Exhibitions 2

Ben Nicholson (Tate Gallery, till 9 January)

Elegant modernist

Giles Auty

ith the exception of Naum Gabo, Ben Nicholson (1894-1982) was the only major figure of post-war art in St Ives I did not meet. At the time of his final departure from Cornwall in 1958, Nicholson's reputa- tion had probably reached its zenith. Some considered him then to be the most impor- tant British artist of this century. However, years of exile in Switzerland until his death in London in 1982 have probably not helped Nicholson's subsequent standing. Interest had revived in the meantime in other British artists such as Walter Sickert, Stanley Spencer and David Bomberg, while the careers of Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud continued to flourish after Nichol- son's death.

The present exhibition of over 130 works at the Tate Gallery helps us reassess Ben Nicholson's merits and national and inter- national importance. The show is timely, interesting and well put together, principal- ly by Jeremy Lewison, deputy keeper of the Modern Collection at the Tate Gallery. It pursues a chronology spanning 60 years from 1919 to 1979. It should be said here that the early work does not, in contrast to the cases of such artists as Stanley Spencer and Augustus John, suggest an especially important talent in the making. A good deal of it is awkward and indecisive; where direct comparisons can be made with com- parable contemporary productions by Nicholson's first wife Winifred or by his short-lived friend Christopher Wood these seldom favour Nicholson. The artist was in his late thirties by the time he was fully into his stride and he never acquired the beauti- ful fluency and certainty with a paintbrush so characteristic of his painter father, Sir William Nicholson. Ben Nicholson's art was essentially reliant on line and a precise placement of flattened shapes rather than modelling or fullness of form; in those for- mer lay its slightly astringent modernism. Clearly it was in part for his contribution to the development of modernism in Britain that Nicholson was esteemed so highly. Back in 1958 a simplistic view of the efficacy and benefits of everything modern prevailed in Western society not just in relation to art but most aspects of living. To cite just one example, prior to the sup- posedly wonderful, progressive decade of the Sixties, drugs were not a social problem in Britain. Today, so a senior police officer tells me, 70 to 80 per cent of all crimes committed in certain areas are drugs- related. Many authorities believe that the resultant social evils are incurable. Similar- ly unrestrained and unintelligent forms of radical behaviour in art have left anarchy and chaos in their wake. I fear this makes it Impossible for me to regard the condition of radicalism or modernism in art as any kind of automatic virtue in itself.

In art, as in every other field, some changes may be for the better while others will be just as surely for the worse. An extraordinary number even of the most eminent figures of the art world seem quite unable to grasp this most elementary of Principles and speak instead in a puzzled way about the way 'shifts of consciousness' affect art, as though these were uncontrol- lable or based simply on frivolous whims. In art, with any luck, we may come to our senses one day. When this happens reputa- tions based largely on artistic radicalism will tend to go down while those based on more durable criteria are likely to find the higher place which temporary fashions may

have denied them formerly.

Ben Nicholson was a gifted and accom- plished artist whose greatest talent was to grasp innovations made by others and reconstitute these in a refined and individ- ualistic manner. Cubism presented him with a first framework and geometrical abstraction a second; he had no hand in inventing either, yet found useful aids in both when creating a personal poetry. But the first major influence on his work was primitivism. There was also a clear effect arising from his first encounter with the St Ives naive artist Alfred Wallis in 1928.

Between then and 1932-33, when Nicholson's work took a major step for- ward in assurance, he had met Barbara Hepworth, who was married at the time to the sculptor John Skeaping. She was a strong professional influence but also began to become, some ten years after he married her in 1938, a serious professional rival, vying with him for honours at interna- tional exhibitions. Neither artist was short of self-esteem or ruthless ambition; to this extent both resembled the professional in- fighters of present-day art rather than their more idealistic contemporaries from an earlier time.

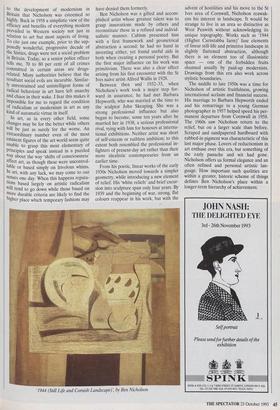

From his poetic, linear works of the early 1930s Nicholson moved towards a simpler geometry, while introducing a new element of relief. His 'white reliefs' and brief excur- sion into sculpture span only four years. By 1939 and the beginning of war, strong, flat colours reappear in his work, but with the `1944 (Still Life and Cornish Landscape); by Ben Nicholson

advent of hostilities and his move to the St Ives area of Cornwall, Nicholson reawak- ens his interest in landscape. It would be strange to live in an area so distinctive as West Penwith without acknowledging its unique topography. Works such as '1944 (Higher Carnstabba farm)' fuse elements of linear still-life and primitive landscape in slightly flattened abstraction, although there is an element too of illusionistic space — one of the forbidden fruits shunned usually by paid-up modernists. Drawings from this era also work across stylistic boundaries.

The middle to late 1950s was a time for Nicholson of artistic fruitfulness, growing international acclaim and financial success. His marriage to Barbara Hepworth ended and his remarriage to a young German photographer in 1957 helped speed his per- manent departure from Cornwall in 1958. The 1960s saw Nicholson return to the relief, but on a larger scale than before. Scraped and sandpapered hardboard with rubbed-in pigment was characteristic of this last major phase. Lovers of reductionism in art enthuse over this era, but something of the early panache and wit had gone. Nicholson offers us formal elegance and an often refined and personal artistic lan- guage. How important such qualities are within a greater, historic scheme of things defines Ben Nicholson's place within a longer-term hierarchy of achievement.

Previous page

Previous page