Lucky quirks among the Romanesque

Peter Levi

THE VILLEIN'S BIBLE by Brian Young

Barrie & Jenkins, £19.99, pp.152

Ihave often wondered what the poor and illiterate made of the Bible. To judge from late mediaeval manuscripts of the Book of Revelation decorated with a Christlike hero something like Francis of Assisi, they thought it was about a magical revolution. Villon's mother saw only the damned and the blessed on the walls of her parish church, and prayed to be on the one side, not the other. The stone sculpture that can properly be called Romanesque narrows the vast field, but it is still ex- tremely wild. Who killed Cain when Cain had killed Abel? The Rabbis said Lamech, several generations his junior: a Lamech who was blind and mistook Cain for a wild beast, which he shot. Other Rabbis said his hand was guided by Tubal-Cain. The cu- rious scene occurs in stone at Modena, but who can tell now whether the peasants knew what it meant? Did they all know that the story of Cain and Abel meant you should pay your tithes? Did any of them recognise Eve suckling Cain on the door at Hildesheim? Or was sculpture a mystery, was the secrecy of its meaning part of its meaning? Some of the queerest stories are not in the Bible or in Christian doctrine at all. They attached themselves like shellfish to the church, embodied themselves in the arts, persisted, recurred, disguised them- selves. Many years ago I intended to publish in the Journal of Theological Stu- dies a Life of the Virgin, which was still sprouting new variations and episodes in the 17th century. Mediaeval narrative sculpture is as chaotic as it is admirable, like Greek vase painting. If you go further and let in the secular and allegorical decoration of the outside of churches, then mythology proliferates like orchids in a Brazilian forest. But let us assume that the Romanesque on the outer walls is merely the grotesque, not to be remembered once we get inside the church. The outer ring of the doorway at Barfreston church, on which this book tactfully neglects to corn- ment, though it is illustrated, is a case in point. It looks like an astrological allegory, but these illustrations are severely res- tricted to narrative and more or less Biblical stone-carving. The result is, I must say, utterly charming.

This book is the ideal Christmas present; it is often moving, it feeds curiosity and nourishes the wish to travel. It is like a party where one meets old friends long forgotten and makes the acquaintance of a few new ones. The text is sensible and interesting. For Sir Brian Young it must represent a lifetime's passion, and I hope he is now taking part in Professor Zar- niecki's survey of Romanesque stonework in England. He seems to have concen- trated on certain areas, so that his maps show surprising blanks: nothing south of Arezzo and north of Benevento, and in all Sicily only Monreale, between the Loire and the Seine only Dreux north of Veze- lay, and no Ireland, no England north of Uppingham and Much Wenlock. Yet the author has a classic taste, and what he does admit imposes a definition of Romanesque sculpture which it would be a pleasure to defend.

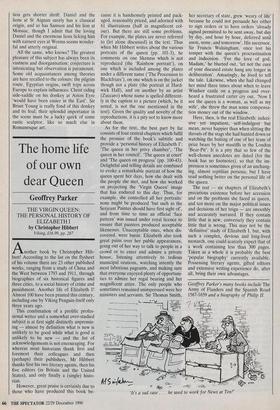

The carvers worked with a vivid glee, and an economy of conception which makes their figures extremely energetic. The same convention of curved lines does for water or clouds or even a blanket in which the three kings snuggle up like children, wearing their crowns like night- caps and brooded over by a huge angel like a Christmas goose. Almost no lines are perfectly straight, and Giselbertus of Au- tun is the most exciting artist, as one had always suspected. The Armenian influence is acknowledged and to a large extent documented, but the Greco-Roman tradi- Head of Christ in the monastery at S. Juan de las Abadesas, northern Spain tion gets shorter shrift. Daniel and the lions at St Aignan surely has a classical origin, and so has Samson and his lion at Moissac, though I admit that the loving Daniel and the enormous lions licking him with earnest eyes at Worms seems wonder- ful and utterly original.

All the same, who knows? The greatest pleasure of this subject has always been its vastness and disorganisation: conjecture is intoxicating but observation is paramount. Some old acquaintances among theories are here recalled to the colours: the pilgrim route, Egyptian origins, swift trips across Europe to explain influences: Christ riding side-saddle on his donkey at Aston Eyre `would have been easier in the East'. Sir Brian Young is really fond of this donkey and its foal; their splendid importance in the scene must be a lucky quirk of some rustic sculptor, like so much else in Romanesque art.

Previous page

Previous page