless, philistine, cost- cutting philosophy which is, in so many ways, a direct affront to all their cultural values and yet to which Annan, incorrigi- ble in his independence of spirit, pays the tribute of a wonderfully fair and balanced judgment. As for the future — but who can ever predict the future? 'Perhaps the re- forms "Our Age" had made in extending the liberties of the individual might last for a while. Perhaps not: who, in the time of the Regency, would have forecast the change in public morality that swept Eng- land during Victoria's reign?' So perhaps, as G. M. Young, who also wrote The Portrait of an Age — the Victorian age said to Robert Byron, when returning his copy of Lytton Strachey's Eminent Victo- rians, 'we are in for a bad time'.

This is an impressive book which few other men are qualified to write: impress- ive in intellectual range, in depth, and in judgment. If it is, as I have suggested, somewhat crowded, it is with rich matter, thoughtfully considered and elegantly ex- pressed. In it we hear the voice of that true liberalism which exasperates, and I hope will survive, the bigots on both sides.

Previous page

Previous page