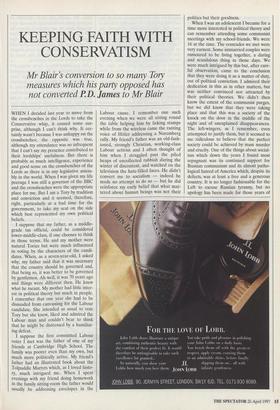

KEEPING FAITH WITH CONSERVATISM

Mr Blair's conversion to so many Tory measures which his party opposed has

not converted P. D. James to Mr Blair WHEN I decided last year to move from the crossbenches in the Lords to take the Conservative whip, it caused some sur- prise, although I can't think why. It cer- tainly wasn't because I was unhappy on the crossbenches; the opposite was true, although my attendance was so infrequent that I can't say my presence contributed to their lordships' usefulness. But there is probably as much intelligence, experience and good sense on the crossbenches of the Lords as there is in any legislative assem- bly in the world. When I was given my life peerage I was still a governor of the BBC and the crossbenches were the appropriate place for me. But I am a Tory by tradition and conviction and it seemed, therefore, right, particularly at a bad time for the government, to take my seat on the side which best represented my own political beliefs.

I suppose that my father, as a middle- grade tax official, could be considered lower-middle-class, if one chooses to think in those terms. He and my mother were natural Tories but were much influenced in voting by the characters of the candi- dates. When, as a seven-year-old, I asked why, my father said that it was necessary that the country should be governed and, that being so, it was better to be governed by gentlemen. Ah well, it was 70 years ago and things were different then. He knew what he meant. My mother had little inter- est in political theory but much in people. I remember that one year she had to be dissuaded from canvassing for the Labour candidate. She intended as usual to vote Tory but she knew, liked and admired the Labour man and couldn't bear to think that he might be distressed by a humiliat- ing defeat.

I suppose the first committed Labour voter I met was the father of one of my friends at Cambridge High School. The family was poorer even than my own, but much more politically active. My friend's father had an illustrated book about the Tolpuddle Martyrs which, as I loved histo- ry, much intrigued me. When I spent evenings with my friend doing homework in the family sitting-room the father would usually be addressing envelopes in the Labour cause. I remember one such evening when we were all sitting round the table helping him by licking stamps while from the wireless came the ranting voice of Hitler addressing a Nuremberg rally. My friend's father was an old-fash- ioned, strongly Christian, working-class Labour activist and I often thought of him when I struggled past the piled heaps of uncollected rubbish during the winter of discontent, and watched on the television the hate-filled faces. He didn't convert me to socialism — indeed he made no attempt to do so — but he did reinforce my early belief that what mat- tered about human beings was not their politics but their goodness.

When I was an adolescent I became for a time more interested in political theory and can remember attending some communist meetings with my school-friends. We were 16 at the time. The comrades we met were very earnest. Some unmarried couples were rumoured to be living together, a daring and scandalous thing in those days. We were much intrigued by this but, after care- ful observation, came to the conclusion that they were doing it as a matter of duty, out of political conviction. I admired their dedication in this as in other matters, but was neither convinced nor attracted by their political theories. We didn't then know the extent of the communist purges, but we did know that they were taking place and that this was a society of the knock on the door in the middle of the night and of unexplained disappearances. The left-wingers, as I remember, even attempted to justify them, but it seemed to me ridiculous to believe that the perfect society could be achieved by mass murder and cruelty. One of the things about social- ism which down the years I found most repugnant was its continued support for Russian communism and its almost patho- logical hatred of America which, despite its defects, was at least a free and a generous country. It is no longer fashionable for the Left to excuse Russian tyranny, but no apology has been made for those years of

active or tacit support.

Conservatism is, of course, a political philosophy, but for me it has always been less a set of rigid political theories than an instinctive way of looking at human beings and at the society which they comprise. Mrs Thatcher said that society does not exist and, although I think that this was an overstatement, I know what she meant. Society is comprised of human beings, indeed without them it couldn't exist, and unless human beings are happy, compas- sionate and prosperous, the society of which they are a part cannot be happy, compassionate and prosperous. Conser- vatism believes that people are more important than systems, and that what matters most is the freedom of the individ- ual under the law, whether we think in reli- gious terms of the individual human soul or of a unique human personality. Conser- vatism is patriotic but not jingoistic; the love of country runs deep in the party and comprises a love of the land itself, a respect for its institutions, its history and traditions and a reluctance to change unless change can be proved to be neces- sary. If change is not necessary, it may be necessary not to change. In the words of G.K. Chesterton, 'We grow conservative as we grow old, it is true. But we do not grow conservative because we find so many new things spurious; we grow conservative because we find so many old things gen- uine.'

