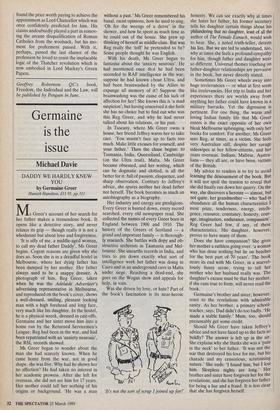

Lost leader in the fight for independence

Geoffrey Robertson

A PRICE TO HIGH by Peter Rawlinson

Weidenfeld, fI6, pp.264 etachment is a professional virtue in

D

a barrister, but a rare quality in the writer of political memoirs. Peter Rawlinson manifests it throughout most of this account of his high-flying counselling career, whether recalling how John Pro- fumo prevailed upon him to draft that fatal statement to the House of Commons or how Ruth Ellis, in the Old Bailey cells, begged him to make certain that she hanged. His professional dispassion slips only when remembering 'She Who Must Be Obeyed' — the Prime Minister who Signalled the end of his political career with the regal dismissal: `He can expect no Preferment from me!' For Margaret Thatcher, the author concludes, 'prefer- ment was what life had all become'.

yeter Rawlinson's preferment began With Harold Macmillan, who made him Solicitor-General in 1962 in time to partici- pate in the Vassall and Profumo affairs and to be privy to the granting of immunity to Anthony Blunt. He was Attorney-General throughout the Heath administration, pro- secuting the bombers of the Old Bailey and the kidnappers of Muriel McKay, negotiat- ing the Sunningdale agreement and the abortive settlement with Ian Smith, and controversially deciding that 'the public interest' — that greasy yardstick vouch- safed to the Law Officers alone — war- ranted suppression of the Sunday Times Thalidomide articles and the non- prosecution of PLO hijacker Leila Khalid. These momentous events are cautiously recounted, in the tight-lipped Tory tradi- tion of ministerial memoirs rather than the blabbermouth model associated with Crossman and Castle.

There are, nonetheless, occasional illu- minating details. Rawlinson seems to be- lieve that MI5 bungled the immunity from Prosecution offered to Blunt, and does not appear to have been informed of the similar immunity offered to Philby. His account of Profumo's behaviour is particu- larly unsympathetic, and he records with some pleasure how the Sunday Times, far from being the victim of oppressive gov- ernment censorship, actually colluded with him to bring the Thalidomide case to

court. (His arguments for suppressing criticism of Distillers now look threadbare, although they were accepted by the House of Lords and it took the European Court of Human Rights to produce a much-needed change in the law of contempt).

These memoirs raise important constitu- tional questions about the ambiguous role of the Attorney-General — a party politi- cian who is nevertheless the leader of the Bar and is expected by tradition to cast political allegiances aside when advising the Cabinet and determining whether the public interest justifies litigation. This alleged `independence' of the Attorney- General has always been vaunted as a check on government abuse of power, 'but Rawlinson argues that the Westland affair (and, it might be added, the Spycatcher saga) shows that 'what the modern admin- istration really wanted was tame "in- house" legal advisers, creatures of the Government more in the style of the retained family or company solicitor than of independent officers of the Crown'. It follows, as Rawlinson points out, that the Attorney-General should no longer be leader of the Bar nor responsible for deciding whether to prosecute in con- troversial cases. The Law Officers, and even the Lord Chancellor, will be `government legal eunuchs', ultimately awarded places in Cabinet, like other political careerists, as heads of a 'Ministry of Justice'.

Such consequences of the `Thatcher re-

volution' the author greets with distaste, although some would regard them as a long overdue recognition of the reality behind constitutional fictions. There is certainly a need for some check on the Government's power of preferment in the institutions of justice, and Rawlinson's somewhat belated advocacy of a Judicial Appointments Com- mission would be a useful start. The value of his analysis of the demise of the inde- pendence of the Law Officers is to provide further evidence of the need for a Bill of Rights to check the power of the executive. Lord Rawlinson may not yet be a signatory to `Charter 88', but his dire warnings of how independent law officers are being transformed into `tame legal eunuchs' pro- vides support, from an unexpected quar- ter, for a new constitutional settlement.

Distance has lent disenchantment to Lord Rawlinson's view of political life, 'a form of madness' in which the false friendships and the back-stabbings finally appeared `all very tedious, and rather comical'. CI began to realise that politi- cians never actually talk to anyone'.) His own courage was undeniable, and he made what many regarded as unnecessary per- sonal appearances to prosecute murderers and terrorists, but round-the-clock police protection took its toll on his children and his family life. It was this price which was, in the end, too high for a man who was by instinct a lawyer rather a politician.

Lord Rawlinson would, I suspect, have found the price worth paying to achieve the appointment as Lord Chancellor which was once confidently predicted for him. His claims undoubtedly played a part in remov- ing the arcane disqualification of Roman Catholics from the woolsack, but his mo- ment for preferment passed. With it, perhaps, passed the last chance of the profession he loved to resist the implacable logic of the Thatcher revolution which is now embodied in Lord Mackay's Green Papers.

Geoffrey Robertson QC's book, Freedom, the Individual and the Law, will be published by Penguin in June.

Previous page

Previous page