Conservatism doesn't believe that poli- tics should be a substitute for religion and is wary of utopian ideals; the road to the promised land is too often paved with tyranny. Conservatives believe that people are both happier and better if they are allowed the freedom to direct their own lives, to decide how their money should be spent, to save and know that what they have built up will be bequeathed unplun- dered to their children, to decide how those children shall be educated. I can't myself see why it is acceptable to have two cars and a number of expensive holidays a year but not acceptable to spend the money on a private school for one's child. There have always been members of the Labour hierarchy who have chosen private or selective education. That is their right and I would do the same. But then I haven't consistently opposed the private sector or sought to deny the right of choice to others. The leadership of New Labour is placing importance on educa- tion, but if we look at the Labour-con- trolled authorities, they hardly present a reassuring picture of what happens when Labour is in control. And I don't myself think that some of the follies perpetrated in teacher-training colleges had been advocated by Tories. It's much the same with crime. Mr Blair is to be tough on crime and the causes of crime — the lat- ter, presumably, will be achieved by the statutory abolition of original sin — but I seem to remember that his party has con- sistently opposed measures designed to strengthen the criminal law.

And the mention of original sin is a reminder of a truth about our — or indeed any — society. If we all paid every pound of tax due from us, if we stopped the widespread abuse of the welfare system, if we took a more responsible attitude to health and stopped stealing from the health service, and if couples only had children when they were prepared to offer the child a loving and stable home and to undertake the sometimes sacrificial task of nurturing and caring for that child and bringing it to responsible adulthood, then we should have more than enough money to care for the old, the sick and the unfor- tunate with greater generosity than at pre- sent. Meanwhile we live in the real world, but perhaps bishops should remind us occasionally of these truths, although they are less agreeable to hear than that politi- cal parties or governments are always at fault. No doubt we shall continue to demand more social benefits from any gov- ernment than we are prepared to pay for, although the huge success of the Lottery suggests that the British have no objection to taxation or the redistribution of wealth provided it is voluntary. They have, howev- er, a keen appreciation of the level at which taxation becomes extortion.

As a Conservative I have never felt obliged to support all the measures enacted or proposed by a Tory government. Con- servatism is, like the Church of England, wide and tolerant enough to embrace a variety of beliefs beyond the central philos- ophy of the overriding importance of the individual. Freedom must include the free- dom to criticise, even to disapprove, and, as one might expect in 18 years, there are government measures which have dis- tressed Conservatives, among them the closing of Bart's hospital and the elevation of polytechnics into universities. Conser- vatism goes wrong, not when it becomes more conservative, but when it becomes less. I can see that it is expedient, and indeed necessary, for the Cabinet to speak with one mind, but the rest of us are free occasionally to disagree.

This is an extraordinary election. A great amount of time is being devoted to inessen- tials while the two most important issues, Europe and the constitution, have tended to be neglected. This is surprising, since these are the two issues on which there is a clear difference between the parties. They are also issues which will affect not only our own lives, but the lives of our grand- children and great-grandchildren, and which can change if not destroy the United Kingdom. I don't find it reprehensible that the Conservative party isn't united on Europe. The opposition isn't and neither is the country. We did, after all, vote for an economic community, not for a common currency or a European federation. During one of my promotion visits in Europe I was told by a senior politician in one EC coun- try, 'You in Britain have a northern Euro- pean attitude to treaties. We need Europe and it is vital for us to be part of it. We sign the treaties and if there is a clause that we don't like, then we don't keep it.' That may or may not be the truth, but a number of people in Britain suspect that it is.

Many of us are proud and happy to be European, and most of us agree that we must be part of Europe. However, I have yet to meet anyone who wishes to be part of a European federation. We have spent too much blood and treasure over too many years to retain our independence and sovereignty willingly to yield them, as it were, by the back door. And it would be easier for us to make up our minds on the question of a common currency if we knew more about the pros and cons. No doubt that will come if we have a referendum; in the meantime a policy of wait and see is probably the only sensible one, even if it doesn't supply an inspiring rallying call. It is folly for any government to give categor- ical assurance in advance of the facts. If I were an undecided or disenchanted Tory voter I would ask myself only one ques- tion: which of the two leaders has the greater negotiating skills and which will stand up the more strongly for our inter- ests in the Community?

The proposal for a Scottish parliament is one which fundamentally concerns not only Scotland but the whole of the Union, and how little information we are being given by New Labour. The West Lothian question won't go away. Will Mr Gordon Brown, for example, sit in the Scottish par- liament or in Westminster, or in both? If both, will he legislate for English educa- tion and health while the English no longer have a say in Scotland? If Scottish MPs no longer sit at Westminster, not only will this be the beginning of the break-up of the Union, but presumably the English parliament will more or less permanently have a Conservative majority. It is pro- posed that a Scottish parliament shall have the power to raise taxes. Mr Blair tells us that this will be subject to the overriding authority of himself in parliament at West- minster. But if a Scottish parliament can only raise taxes if Westminster agrees, then in effect it will have no tax-raising powers.

I am puzzled too about the proposal to reform the House of Lords. There is a sug- gestion that it should be a democratic chamber. A democratic chamber would necessarily be subject to some form of elective process, and an elected Lords would change its membership and its use fundamentally, and in my view very much for the worse. Would it be possible in an elected chamber to preserve that indepen- dence which is the chief virtue of the pre- sent House, a sturdy independence that is demonstrated not only on the crossbench- es, but on the government and opposition sides? And if a second chamber is to be elected, it will surely be entitled to the same authority as the House of Commons. Where then will the ultimate power lie? A party which has been in opposition for 18 years, free of the responsibilities and rigours of government, has surely had plenty of time to think out the details of its proposals for constitutional reform. Why then is Mr Blair so reticent about this and about so much else?

I am not a political activist; as a novelist my preoccupations and compulsions lie elsewhere; but I talk a great deal to the people I meet and there is no doubt that the country is deeply disenchanted with politics and with the political process. The early continued emphasis on sleaze and the sexual misdemeanours of a few mem- bers has harmed not one party but the whole of Parliament, since the British peo- ple are not so naive as to suppose that misconduct, sexual or otherwise, is con- fined only to one party, while the more sceptical have wondered what it is we're not supposed to be noticing while all this media outrage is going on. The young feel that their vote will make no difference anyway and that the parties are now so close that little real choice is being offered. Others have the feeling that real power no longer resides in Westminster and that, that being so, whether they vote or not is of little consequence. None of this is healthy for democracy. Of course it is agreeable for me to learn from Mr Blair that so many of my views and convictions over the past decades have been right, but I find the present conversion of the Labour party puzzling almost beyond belief. I accept that any political party is entitled to change its views — must change its views — to meet different needs and circum- stances, but has ever a party more thor- oughly and more quickly repudiated virtually every policy and principle for which it stood, and indeed on which it was founded?

Mr Blair is now advocating or accepting measures which for the last decade his party has consistently opposed and voted against. The Prevention of Terrorism Act is an example. Mr Blair, if in government, will continue to implement it. But if it was so wrong so recently, why has it suddenly become right? Surely the postponement of one horse race hasn't made all that differ- ence. The IRA has done far worse things. What the voters are now apparently being told by New Labour is this: 'Trust us. Noth- ing will change. We shall still carry out the Conservative policies, which you obviously prefer, but we shall carry them out more efficiently. And think what a nice change it will be for you all to see some new faces on the government front bench.' Well, that is a matter of opinion, and this does seem to be elevating Buggins's turn to a political prin- ciple. The trouble, of course, with stealing your opponents' clothes is that they fit much better on the original wearers and the sceptic might well suspect that your own clothes, carefully guarded, are still hid- den under the bushes at the riverside, ready to be put on again at the first conve- nient opportunity.

'I've got a job. Phil's working all hours God sends. We want money for a divorce.'

Previous page

Previous page